Producers Sam Gainsbury and Anna Whiting talk their myriad collaborations with Alexander McQueen

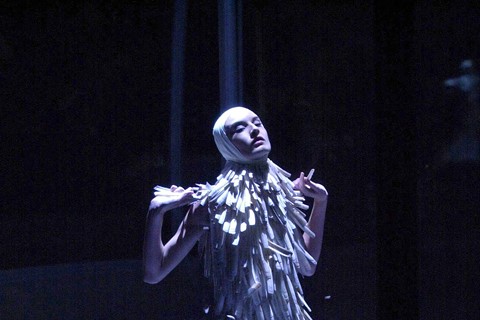

Few designers have sought to redefine and challenge the expectations of what a fashion show could be quite like Alexander McQueen. “The shows are the culmination of everything that goes around in my mind,” he once said. “I need inspiration. I need something to fuel my imagination and the shows are what spur me on, make me excited about what I’m doing.” Together with his longtime collaborators and producers, Sam Gainsbury and Anna Whiting, the shows he staged became the purest expression of his wild, dark and unfettered imagination. Nothing was impossible for him – it was the place where he could bring a nightmarish Joel Peter Witkin tableaux to life, commission Michael Clark to choreograph a performance based on the Sydney Pollack movie, They Shoot Horses Don’t They? or encircle a model in a ring of fire. It was through the experience of these spectacular, breathtaking and at times visceral presentations that one could gain the greatest insight into his mind and his obsessions – as he used the shows to explore themes both grand (Plato’s Atlantis referencing ‘Darwin’s theory of evolution in reverse’) and intimate (La Dame Bleue where he paid homage to his late friend and muse, Isabella Blow.)

Now five years after his suicide, McQueen is to be honoured with the Savage Beauty, a major retrospective at the Victoria & Albert Museum opening this month. Originally staged at the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art in 2011 (where it attracted over 660,000 visitors, making it the eighth-most visited exhibit in its 142-year history), not only does Savage Beauty represent a homecoming for the iconic British designer but will serve a poignant tribute to his artistry and vision. Insiders spoke to Gainsbury & Whiting ahead of the exhibition.

Sam, you first worked with McQueen on the S/S96 presentation, The Hunger. How did you first meet and what was your first impression of him?

Sam Gainsbury: I met Lee through my friends Janet Fischgrund and Katy England in 1994. My first impression was that he just said what he thought. There was no filter and I immediately wanted to help him. He had that effect on everyone. He was just very honest and had such clear ideas that you just wanted to make them happen for him.

Sam and Anna, you met working on a music video for Tricky. How did your experiences working in that field prepare you for what you would go on to do in fashion?

SG: When I first started working with Lee, fashion shows were primarily held in the official tents. Even the more experimental designers like Vivienne Westwood showed on a raised white catwalk with simple lighting in the official BFC venue. Lee came to me with the clear intention of not doing this because he had heard that I worked in music videos and he wanted to do something different. The first show we did together, The Hunger was actually held in the tent as he had absolutely no money to finance anything else. We added a red light to the back wall and that was about it. I think we all felt at the time that Lee’s clothes deserved more. After The Hunger, he was eager to show in a venue he could own visually. For Dante at Spitalfields, Christchurch, my first real show production, I introduced him to people that I worked with in music videos, and this started a new language for his shows, more cinematic basically.

Anna Whiting: I joined the production team in 1997 for Untitled. I think coming from a film background, specifically music videos and live filming helped. I was accustomed to being laterally minded in the approach to finding ways to achieve our goals with limited resources.

Prior to McQueen, fashion shows were far less spectacle and had less of a storytelling element to them. Was part of the excitement of working with McQueen the opportunity to push the boundaries of what could constitute a fashion show, almost into the realms of performance art?

AW: I don't think anybody working with Lee at the start felt that they were pushing boundaries or creating art. It all felt very natural and instinctive. I think we probably all became a bit addicted particularly with the early London shows when we were experimenting with ideas. I always looked forward to meeting up each season and Lee telling us what he wanted to do… and then figuring out how to do it.

