With the ascendance of Michelle Obama as a modern-day style icon, it seems apt that the theme of this year’s annual Costume Institute extravaganza at the Metropolitan Museum in New York saw a return to its roots. American Woman: Fashioning a

With the ascendance of Michelle Obama as a modern-day style icon, it seems apt that the theme of this year’s annual Costume Institute extravaganza at the Metropolitan Museum in New York saw a return to its roots. American Woman: Fashioning a National Identity traces the evolution of style for the country’s female population from the period between 1890 to 1940, taking in the cosseted daughters of robber barons, through to the sporty, athletic Gibson Girl, and finally to the Hollywood siren that remains the prevailing ideal of glamour today. For its curator, Lancashire-born Andrew Bolton, it follows on from previous successes Superheroes: Fashion and Fantasy, and last year’s Model as Muse. Bolton worked for ten years at the Victoria & Albert Museum before transferring to the Costume Institute in 2001. He represents a new breed of fashion curator, with a more democratic approach to the form. In 2007, Bolton and Harold Koda put on Blog.Mode: Addressing Fashion, which predicted the rise of the blogger as a legitimate voice in fashion. Here, he talks to AnOther about the importance of accessible fashion and his work on American Woman.

Andrew Bolton: I’ve loved fashion ever since I can remember. I came of age in the early 80s when magazines like i-D and The Face got started. The images by Ray Petri of Buffalo epitomised the male fashion gaze for me. They seemed so hard and soft at the same time. It was very much focused on the male body and the idea of the fashionable male experience. As a kid I would also see fashion through music. One of my first music engagements was with punk. For me, punk was such a radical break from anything that went on before. It was so refreshing, it was really hard-edged, and it was all about deconstruction. It was a really exciting time to be in England.

I see the role of curator as really having evolved over the years. It’s about the promotion and appreciation of fashion as an art form. The shows I put on try to enhance that accessibility, but at the same time try to foster an appreciation of the conversation of fashion. The designers I gravitate towards are those like Galliano, McQueen and Westwood who tell stories through their fashions, who conceptualise fashion through the idea of narrative. I love designers that are raconteurs or myth-makers. I love this idea of fashion as fantasy.

I try to curate shows that have a relevance to what’s happening in contemporary culture. When I curated the Superheroes show, it was at the height of the superhero films like Iron Man and Dark Knight. Spider-Man was my favourite character as a kid and I felt that the superhero was a great metaphor for fashion as metamorphosis. The power of fashion lies in its power to transform identity. So I try to fit in ideas with the zeitgeist. Even when we put on Dangerous Liaisons, which was purely about the 18th century, we put a spin on it – sex basically! So we are always thinking of a theme that’s timeless or has a contemporary resonance.

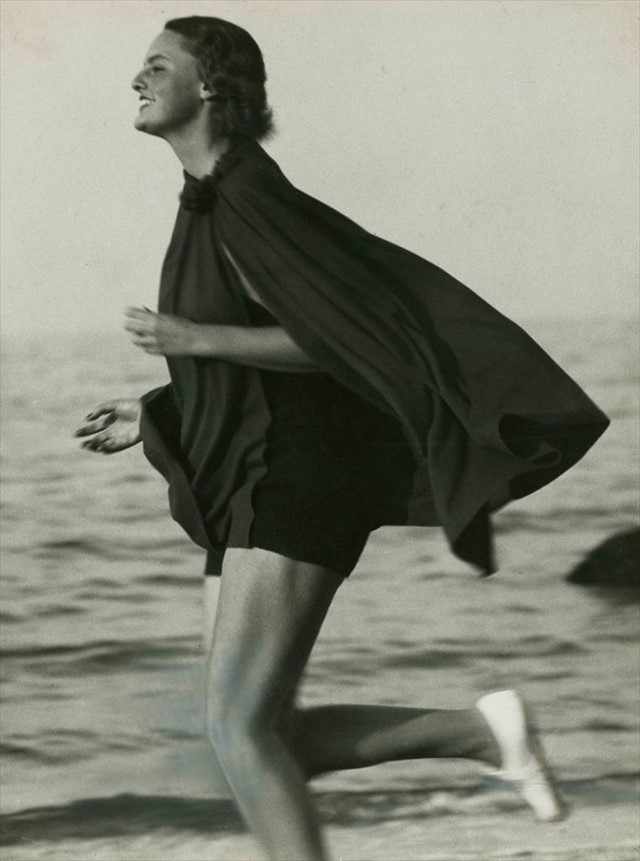

With American Woman we wanted to put together an exhibition celebrating the transfer in January 2009 of the Brooklyn Museum’s costume collection to the Met. I was thinking about American identity and wanted to approach the collection from a conceptual point of view. Diana Vreeland did an exhibition in 1975 called The American Women of Style, which included women like Millicent Rogers who had donated their clothes to the Brooklyn Museum. So originally I had wanted to do a sequel to that. Going through the collection in more depth, I felt that what was more visible than these individual identities were the archetypes of American identity that stood out, like the Gibson Girl, the flapper, the screen siren. With the growth of mass media in the late 19th century, the first archetype to be generated and perpetuated was the heiress, people like Consuelo Vanderbilt – they were the social celebrities of their day. They were associated with the gilded age of America. What I wanted to do was to show how the American woman became increasingly emancipated and how she felt more secure in her self-presentation, so that in the 1930s the fashion gaze had switched towards America and Hollywood, the screen siren. So it’s still a sequel to Miss Vreeland’s show, but a different take.