In 1947 the Cooper Union Art School in New York began using the Rorschach ink blot test as part of its admissions process...

In 1947 the Cooper Union Art School in New York began using the Rorschach inkblot test as part of its admissions process. This was supposed to be a fairer way of judging creative potential than flipping through a portfolio, because the applicant's prior training, or lack of it, didn't get in the way. 'If Cooper Union is really bent on predicating its Art School's entrance exams on a pattern of response to inkblots,' wrote the New Yorker at the time, 'let it abandon its present activities for the early business of its Founder, the manufacture of glue, a substance every bit as efficient in gumming things up as psychological “projective” testing techniques.' These days, of course, it's perfectly normal to let someone into art school without actually bothering to check if they're any good at art – or at least I assume it must be, judging from every London degree show I've ever been to – but I wonder if Cooper Union Art School were aware that the Rorschach test's inventor was very nearly an art school kid himself. Nicknamed 'inkblot' as a child (honestly!) because he was always sketching, Herman Rorschach, the son of an art teacher, only went to medical school instead of art school after writing to the great German biologist Ernst Haeckel for advice. (Right: as if there was really any chance Haeckel was going to write back, 'No, science is boring, much better to spend two years taking a lot of ketamine and pretending to care about Joseph Beuys.')

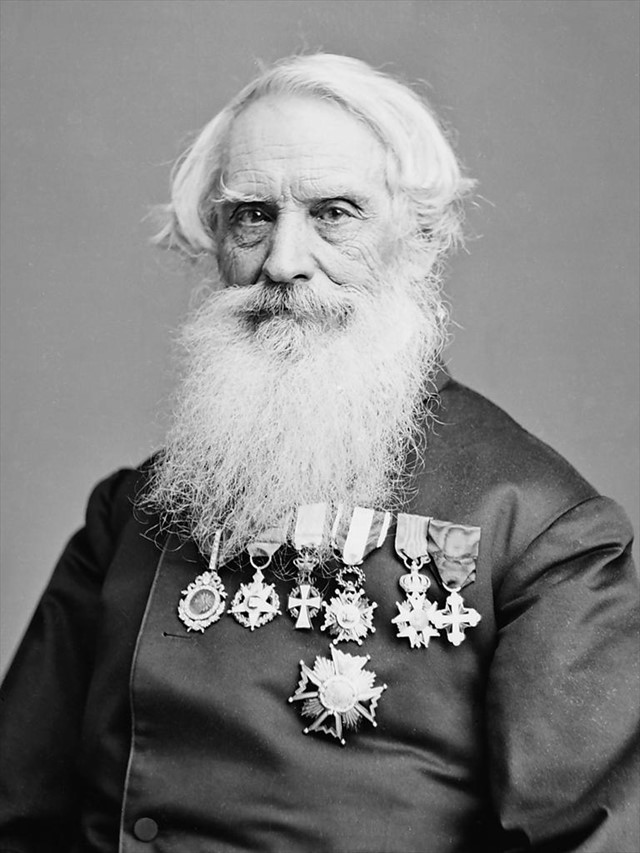

Rorschach died of peritonitis on the same date as Samuel Morse, the inventor of Morse code and one of the fathers of telegraphy. Morse, too, nearly devoted his life to art, and in fact he got a lot further than Rorschach – after several years working his way up through the ranks of the lucrative Washington portrait business, he was getting commissions from major military heroes like the Marquis de Lafayette. But in 1825, his wife Lucretia died suddenly at their home in Connecticut. By the time Morse found out she was ill, she was dead – and by the time he found out she was dead, it was too late to get back in time for the funeral. In a historical plot device that's almost too Hollywood to be true, this personal tragedy convinced him to develop a system that could transmit messages instantaneously, and he very quickly came up with Morse code. (He'd always been an amateur inventor, but not always such a sensible one: at one point he apparently tried to develop a marble-cutting device that could make unlimited exact copies of any sculpture. Pretty ambitious stuff for the age of Beethoven...)

Could you perform a Rorschach test with Morse code, where you send random blips to frantic telegraph operators and see what message they transcribe? Or send a telegram written in Rorschach blots, with mechanical squirt guns firing ink at a spool of paper? In any case, it's surely no coincidence that Morse and Rorschach both started off as artists. Like so many of the painters and sculptors to follow, these men asked, 'How far can I strip back my vocabulary if I still want to convey meaning?' An alphabet of only two letters, a symmetrical black splash that could be a moth or a face or a vagina: these sound like twentieth century experiments in minimalism. One wonders what sort of art they might have made if they hadn't turned away from their early aspirations, just as one wonders what the surrealist Max Ernst – who also died on today's date – might have invented if he hadn't started painting. Most of all, though, one wonders if any of these men would have passed the psychoanalytic entrance exams at the Cooper Union Art School.

Ned Beauman used to be Commissioning Editor at Another Man, writes often for Dazed & Confused and has contributed to the Guardian, the Financial Times, and many other publications. His debut novel Boxer, Beetle will be published by Sceptre in August 2010