Born in West Berlin, Dennis Schoenberg grew up near Frankfurt, fascinated by film. With a desire to study the medium and faced with oversubscribed courses in his home country, in 1995 he moved to London...

Born in West Berlin, Dennis Schoenberg grew up near Frankfurt, fascinated by film. With a desire to study the medium and faced with oversubscribed courses in his home country, in 1995 he moved to London.

“At the same time, I was also interested in photography,” Schoenberg expands. Having picked up an MA in the subject from Westminster University, his formative years were spent assisting Rankin at Dazed & Confused and Steven Klein in New York before becoming Wolfgang Tillmans’ studio manager.

Convention rules that the apprentice adjusts to the practitioner’s ideology, yet Schoenberg became more and more himself with these experiences, a world away from the high-production drama you’d expect. “With Wolfgang, I wasn’t an assistant for photography at all – he doesn’t need one, he does it all himself. Yet that is when the real excitement came. I’m continually impressed by what he does; he doesn’t do anything he’s not comfortable with and never had aspirations of fame. He was interested in his art, his vision.”

It was Terry Jones, founder and director of i-D that gave the young German his first break. On being shown photocopies of Schoenberg’s pictures he was convinced immediately. “My work was pretty much what it is now, often with people I’d found as the subject,” Schoenberg declares. “I was trying to capture something within that person, just one image of them that describes what they’re about. It’s impossible, but that challenge is so captivating. They always felt really comfortable how I’d portrayed them.”

Schoenberg wasn’t working with stylists at the time, that came along later. “It was portrait-based, but always about fashion and style.”

A result of the climate in the 90s, his work became possible due to the integration of the aesthetic (and practices) of artists such as Nan Goldin and William Eggleston into fashion. “It was totally about realness,” Schoenberg says. “It was also subculture-based, much more than pop culture. The 60s, 80s was pop culture, and with the 90s that changed.”

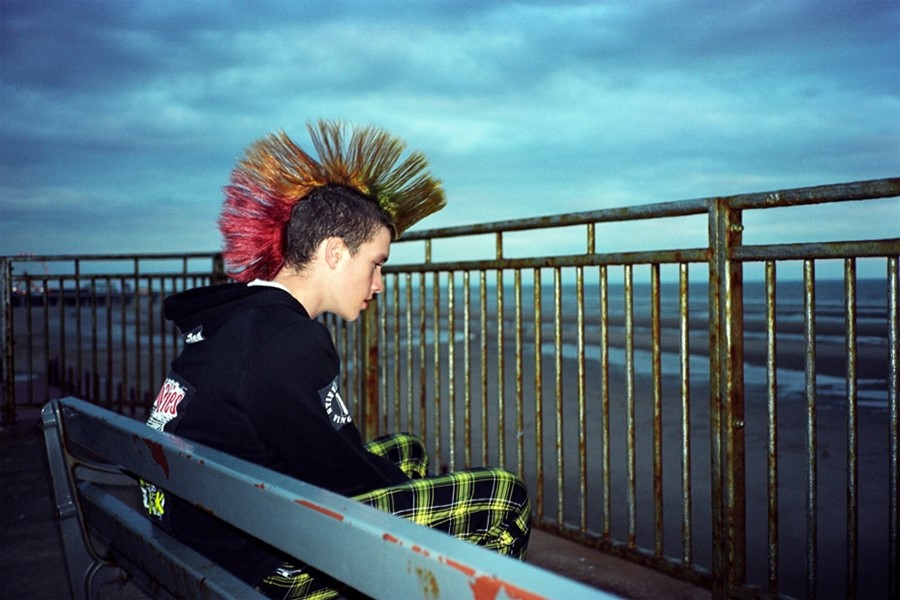

Schoenberg’s current punk and skinheads project goes back to a fascination with alternative music nurtured as a teenager. “My first gigs were punk concerts at 13 or 14. It was second-, third-generation punk – too late – but there was still the aesthetic. It was so powerful – the bands were either English or American and I didn’t know anything about the politics. That excited me.”

“No one was mentioning the 30th anniversary of punk in 2007, but it’s still so relevant within fashion, music and culture,” he adds.

Other than Helmut Lang, the universal reference for most contemporaries, Raf Simons and Hedi Slimane are the designers who best represent what Schoenberg is about. Bigger than clothes, their work reflects the way we live, our world and our emotional energy.

“Look at the book Redux by Raf Simons,” reflects Schoenberg. “That sums everything up.”