We examine the collection that Kurt Cobain set on fire and the fashion industry condemned

“Grunge is anathema to fashion,” wrote Cathy Horyn in her 1992 show report of Marc Jacobs' Perry Ellis collection. "Rarely has slovenliness looked so self-conscious, or commanded so high a price.” Hers was one amidst many condemnations that rained down from journalists, editors and buyers alike. Just weeks after the models left the runway in their cashmere plaids and undone nightdresses, Jacobs was summarily fired from the brand and the line itself was shut down. The pieces never went into production – on paper, it should have signaled the end of his career.

Instead, S/S93 at Perry Ellis was the start of something, marking Jacobs as a pioneer of youth culture and a renegade when it came to inspirations. This fact was cemented earlier this year when, after twenty years of reflection, Horyn officially retracted her statement in a piece for New York Magazine. In it she revoked her "violet-scented peevishness" and interviewed Jacobs on the collection he claims is his favourite work. Today we examine what it was that inspired such a vehment response, from critics and grunge musicians alike.

The Show

Models wore floating chiffons teamed with Doc Martens, cashmere thermals with oversized plaid shirts tied around their waists and baggy nightdresses. Hair was stringy and matted, cheeks were flushed as they marched down the runway to the sounds of Sonic Youth, Nirvana and L-7. It was an explicit homage to the trends that had emerged in Seattle from working class practicality, been propelled into general consciousness by the success of bands like Nirvana and ended up in Hollywood through Cameron Crowe's 1992 film Singles. "I wanted them to look the way they do when they walk down the street, which is not dolled up," Jacobs explained in a 1993 New York Times interview. "I didn't want them to look like drag queens, and I didn't want them to look like creatures... That's the way beautiful girls look today: they look a little bit unconcerned about fashion."

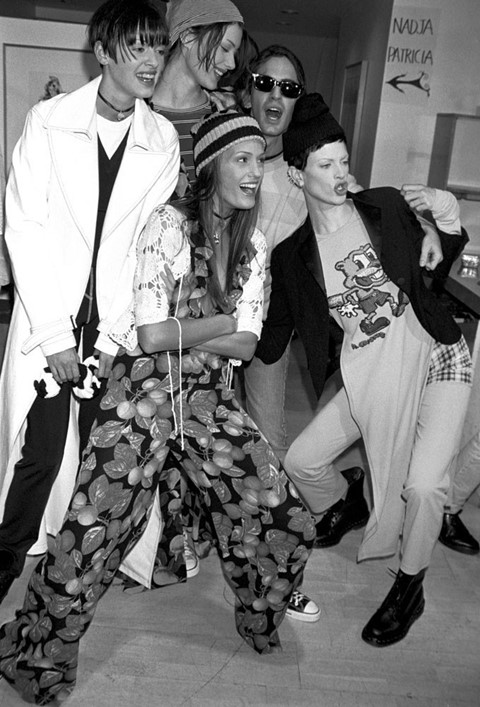

The People

Christy Turlington opened the show; Kate Moss and Kristen McMenamy closed it. In between appeared Tyra Banks, Naomi Campbell, Yasmin Le Bon and Carla Bruni. There couldn't have been more icons of the nineties crammed onto the catwalk and, two months later, Grace Coddington dressed some more in the pieces for an iconic Stephen Meisel shoot for US Vogue titled Grunge and Glory. When production was ceased on the collection, Jacobs sent samples to Courtney Love and Kurt Cobain but, as Love later told WWD, "We burned it. We were punkers – we didn’t like that kind of thing" (a lone bonnet and pair of electric blue shoes survived). From the musicians to the models, everyone involved was an iconic part of early 90s counter-culture – and Marc Jacobs was enthusiastically channeling (or appropriating, depending on your perspective) it all to subvert the high-octane glamour that surrounded so many other fashion houses at the time.

The Impact

At Milan Fashion Week the following season, Suzy Menkes handed out hand-made badges printed with the words "Grunge is Ghastly". Trish Donnelly condemned the collection as "grunge garbage" and a New York magazine headline read “Grunge: 1992–1993, R.I.P” (perhaps accurately – later that year, Kurt Cobain was photographed wearing a t-shirt that read "Grunge is dead"). On top of it all, Jacobs was fired from the house he'd been hired to invigorate.

But, from the ashes of his (literally) burned and reviled collection, he emerged phoenix-like in 1997, when Bernard Arnault hired him for Louis Vuitton and his career once again skyrocketed. And, while Jacobs might have divided his contemporaries – half of whom hated that he was ripping off their style, half of whom just plain hated it – the collection's self-declared "anti-chic anti-glamour" has proven to be one of fashion's pivotal moments; one that, decades on, is still garnering (now positive) column inches from some of its greatest names.