Didier Grumbach is one of the most discreet, yet powerful and prestigious figures in the world of fashion...

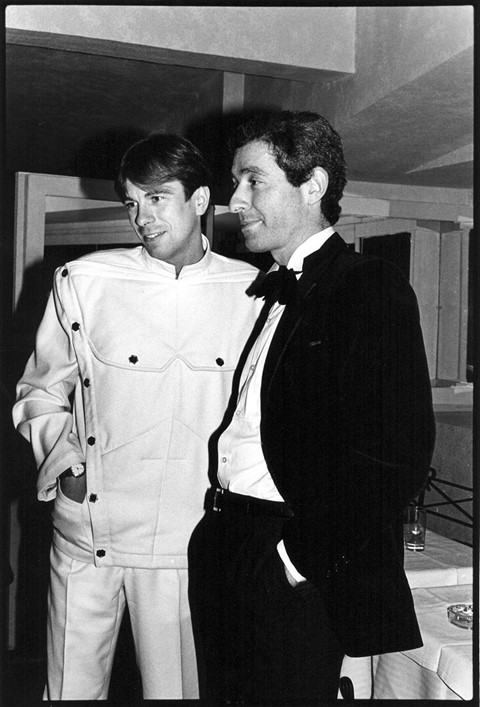

Didier Grumbach is one of the most discreet, yet powerful and prestigious figures in the world of fashion. In 1966, he co-founded Saint-Laurent Rive Gauche with Yves Saint-Laurent and Pierre Bergé. Between 1968 and 1973, he worked alongside Hubert de Givenchy in Givenchy Nouvelle Boutique. In 1971, Grumbach created the company Créateurs & Industriels, which aimed to bridge the gap between designers and the industry: in that context, he featured the first shows of designers such as Jean-Paul Gaultier, Issey Miyake and Jean-Charles de Castelbajac. He discovered Thierry Mugler’s talent very early on, and, in 1978, founded and became the chairman of the company that bears the designer’s name. He then served as chairman of Yves Saint Laurent, Inc. In 1985, he joined the staff of the Institut Français de la Mode, where he served as Director of Studies, and then as Dean of the Professorial Staff. In 1998, he was elected chairman of the Fédération Française de la Couture, du Prêt-à-Porter des Couturiers et des Créateurs de Mode, and of the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture. His book, Histoires de la Mode, first published in French in 1993, and reprinted with an afterword in 2008, has been translated in numerous languages, including Chinese, Portuguese and Romanian.

How would you connect fashion to elegance?

Elegance is related to self-control, whereas fashion is about interacting with other people. Elegance belongs to an individual, whereas fashion is constantly shifting and takes the risk of being provocative.

What is the role of history and art history in your conception of fashion?

There is no fashion when there is no liberty. And there is no fashion either when there is no economy. Fashion mirrors the changes in society. It was strong in France, when fashion was the privilege of the Royal Court. And then the Republic came and haute couture became a sort of oligarchy that diffused fashion to the world at large. Today, we are moving towards globalisation, and, although fashion may come from Japan, India, or China, its context still is, I think, very much focused on Paris.

Would you describe fashion as a language and a discourse, as Barthes did it?

It is a form of expression, a desire to interact, to communicate.

The word "intellectual" was coined in a time of great political distress. Does fashion have a political role? And in which way?

We cannot deny that the growing importance of fashion in China attests the country’s evolution towards democracy. Whatever we may say about China, a country I’ve been visiting for many years, even before the great liberation, the streets have changed, people have changed, the common behaviour has changed. Fashion does have a political role, because it’s a way for people to differentiate themselves, after a time when they all dressed the same and had no right whatsover to express themselves. They had to fight in order to get access to fashion, and that still is crucial today. We are very interested in fashion, obviously, but they’re passionate about it.

How would you relate the concept of fashion to the one of style?

When fashion designers have enough time to build their own répertoire, they create their own style, of which they become prisoners. When you have shaped a répertoire that is specifically your own, you cannot get out of it. We could not think of Alaïa designing a tartan coat, which could be mistaken for one of Lagerfeld’s. It’s the same as in painting: Renoir only paints Renoir’s... But in the context of an industry, it is complicated. Clearly, Mugler, Chanel, Saint Laurent created a style which they could not leave, and all long-lasting brands try to stay in a defined place in which they want the collection to stand.

"Today, designers are required to have a vision of the world that is specifically their own, so they need to be erudite, brilliant"

What does fashion have to do with intellectuality?

Fashion designers, especially when they launch their brand, are intellectuals. It is not possible anymore for a designer to be just a skilled craftsman. Today, designers are required to have a vision of the world that is specifically their own, so they need to be erudite, brilliant. Today, a fashion designer fulfills Poiret’s dream of being a guide, who announces everything, and not only fashion. Hedi Slimane, I think, represents a new type of fashion designer, who covers a very wide spectrum.

Since you have started working in fashion, the fashion world has considerably expanded. Which role plays the fashion world in defining fashion?

The fashion world is different in Paris and in New York. It has always existed, and is mostly constituted of what I call petits marquis, who talk about fashion with seemingly much knowledge and very little content. I am always amazed to see how certain people, most of the time journalists, are considered as prophets. American journalists have always played a major role in arbitrating between designers and keeping people secure. Today, it’s Anna Wintour, but yesterday it was Eugenia Sheppard, Diana Vreeland, John Fairchild. Sometimes, some of these prophets are truly passionate about their work and I must say that I particularly admire Suzy Menkes’ work. She sees every single fashion show, and, whenever there is a tiny move ahead, she gets it. It’s difficult, because you do not always get immediately the fact that a designer is immensely talented. When I first attended a Thierry Mugler fashion show, in 1976, he was not quite there yet, but I got it. Beyond any doubt. Today, I would not get it that way. The only thing that matters is for designer to discover new territories and bring costume history to move ahead.

Fashion, at its beginning, was based on the very selective character of haute couture. It is becoming more and more democratic. Does the process of democratisation actually change its meaning?

Couture was for a long time a huge industry. Until 1930, no less than 300,000 seamstresses worked in France. Ready-to-wear did not actually exist. And when Dior opened, after the Second World War, a woman’s couture suit cost roughly £700; today the same style would cost much more in ready-to-wear. Mrs. Carven, the same year, was selling 9000 pieces in couture per season. Women from the French province used to go to Paris to get nine, 10 pieces for their wardrobe. Of course, couture is not haute couture. But at the beginning, the couturiers who were accepted in the official calendar were traditionally called grands couturiers. And then, the category itself was fixed by a juridical decision from 1943. For 50 years, the quantitative criteria on which was granted the haute couture appellation were obsolete and unreachable. Since 2001 and the revision of these criteria, haute couture has been again what it was in the past, an observatory. Today, it constitutes the upper part of ready-to-wear. It provides designers from a new generation with the visibility their predecessors had when they entered the calendar – as Cristobal Balenciaga did in 1937. For a few years, a dozen of new brands, such as Yiqing Yin or Bouchra Jarrar, have started showing in Paris, and they started with couture, not ready-to-wear. Even though ready-to-wear pays for and supports haute couture. But when you think about it, the fact that Armani or Versace come here to show their couture collections is in itself quite an achievement.

In two weeks Donatien will be interviewing the artist and photographer Matthew Stone