Sam, you were once quoted saying, “He could never design a collection without knowing what the show was.” What was the working process with him at the start of every season?

SG: We would speak very quickly after a show sometimes as soon as the following day to discuss the next one, as Lee became bored with a show as soon as it was over and would just move on, always wanting to make the next one better. Sometimes the process was very easy, as simple as him having an idea and telling us exactly how he wanted to do it, other times it took longer to get there and several ideas would be discussed and developed before we arrived at the one he wanted to go with. He couldn’t really relax until the show concept was finalised and he always wanted to do this early into the season as the show often inspired ideas for the collection.

McQueen shows over the years have featured everything from a lava runway exploding into flames (Joan A/W98), Voss – which was staged inside a two-way mirrored box – to a real‐life hologram of Kate Moss. What was, technically, the hardest show to realise?

SG: Technically, Plato’s Atlantis was the most demanding as It involved so many different departments with the added pressure of the live broadcast. It was such a singular vision and had to be delivered as such with no compromises

AW: Technically, I’d agree it was Plato’s Atlantis. The number of departments all needing synchronicity for the live show was a challenge.

McQueen has said in the past the only show that made him cry was No 13. Which McQueen shows have been particular highlights for you over the years and why?

SG: No. 13, obviously because it was Lee’s favourite show and it made him cry. It was also a turning point for all of us. We got such a high from pulling off a show that could be that emotional. Afterwards we were always trying to beat it.

Plato’s Atlantis was livestreamed on SHOWstudio and was so popular it crashed the website. How has the internet and livestreaming where the viewer gets a front row seat and can zoom in on the smallest micro detail changed what you do at Gainsbury & Whiting?

SG: It hasn’t really changed what we do at all. A live feed of a show now is as obligatory as a lighting rig or sound design. It’s just another element to facilitate in a production.

Even for a McQueen novice like me, experiencing Savage Beauty at the Met was such an emotional experience. Was working on it a bittersweet time? Did it bring any surprising insights into the way he worked?

SG: We were all still mourning Lee’s death when we were working on the original Met exhibition and perhaps the visitors sensed that. It was always important to Lee that you felt something when you went to one of his shows and that the audience connected emotionally in some way to his work. The fact that both exhibitions at the Met and the V&A have been delivered by Lee’s friends and colleagues has meant that we’ve been able translate the visual language of his shows authentically. Ultimately, Lee was a storyteller, so we’ve tried to translate his stories into the exhibition.

The show at the V&A is a homecoming for McQueen who has always been influenced by his London roots and frequently used English references in his work. What can we expect to be different from the Savage Beauty exhibition at the Met?

SG: It is fundamentally the same exhibition as we felt it was important to bring Savage Beauty to London. There were so many people who didn’t get to see it first time around and it's great to bring it to the city where Lee came from and where he took so much inspiration. The exhibition space is bigger than before which has given us the opportunity to make some of the galleries much larger with more content. Lee’s earlier work is represented more in a new London gallery. There is also a gallery just for the Kate Moss hologram. Lee always wanted to show this independently as a work of art, and so we felt it was important to do so in the V&A exhibition.

You formed your production company in 2000 and are about to celebrate 15 years in the business. How has the working collaboration between the two of you grown in that time and how do you see the company evolving for the future?

SG: We will continue to collaborate and look outside of the fashion industry for creative people to work with. When we first started the company we introduced talent from film, theatre and art to the fashion industry. We are now using the same philosophy by introducing creatives from fashion into the exhibition and technology worlds. Which is exciting. Lee McQueen taught us both to be brave and that everything is possible. Because of him, Gainsbury & Whiting will always be a company that encourages its clients to be original, take risks and create memorable fashion moments.

Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty, in partnership with Swarovski, supported by American Express, with thanks to M∙A∙C Cosmetics, technology partner Samsung and made possible with the co-operation of Alexander McQueen, runs from March 14 – August 2.