An Intellectual Fashion meets multi-media artist Quentin Jones' to discuss fashion, the language of fashion and idiosyncratic style

Quentin Jones famously graduated in philosophy from the University of Cambridge and in illustration from Central St Martins, bringing together the loneliness of scholarly endeavours and the energy of London creative life. For the last years, she has been bridging the gap between commercial and artistic pursuits, collaborating with numerous brands, from Smythson and Victoria Beckham to Chanel and Louis Vuitton, and making a name as the leading image-maker of her generation. The Fractured and the Feline, her first exhibition presented by the Vinyl Factory at their space in The Brewer Street Car Park, brings together her work in dialogue with Robert Storey’s.

How would you connect fashion to elegance?

I see them as fairly separate ideas: elegance implies a notion of subjectivity, whereas fashion has more objectivity about it, even if it is not a necessity. The evolution from the noun to the adjective is also quite a shift: it is quite different to talk about “fashion” or about something being “fashionable”. If there was a Venn diagram of their meaning, you would have fashion as a big circle, and elegance as a very badly defined small one: sometimes they cross-over, and their intersection is often quite blurry depending on who is drawing it in their mind.

"Elegance implies a notion of subjectivity, whereas fashion has more objectivity about it, even if it is not a necessity"

What is the role of history and art history in your conception of fashion?

To start with I think that in most instances fashion is a form of design, rather than art. A designer always has to be outward-looking, whereas an artist can always take a more insular approach: a designer responds to a brief, and part of the brief is to engage with the history that precedes his work. It is part of an ongoing stream of ideas – following a thread.

Would you describe fashion as a language and a discourse, as Barthes did?

In that instance, fashion design and fashion theory are quite similar: fashion design is embedded within the society that it is in, and fashion theory likewise. This position implies that they are somehow the discourse of that society.

The word "intellectual" was coined in a time of great political distress. Does fashion have a political role? And in what way?

Fashion can contain political expression, and politics can have a great influence on fashion. However, fashion cannot have a great impact on politics: you can point examples when fashion has had an impact on politics, whereas it would be very difficult to do it the other way round.

How would you relate the concept of "fashion" to the one of "style"?

“Stylish” and being “fashionable” are two descriptive terms, with a subjective base – which, again, needs to be differentiated from the substantive: style means taste, whereas stylish is an often complimentary description. Fashion is something quantifiable: if more people wear it, then it is fashionable, whereas you cannot quantify style.

What does fashion have to do with intellectuality?

It has to do with an approach: you can approach fashion in intellectual ways, and even in the thorough ways of academia.

"Fashion is something quantifiable: if more people wear it, then it is fashionable, whereas you cannot quantify style"

You work with imagery and setting image in motion. This experience of imagery exists very much in the present. How do you keep together the present and the historicity?

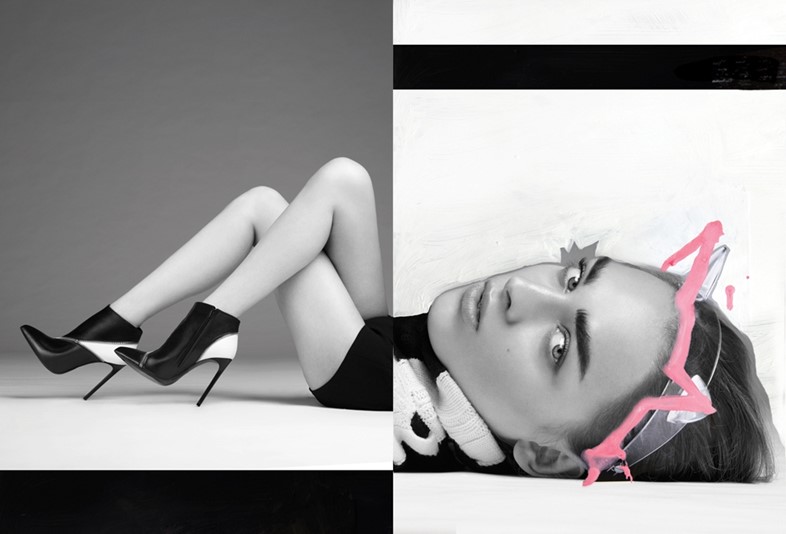

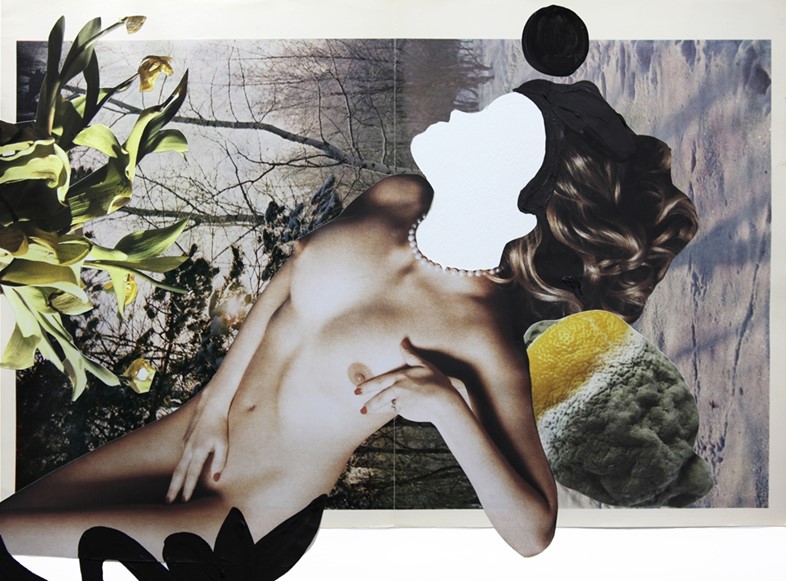

Collage has existed for a hundred years; so when you do it, there is a sense that you become part of a conversation with the Dadaists, and all those who practiced it before you do. It has references that feel historical, timeless, and disconnected it from this moment. My personal approach and my instinct maybe are to take this legacy and make it rougher and more contemporary – more violent than what existed in history, and bring an irreverence into it that maybe was part of it in the past, but is mine, and comes from the present. There is another element to it, which is the fact that I am a commercial artist: it’s always a new season, always a new issue. There is a need to always keep up with the trend, whereas if I were only dealing with fine arts, that would become less important, and I could get lost in myself or in history.

Your work is very idiosyncratic, and yet you engage with fashion. What is the tension between your individuality and the fact that you do commercial work?

I’ve been quite lucky: when a brand or a company approaches me, they want what I do rather than wanting me to become part of what they do. There are so many photographers and filmmakers around, so if you want someone to give a more polished version of your brand, you don’t come to me and ask me. People usually come to me because they want to have that multi-media, art perspective on a fashion situation. That’s how I have been able to keep my identity through all these different projects. Putting together The Fractured and the Feline with the Vinyl Factory has actually been a very nice opportunity to see that there is identity in what I do and to feel good about the fact that there is something recognisable about it. As an image-maker, you sometimes worry that there is no thread in your work, that you get lost in the emptiness of commercial pursuit, going from one TV commercial to another, doing this for this brand, that for another brand. Maybe there is a risk, which is to be unable to keep a personal narrative ongoing. Doing this has enabled me to feel that there are things within me: I love an element of accident, planning a thing, and then doing ten different versions, and choosing one. I have been to reflect on my work, and it’s sometimes important in order to keep your individuality.

The Fractured and the Feline runs until December 13 at The Vinyl Factory. In two weeks Donatien will interview the philosopher Emanuele Coccia.