We examine our favourite of the RCA's MA offerings under the tutelage of new Head of Fashion, Zowie Broach

When, last year, the legendary Wendy Dagworthy left her role as head of fashion at the Royal College of Art, the task of replacing the “high priestess of British fashion” was a daunting one. When, last week, the first collection was shown under her successor, Zowie Broach, it was clear that the new appointment was brilliantly considered – and offered a subtle, yet distinct revolution in the way that one of the world’s most revered fashion schools exhibits its graduates.

“I looked at Dada because it was childlike and pure, Bauhaus because it was functional and truthful, and then punk because it was for everybody” explained Broach on her approach to the role; and nothing manifested the three as succinctly as the food that was served during the presentation. Midway through the (36-student strong) catwalk, the procession stopped – interrupted by what, at first glimpse, appeared to be a performance piece. Tens of people, each dressed in a lab coat, swarmed into a space that moments before had contained models. When they disappeared, what was left behind were giant tables piled high with food: one with asparagus, one with cherries, ordered in precise rows, jewel coloured and inviting.

“Food is about people,” Broach explained, “and we wanted it all to be an experience, a performance. I wanted people to have to get up from their seats, walk over to the tables, bump into someone, have a chat about the collections they’d seen so far.” And they did; once everyone broke through the awkward moment of thoroughly British hesitation and started grabbing at brownies, groups formed around the tables, discussing the choreography of the show (orchestrated by Joe Moran), people went for a cigarette with their friends or grabbed a drink. When everybody sat down, they were ready to watch another set of collections, rather than fashion-fatigued and a little restless.

“We just discussed what’s not working,” she explained. “We considered every aspect and it needed it to be elegant and sharp; plus, I wanted people to have conversations and meet new people. That’s the world I grew up in; back in the mid-90s, London was much smaller, there was a multi-tribe of different disciplines, different visuals. As it’s got bigger, it’s become more pocketed.” And Broach’s focus on bringing people together, on engaging with what the students themselves want from their presentation and who they want invited to the show (apparently Gary Card and Edward Meadham, who were both in attendance) was made clear through not only the canapés and guestlist, but through the designs themselves. We spoke to some of the standout exhibitors to find out a little more about their work.

Melanie Lewiston

"It was a performance piece," said milliner Melanie Lewiston, whose collection was slowly sent out on a melancholic procession of young boys, "and it was Zowie who allowed that to happen. I wanted to take it back to the origins of theatrical performance, where all the actors would have been young men. I saw a production of The Duchess of Malfi, and found out that the original costumes would have been embroidered with real silver thread and the boys' faces decorated with pearl dust, so that they would shimmer. It was a magical moment: this smell, this darkness. So that’s how I envisaged it."

Rooted in the loss of her mother, Lewiston's immaculately-created pieces were somehow almost painfully emotive – as she explained, "Zowie was really keen to see the heart of people's work, and that was the heart of the show. In any catwalk show, it should be the person's whole being that you see." And this intimacy came through not only the performance, but the pieces themselves; with a perfect hand-made finish to the leathers, intricate traditional techniques and ceramics mask lined with Lewiston's own deconstructed opera gloves ("I just couldn't find the right fabric for it") they each made for a collection that was as precisely considered as it was impactful.

Vivi Raila

"I started out looking looking at Ikebana, the Japanese flower arrangements, because they aim to create a perfect harmony between different elements and I was really interested in the idea of perfect composition. I was also looking at 17th century Dutch still lifes; the darkness, tragedy and opulence of the cut flower – and then looking at how I could do that, and the Ikebana, with clothing. Then, I saw this 60s Czechoslovakian film called Daisies, which is amazing; it's about these girls who think the world is spoilt and so they should be spoiled too and they go around dressing themseves up and doing pranks."

Vivi Raila's collection, worn by models who quietly and casually strolled through the auditorium ("I didn’t want it to be like ballet, because this is not about ballet, it’s about life"), was an exploration of femininity – but free from the whimsy or explicit sexuality that could accompany floral lingerie. "Even though it’s a lot of skin, I still wanted boots on the girls; high-heels would look a bit too careless," she explained "and I wanted to look like a girl who dressed herself and knew what she wanted." Exquisite lace, sheer chiffons embroidered by Alice Timmins or painted on with acrylics by Raila, precisely yet relaxed undone styling that optimised the modular pieces' flexibility: all united for a collection that turned what could have been Courtney Love babydoll insouciance into a beautifully elegant exploration of fragility.

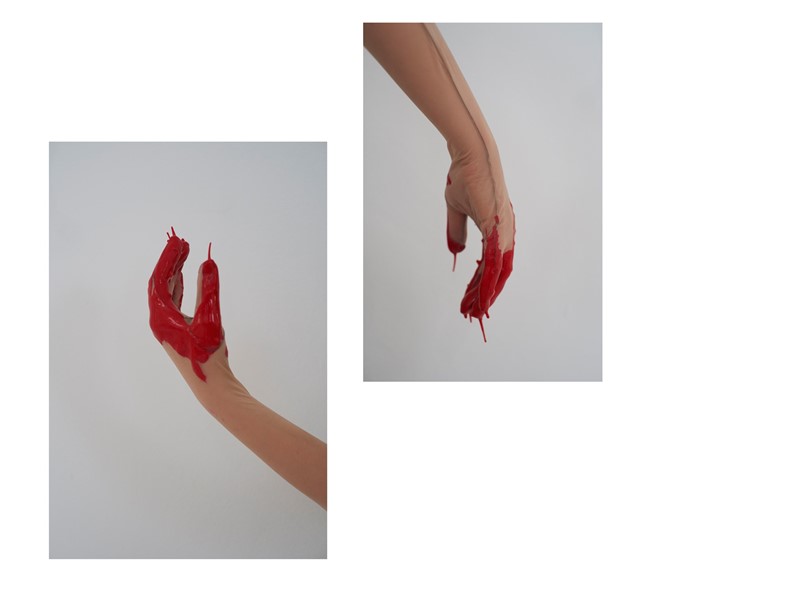

Hannah Williams

Inspired by the work of sculptor David Altmejd – whose work is preoccupied with the creation and evolution of the pieces themselves – Hannah Williams' gruesomely mesmerising creations were a particularly captivating moment. Models looked as though they had been dipped in layer upon layer of latex which puddled around their perspex platforms and dripped from fingertips, each piece sculpted to an individual. "I literally moulded the garments onto live models... originally, I wanted to create a performance and do the show that way," explained Williams. With shoes tied on with bits of rope and a considered element of sloppiness, the impact was Carrie-esque and organic: "I don’t want it to be about these pretty little delicate garments. It should be about this ready-to-wear, rip-and-go, just rip it off and just tie it on."

Mark Glasgow

Menswear designer Mark Glasgow explained that his wonderfully-hued intepretation of the seventies was his own version of "a gay utopia. I'm from quite a conservative family in Northern Ireland and so I wanted to recreate an idyllic San Francisco." Set to a distorted revisioning of The Beach Boys Good Vibrations (performed by The Langley Schools Music Project), his candy-coloured palette – inspired by a 70s photo album – somehow communicated something beyond the Arcadian, an underlying sadness that Glasgow described as "a tongue-in-cheek bleakness." With jackets carefully and subtly embroidered with David Hockney figures and Harvey Milk sitting in neo-Impressionist paradise alongside Glasgow's family, even the most miniscule details of the collection had a bittersweet beauty to them. "It's protest, in a more beautiful way," Glasgow summated, "it's an idea of where we're headed."