It’s an emphatic mark of the current social and economic divide that while one well-known supermarket names its value brand “No Frills”, Paris’s autumn/winter 2010 couture week was full of them...

It’s an emphatic mark of the current social and economic divide that while one well-known supermarket names its value brand “No Frills”, Paris’s autumn/winter 2010 couture week was full of them.

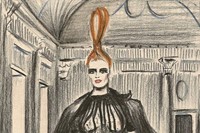

They frothed and foamed on bodices, sleeves, shift dresses and skirts all over the world’s most exclusive catwalks in collections that referenced every possible version of womanhood. From temptress to angelic, via prim and ladylike, to exotic birds of paradise: there’s a frill for every occasion.

Whether rough-hewn in leaf-like taffeta at Dior, where jagged layering not only adorned jackets but also seemed to create the very foundations of vast mille-feuille skirts, or gently fluid in organdie and tulle on baby-doll dresses at Valentino, frills in all their guises were emblematic of haute couture’s opulence and romanticism this season.

Defiantly thumbing its well-bred nose at ready-to-wear’s wholesale embracing of minimal, streamlined styles for autumn, couture – as always – has decided to play by different rules. Frills have never stood for real life and practicality – there’s a reason why they didn’t appear until the 15th century, when the leisured classes had properly evolved (and found others to do their dirty work), and it’s something to do with the frill’s unsuitability for manual labour, everyday grot and the rigours of working for one’s living.

But the archetypal working girl was referenced by Jean-Paul Gaultier (when isn't she?) with black lace bodices underscored by a preponderance of frilled black lace knickers – the ultimate in boudoir wear de luxe, and so capacious that it would take a full crinoline skirt over the top to avoid a VPL.

This is the thing with frills: they're not practical, and not meant for modern life. In the 18th and 19th centuries, women flaunted their status by the amount of frills they had; the more weighed down by frou-frou layering, the less of a burden one’s very existence was. And in the 80s, power suits and minimal tailoring were undercut by frills that were meant to signify naive shepherdess chic.

That same decade, the likes of Rei Kawakubo and Yohji Yamamoto employed the frill at its most deconstructed: ruffles that stopped halfway around the circumference of a coat, frills that looked like they had been dragged through hedges backwards. And so much the better. Hussein Chalayan and Viktor & Rolf have also explored the volume created by an excess of frills, making something normally so ephemeral and excessive become the integral and structural underpinning of a garment.

“There are different kinds of ruffles, you know,” Cristóbal Balenciaga told Hubert de Givenchy when they worked together in the 40s. “Some ruffles must be very, very elegant and light. You must make it become an intelligent ruffle.” Givenchy's heir Riccardo Tisci did just that this season, with notched and curlicued white lace ensembles, decorated by tiny, knife-edged ridges of frills placed at the cohesive points of a bodice, a sleeve, a skirt. They turned something naive into something new yet nostalgic – and that, one might point out, is what couture is all about.

Zoë Taylor has appeared in Le Gun, Bare Bones, Ambit and Dazed & Confused. She is currently working on her third graphic novella and an exhibition