Traditionally, autumn is the time for fashion to reveal what it has up its proverbial sleeve. But this season it didn't – because there were few sleeves to speak of. Designers eschewed the usual winter wardrobe staples of investment coats and

Traditionally, autumn is the time for fashion to reveal what it has up its proverbial sleeve. But this season it didn't – because there were few sleeves to speak of. Designers eschewed the usual winter wardrobe staples of investment coats and layered outerwear and opted for capes.

Whether warm and rug-ish as at Chloé, or downright ecclesiastical like Yves Saint Laurent’s, the preponderance of capes and cloaks on the catwalks revealed a general dissatisfaction with the usual modes of cold weather dressing.

But capes are no newcomers to the circuit. Since sartorialists realised the potential warmth that comes from swathing the body in a layer of fabric (that's the Romans and Anglo Saxons), capes have been a go-to for those who favour function over structured form. These somewhat old-school constructions left arms free for harvesting, duelling, carousing and praying.

Latterly though, capes have been seemingly simplistic, negating any need for the type of technical enhancements that plagued the likes of Balenciaga and Givenchy, who spent years, if not decades, agonising over the cut of a sleeve. The cape may not work for those who like to sling an It-bag over one shoulder (or indeed a rucksack over both), nor for sturdier types who favour the thrusting of hands into deep pockets, but they offer an opportunity for drapery that more tailored garb does not.

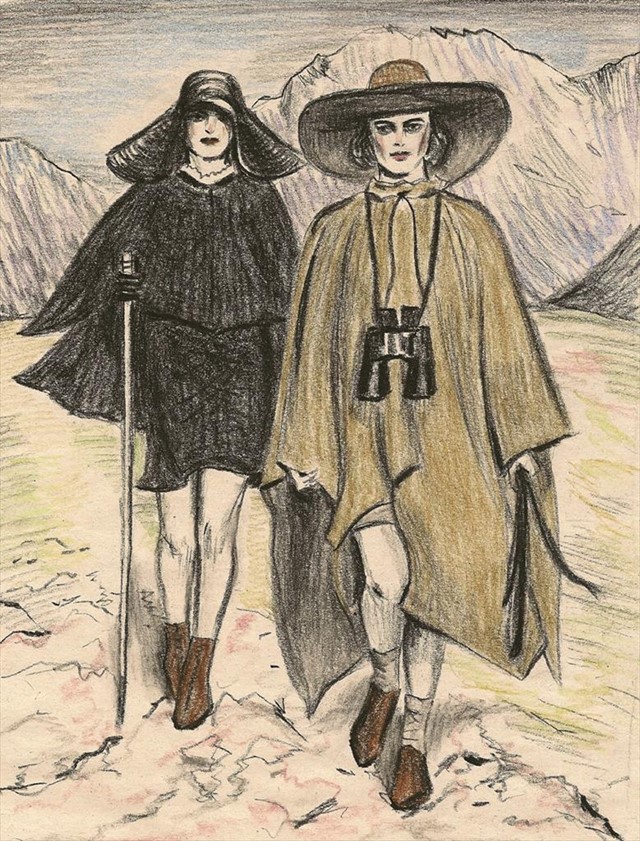

Hussein Chalayan referenced both the historicism and the rugged pragmatism of the garment with a long, khaki cape that fell in asymmetrical peaks to his binocular-toting model's knees. It was in antithesis to the more usual tailoring that comes with safari suiting, giving new fluidity to an otherwise rigid fashion trope.

Such blending of the darted and the draped recalls the work of designers such as Yohji Yamamoto and Martin Margiela, who tend to fuse in one piece the stringent vagaries of structure and tailoring with asymmetrical flapping runnels that spur from sleeves and back seams. Both designers are known for working around the body in three dimensions, rather than viewing it in a flat or linear way from head to toe; and a cape is the ultimate expression of volume and spatial efficiency. This fusion is most familiar in the vented back panels of archetypal trenchcoats peddled by the likes of Burberry and Aquascutum. Caping and draping in small amounts gives breathability to more architectural forms.

Witness Stefano Pilati’s more sober take on the theme at Yves Saint Laurent, with fishtailed black mini-capes that stopped at the empire line and looked like so many chic chasubles. These abbreviated versions are proof that a cape is not incapable of looking business-like. So long as your business takes you to 15th-century Rome, that is.

Hannah MacGibbon's interpretations at Chloé are the type that most fashion followers know, reminiscent of something one might in find in the family wardrobe and which kept our mothers warm during the 70s. Rendered in burnt sienna looped wool, they were open at the front of the body, more cloak-like than cape-like. They bear the distinction of looking thoroughly modern while fitting right in at the Jorvik Viking Centre. This is the beauty of capes: ultimately impractical but oddly timeless.

Zoë Taylor has appeared in Le Gun, Bare Bones, Ambit and Dazed & Confused. She is currently working on her third graphic novella and an exhibition.