In AnOther Magazine A/W07, Siri Hustvedt and Fred Tomaselli met to discuss topics as far afield as psychosis and Grey's Anatomy

For the art special in AnOther's A/W07 issue, we introduced two non-native New Yorkers: wordsmith Siri Hustvedt and the master of dazzling, psychedelic art, Fred Tomaselli. In a conversation that considered indigenous art, Grey's Anatomy, the notion of beauty and giving up smoking, the pair traversed an intellectual landscape as varied and nuanced as one of Tomaselli's paintings. Here, we present an small extract.

Making patterns is human. Symmetrical patterns appear in every culture, from tribalism to capitalism. It’s an impulse – a physiological and universal one, I’m convinced – towards order. Making patterns or repetitions is what our minds do, and it’s the ground of all meaning. How does pattern function in your work? And to return to cosmologies, how is it related to ideas about the grand scheme of things?

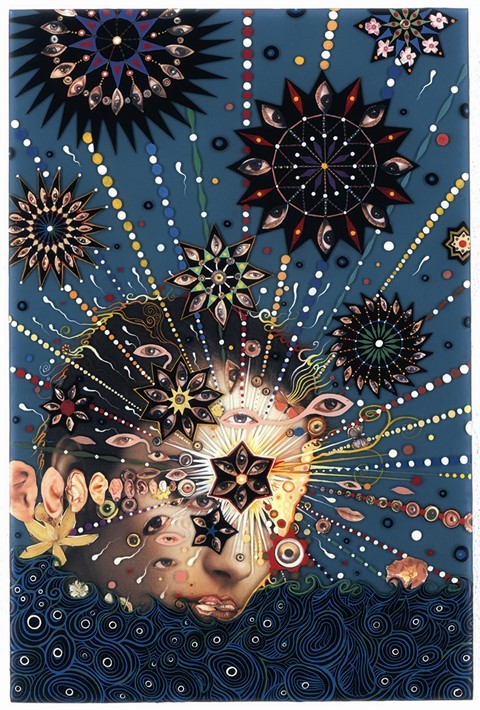

When I see the different indigenous art found throughout the world, I can’t help but notice their commonalities. I also can’t help being seduced by them. It’s almost as if these archaic patterns are encoded in our DNA. I’d like to think, that by using these archetypes, I can save my work from the passive-aggressive strategies that seem to define so much contemporary art. Pattern can be quite musical, almost trance-inducing and hypnotic. Hopefully, it can suck the viewer into the work long enough for some thinking to occur. Sort of like a pop song – melody first, lyrics second. It’s fine with me if the viewer wants to absorb the work on strictly formal terms. In my pictures, I may imbed pattern with personal and social content, but I’ve also come to believe that pattern is its own content.

I’m a great fan of Gray’s Anatomy. Sometimes, I examine bodies and elaborate renderings of organs. In some of your more recent works, you’ve included a number of fascinating human bodies – the poor fellow in Expecting to Fly, for example. In his transparent body, the viewer sees more body parts, representations of insects, birds, fruit, and flowers of various sizes, and a fairly large snake that is both phallic and mythological. How did the human body become part of your work?

The human body has been present in my work from the beginning. I always saw my shows as a sort of disassembled world that was weighted towards landscape and abstraction, with a sprinkling of one or two figures. I also made the occasional narrative picture whose stories were acted out by birds or bird armies. I guess I wanted to make things a little more overt, so a few years ago, I completed a body of work that was weighted more heavily towards the figure. A lot of that work dealt with death, oblivion, the grotesque and the sublime. I was watching my son growing up and getting stronger. Meanwhile, I had a health scare and my mother died and then there was the war in Iraq. I felt as if I was falling apart.

Collecting interests me because it fetishises category. It’s an urge born of the Enlightenment with its encyclopedias, museums and optimism that everything can be ordered and named. Contemporary popular culture, at least in the US, largely retains this faith. There’s a line in Jonathan Lethem’s story ‘The Collector’ in your book Monsters of Paradise: ‘Category errors nagged his psyche.’ In your art, I feel an intense tug-of-war between a love for the encyclopedic and an awareness of its failures. Teratology, the study of monstrosities, is a kind of oxymoron – the investigation of that which resists category. Can you talk about your sense of the monstrous?

I've referred to the charismatic madmen who try to define history, but we are also dealing with the monstrous in the realms of science and technology. It’s interesting that you bring up ‘category errors’ as they conjure a kind of monstrous hybridity. Category errors makes me think of genetically altered life forms, bad clones and franken-food. Hybridism is central to my work; in the materials I use, in the combination and clotting of those materials into different forms, and in the differing ideologies and pictorial traditions at play in the pictures. I also come at the work with a hybrid consciousness morphed by drugs and media. I don’t know how monstrous it all is, but category errors abound.

Your paintings are beautiful. I often wonder why we find some things beautiful and others not. Beauty is a mysterious business. For me, there is often something a little dangerous and alien about it. What does the idea of beauty mean to you?

I agree that true beauty is always a little strange. If it’s not strange enough, it’s merely pretty. If it’s too strange, it’s just alienating. Beauty is all about balance. I tend to like a little pathology with my beauty, and when it gets a little dangerous, beauty can become sublime. For me, beauty also lies in a conversation between the senses and the philosophical mind.

For the full article, and for all 25 issues in the AnOther Magazine archive, visit Exact Editions.