There is much comment on the ups and downs of fashion’s turbulent relationship with the financial markets – when stock is up, so are hemlines. But this season’s long skirts, seen at Ann Demeulemeester and Yohji Yamamoto, reflect much more than just

There is much comment on the ups and downs of fashion’s turbulent relationship with the financial markets – when stock is up, so are hemlines. But this season’s long skirts, seen at Ann Demeulemeester and Yohji Yamamoto, reflect much more than just our current fiscal fiasco – they’re emblematic of a new age for fashion.

The long skirt is in the first instance a throwback to more austere times: women have kept their pins under wraps from the moment cavemen started getting twitchy about someone else checking out their wife’s ankles. They’re symbolic of reserve, formality, nostalgia, even repression.

After the elaborate volumes of skirts during the Elizabethan age, with the Regency and the short-lived Directoire period came a more streamlined silhouette, which blossomed among a small group of Parisian socialites towards the end of the 18th century. Thereafter, strict Victorian mores ensured another growth spurt in the span of skirts, some of which took up entire train carriages trundling along the newly invented railroads. Reform came only with a change of monarch and a change of underwear.

The fin de siècle corset shape was an S-bend, designed to promote the bust and derriere, and skirts subsequently cascaded over a bustle rather than sweeping out to the sides, heralding a narrowing of line. But this was soon abandoned with the invention of Paul Poiret’s “hobble skirt.” Creating a revolution in women’s wardrobes (despite the wearer’s movement being severely impeded), Poiret’s system of dressing focused on separates rather than entire ensembles. The skirt, worn with blouses or tunics, became a skirt in its own right, rendering the matching bodice obsolete.

During the 1920s hems rose in a nod to feminine empowerment and austerity measures, but they descended again in the Thirties, a decade known first for its decadence, then its dictators. Change came again with wartime rationing – there was simply not enough fabric for full-length creations. The next incarnation of the long skirt arrived in the Sixties, as a bohemian take on a nostalgic pastoral idyll. But this time it came with the vote, sex and drugs.

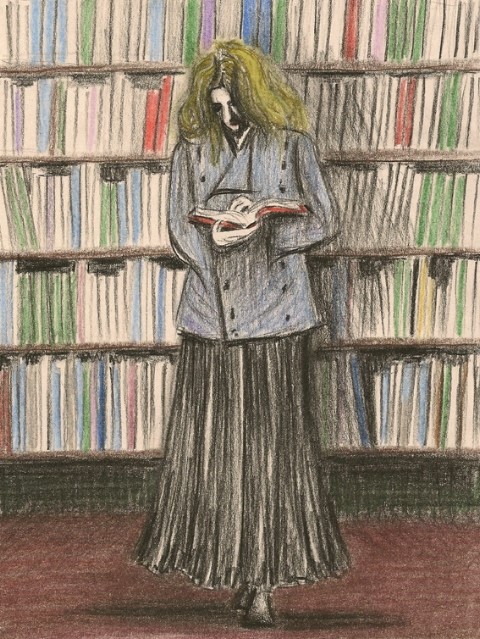

Since then, long skirts have become political. They’re a subculture unto themselves; wearers are intellectuals, goths, the Plymouth Brethren. They’re an oddity in a society full of bare thighs. When Yamamoto presented his collection’s long black skirts in the Eighties, against a backdrop of Thierry Mugler and Christian Lacroix’s trompe l’oeil mini-crinis and bird-of-paradise aesthetic, onlookers were shocked and assumed his take was one of negativity and cynicism. In fact, it was a purity of vision, and one that he has returned to for autumn 2010.

The long skirt may have associations with modern Puritans, but it isn’t a moral decision to wear one – not any more. It is symptomatic of a wish to remove oneself from the Nuts, Zoo and Heat magazine culture; to ask for attention by not displaying flesh; to question what is eye-catching or elegant or intriguing.

And so to the disbelief and dismay of the masses, long skirts swished, swirled and trailed through the autumn collections: some gothic, some romantic – all deadly serious.

Zoë Taylor has appeared in Le Gun, Bare Bones, Ambit and Dazed & Confused. She is currently working on her third graphic novella and an exhibition