After her Fashion In Motion show at the V&A, we spoke to Grace Wales Bonner about her inspirations

When Grace Wales Bonner presented her Central Saint Martin's graduate collection, it blew the industry away. Combining Fela Kuti with Coco Chanel, Carl Van Vechten with blaxploitation, it was like diving headfirst into a celebration of (often-ignored) black culture. By both challenging and embracing stereotype, Bonner's work is simultaneously beautiful and provocative. After her equally brilliant second collection was exhibited at the Victoria and Albert Museum's Fashion In Motion event, we spoke to her about what inspires her both theoretically and visually.

How has your own identity played into your collections so far?

So far the collections have been a personal exploration of my own identity. Black culture as a reference point has been a really big fascination for me, both academically and visually, and I guess that it’s been a way of me understanding a side of myself. Fashion has become a way for me to talk through and discuss those topics, trying to visualise and work through the ideas that I’ve been reading about.

During a time where exploring black identity is often restricted to looking at ‘urban’ or ‘street’, your references seem really different…

Well, the new collection was an extension of my graduate collection, where I looked quite specifically at 70s representations of blackness. The work of people like Malick Sidibé, Samuel Fosso and Seydou Keïta was really important because it was black people taking the camera and turning it on themselves. They weren’t being documented or having an idea of who they are and what they represent imposed by a western lens or someone else’s idea of things – it was a complete ownership of their own representation. Those references led onto the next collection, which was about a spectrum of blackness being created both through a western lens and also through black culture and its aberrations. A real pan of different permeations of blackness that have been represented through time.

