As the classic film The Goddess is remastered for the BFI London Film Festival, we revisit our story about its star, Ruan Lingyu, one of China's most extraordinary and beloved film stars

The ghost of Old Shanghai is buried under the concrete and steel of the city’s skyscrapers today, but China’s largest metropolis was once nicknamed the “Paris of the East”. During the 1930s, its tangle of opium dens, brothels and casinos jostled alongside the Shanghai Club (home to the longest bar in the world), the Art Deco Park hotel with its retractable roof, and Astor House, a favourite of Charlie Chaplin and Noel Coward. The city was a hotbed of political intrigue, gold smuggling and protection rackets, while less than a mile from the neon lights, rural Chinese workers lived in crushing poverty.

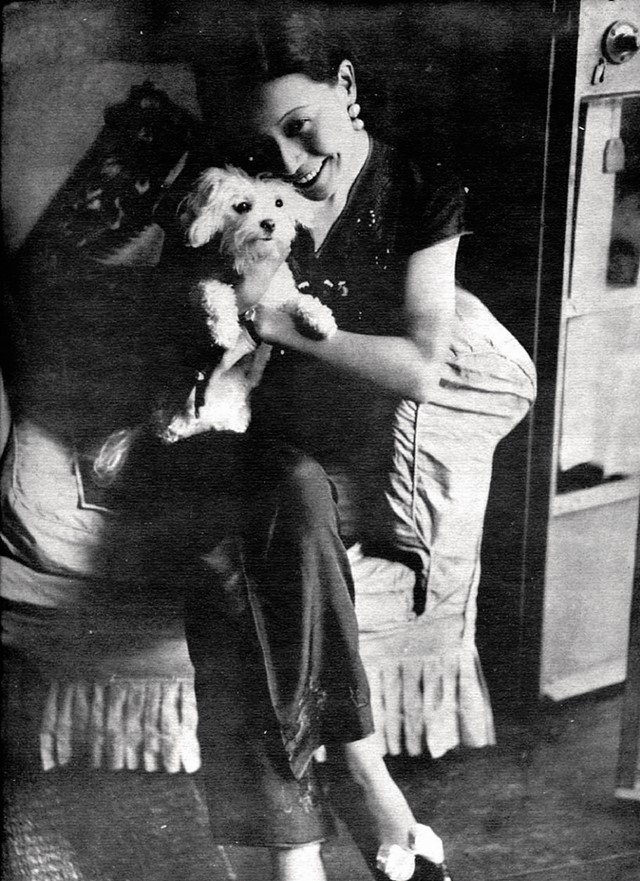

An explosion of creative energy coincided with the real-life drama in the city. Where previously movies had been romantic escapism, a new group of directors dared to make films about real, troubled lives. One of the reigning queens of this golden age of Chinese cinema was the “Greta Garbo of Shanghai”, bewitching young actress Ruan Lingyu. Her chameleon ability to step into myriad roles – prostitutes, workers, teachers and mothers – held a mirror up to the struggles of her country’s people. “She was honest,” says filmmaker Mark Cousins. “Chinese women saw themselves, not some male or western or cinematic hope in her. It was ground breaking, and it changed Asian cinema.” Yet the melancholy Ruan brilliantly translated onto celluloid also pervaded the actress’s life, and a press scandal turned her into an early victim of tabloid culture.

"The melancholy Ruan brilliantly translated onto celluloid also pervaded the actress’s life, and a press scandal turned her into an early victim of tabloid culture"

Born in Guangdong province, Ruan’s father died when she was a girl. To support her family, her mother became a maid for a wealthy Chinese family, and aged 16 Ruan met their son, a playboy and gambler named Damin Zhang. The couple moved in together, and after answering a newspaper ad, Ruan won her first acting role. While Damin gambled away his inheritance, Ruan covered his bounced cheques, supported her mother and transformed her raw talent into a burgeoning film career. By 1930 she had joined the innovative Lianhua studios, and was cast in a series of films tackling social injustice, made by left-wing directors who rejected the old clichés about women, sex and society. The beleaguered streetwalker Ruan plays in 1932’s The Goddess, newly restored by the BFI, highlighted an uncomfortable truth – it’s estimated that one in 13 women in Shanghai were prostitutes at the time. The easy slump of her walk, her nonchalant drag on a cigarette, is still electrifying to watch today – her director Wu Yonggang described the actress as “sensitive photo paper”.

When Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931, the actress fled anti-Japanese riots for the relative calm of Hong Kong. Her relationship with Damin was floundering, and he routinely extorted money from her, threatening to go to the “mosquito press”, or Chinese Tabloids, alleging she was his concubine. Eventually Ruan agreed to pay him a monthly salary for two years to dissolve their affair – a lawyer prepared a secret document, while Ruan returned to Shanghai and took refuge in work. But a second romantic entanglement brought more misery and emphasised the patriarchal society of the time. Tang Jishan was a wealthy (and married) tea tycoon, a patron of cinema with a weakness for leading ladies. He bought the actress a Hollywood-style art deco house in Shanghai and she became his mistress. Damin – spying a lucrative business opportunity – sued both for a share of their assets. The scandal made front-page news, and Tang reacted by beating Ruan, blaming her for his public dishonour – a neighbour remembered him throwing her dog out of a window.

Ruan’s penultimate film, 1935’s New Women, foreshadows the actress’s own fate. She plays Wei Ming, a famous author who commits suicide after being hounded by the press about her private life. In reality the pressures on Ruan were becoming unbearable. The night before she was due in court to defend herself against Damin’s lawsuit, Tang and Ruan attended a wrap party, drank wine and argued violently on the way home. Around midnight, she made a bowl of congee, mixed in three bottles of sleeping pills and wrote two suicide notes. In one, she attacked the press (“gossip is a fearful thing”) and in the second, her former lover Damin (“I’ve been driven to death by you”). Despite everything, her life might have been saved: at 4am Tang found her still alive, but stalled for hours, fearing bad publicity. By the time she was finally sent to hospital at 10am she had lapsed into a coma, and died that evening. When the news broke, a grief-stricken city stood still: a crowd of 300,000 silently lined the roads to watch her funeral procession pass by. Ruan was just 24 years old, but already a screen legend with 29 films to her name.

Conspiracy theories sprang up following her death. False suicide notes appeared, allegedly forged by Damin to deflect Ruan’s last words. He continued to profit by taking an opera on the road based on her life story. The two men in this doomed love triangle met fates described by film scholar Yingjin Zhang as “very Chinese”: after his opera closed, Damin died of an overdose. Tang later went bankrupt, and the former millionaire spent his old age selling tea bags on the streets of Taipei.

Today, the silent centre of this whirlpool of controversy, Ruan Lingyu is virtually forgotten in the west. Many of her films are also tragically lost – critic Jonathan Rosenbaum describes Chinese film history as “written in quicksand”. Her death in 1935 seemed to mark the end of an era. The advent of sound was poised to turn the industry upside down – just months before, Ruan had been smoothing the corners of her Cantonese accent in preparation. Decadent, bohemian Old Shanghai was also on the brink of a turbulent decade; three years later it was invaded by Japan and emerged a shattered city after the second world war, when the People’s Liberation Army took hold. “Older people went misty-eyed when they heard Ruan’s name,” Cousins remembers of a recent visit to China. “She represented a time for them when hopes weren’t jaded, when you didn’t have to talk in double speak, when a revolution promised better lives.” If Ruan is now forgotten, her tradition remains alive in those great actresses – from Julianne Moore to Gong Li – who excel at loneliness, who don’t seek to ingratiate, who vibrate with an inner world.

The Goddess shows on October 14 at the Queen Elizabeth Hall, as part of the BFI London Film Festival.

Text by Hannah Lack