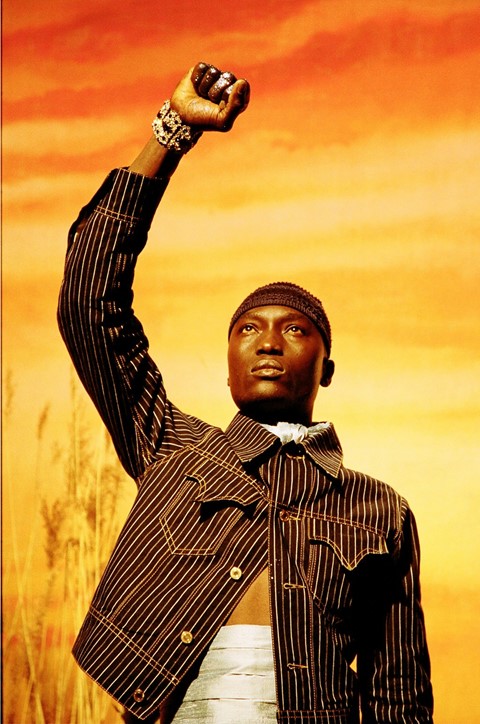

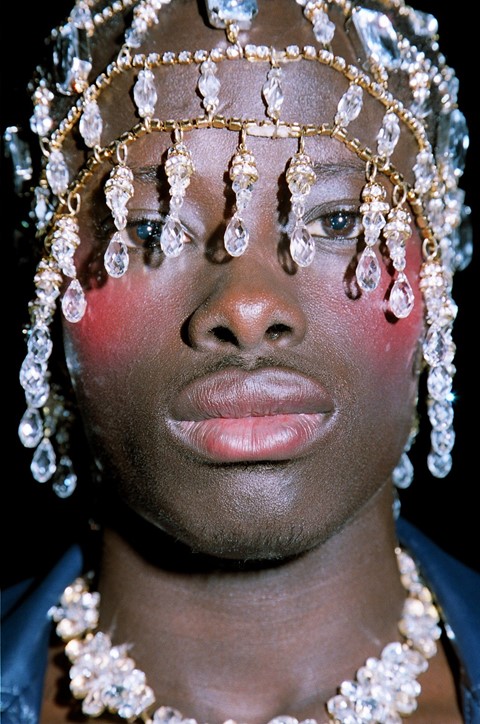

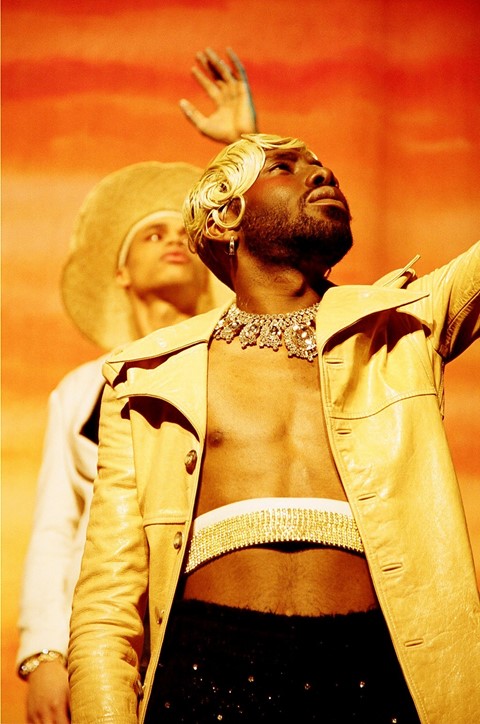

I was particularly interested in 19th century orientalist paintings and depictions of North East Africa. There was a real softness and regalness about the way that black men were represented, but also something quite exotic and mystic. It was still an exaggerated, western interpretation of blackness but, even in that, there was something really beautiful. So, the last collection was about exploring the miscommunication that can come from trying to represent a different culture, but also the beauty that can come out of that. Really, it’s just about exploring how people interpret things and seeing the beauty in those different representations. We often don’t think about men being beautiful. The way I was trying to approach it, and those paintings, was through a softness and that really came through in the clothing and casting and everything.

Yes, the boys in the show were so beautiful. It looked like Paris Is Burning meets Malick Sidibé. How do you work on casting?

A lot of the boys have become friends of mine now and it’s great because we have a good relationship so the collection evolved organically as I got feedback from them. It was about trying to show a spectrum of blackness: we had mixed race guys, we had guys from Uganda, someone from Sierra Leone. We wanted to celebrate different tones rather than just one kind of blackness, which is often either hyper black or urban. It was about showing a broad, introductory range of different things.

Why did you call the collection Ebonics?

In terms of research for the collection, I was looking a lot at the Harlem Renaissance poets from the 30s like Langston Hughes and Claude McKay. Then, I was also really interested in the work of people like Marlon Riggs and Isaac Julien, looking at black homosexuality and its representation. Anyway, I was listening to all of this poetry and thinking that, even just listening to the recordings, you can tell that the person is black just by how they are speaking. So, Ebonics is basically just the dictionary of blackness, of how you know that something is black – thinking about ideas of sound, rhythm, intonation and authenticity. About how you can define or recognise something that’s black. It’s basically a celebration of all of the different sounds of blackness.

How do the techniques of fabrication and the technical elements of construction you incorporate engage with a history of blackness?

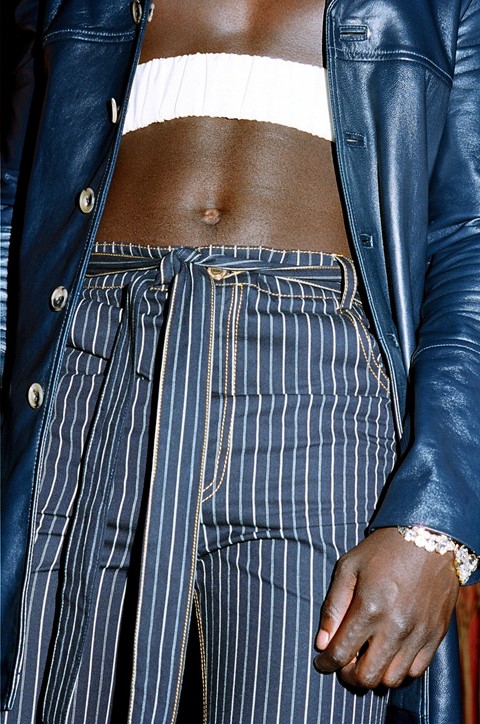

I was trying to merge different crafts and traditions together. I was thinking about elements like the cowry shells, which were once used for currency, and European ideas of wealth, which would probably be represented by diamonds and Swarovski crystals. So, I tried to make a collision between these two notions. And with the raw Indian silks and couture techniques, I was trying to create a sense of opulence. It’s still something I’m developing, it’s not a resolution, it’s just an early exploration of that.

Are there any other people who you think are challenging representations of black identity at the moment in an interesting way?

I’ve spoken about Kerry James Marshall a lot; I think that he is doing something pretty radical in the art world. He has his own agenda of representing blackness, and he’s introducing it to the art community in a very unapologetic way. He makes the most beautiful, captivating paintings that also spread a really important message to black artists and black people about having presence in the art world, and the world generally. And Frank Ocean is pretty amazing, I’m really excited about what he’s doing at the moment. He’s breaking all of the rules of what you expect from an RnB singer: he’s really making something beautiful and timeless.