Deep in the Louis Vuitton headquarters in Paris, amongst all those perfect new leather goods, is a rack of clothes like no other. They are the fruits of legendary London club kids like Leigh Bowery (1) and Melissa Caplan and forgotten London design heroes like Christopher Nemeth, Stephen Linard, Modern Classics and Rachel Auburn. These pieces aren’t made from flawless cashmere or vicuña, they’re fashioned from cheap fabric sourced from the East End of London in the 1980s, glitter and dreams. They are the ghosts of a bygone time, the results of boundary-less creativity and hedonistic pleasure-seeking, a world away from the precision of today’s high fashion industry. But that’s why their owner Kim Jones, the man behind Vuitton’s menswear, loves them.

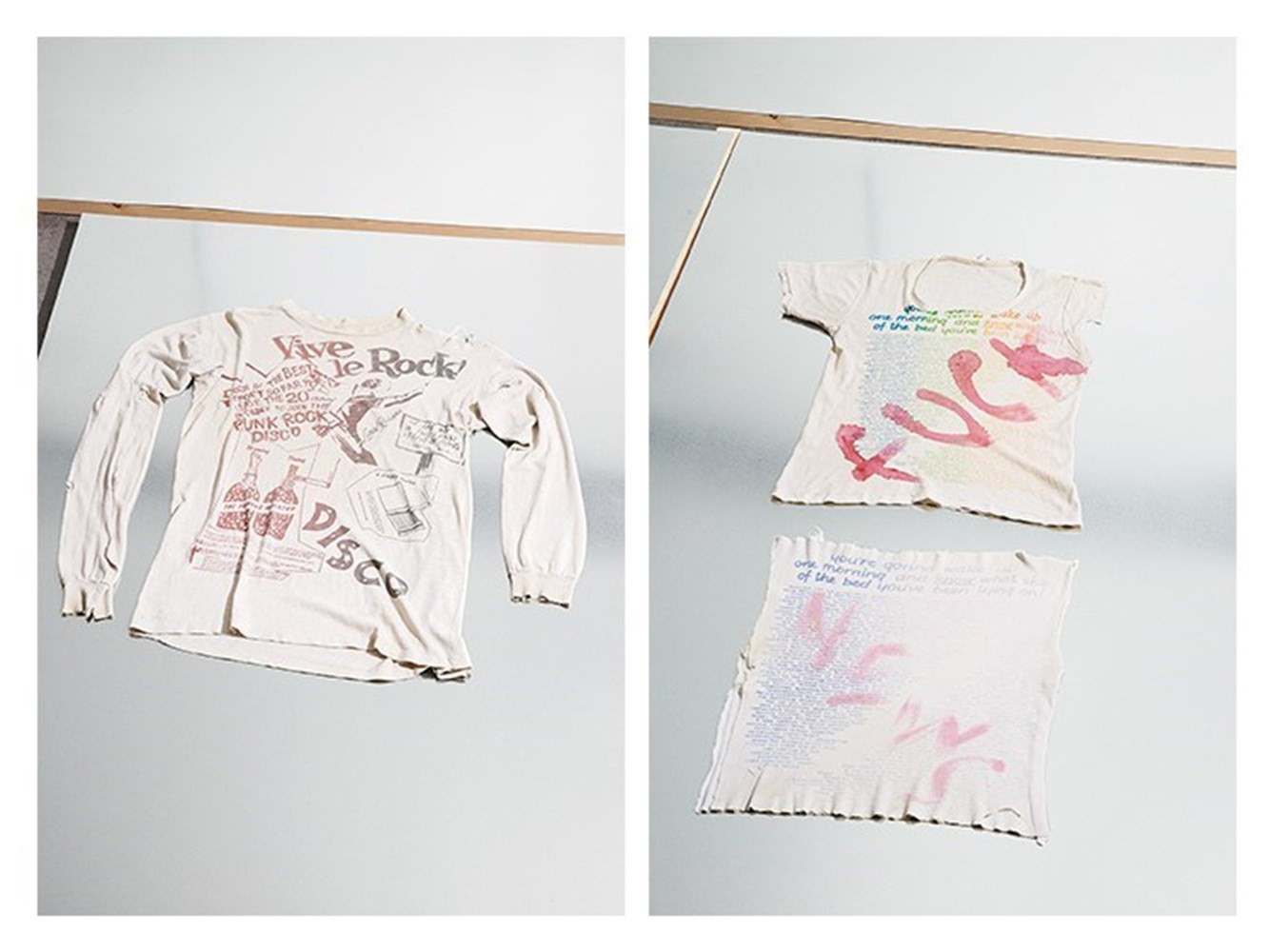

Jones has been collecting for over a decade and has amassed well over 100 pieces, one of the greatest fashion archives around. Aside from Nicola Bateman, Bowery’s widow – the performance artist was openly gay, but the two had a close companionship – Jones has the biggest Bowery collection, over 30 pieces dating as far back as his Pakis From Outer Space period in the early 80s. Mixed in amongst them are precious early punk pieces from Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren’s iconic shops, Let it Rock, Sex and Seditionaries, plus the odd bit of 70s Issey Miyake and early Jean Paul Gaultier. Over the course of our conversations, which take place around the SS15 Vuitton menswear show, he acquires six more Bowery pieces, created in collaboration with corset maker Mr Pearl in 1987 as costumes for pioneering choreographer Michael Clark. For Jones, the search never stops.

Jones and I first meet in London, where the majority of the archive lives, fumigated and wrapped in plastic in his home (only recent purchases remain in Paris). He’s just given a talk to MA Fashion students at Central Saint Martins, a few weeks after the esteemed course director Louise Wilson – a dear friend and mentor to Jones – passed away, and it’s got him musing on the way fashion has changed since the heady days of Bowery and co., who’d spend their time fashioning crazy looks just for their own pleasure and the amusement of the friends they saw at iconic clubs like Taboo. Nothing was about commerciality – Bowery only ever did one show, London Goes to Toyko, a group showcase for British designers in 1984. He didn’t care about selling stuff, Jones is keen to assert. “I think it’s just the freedom of it all that’s amazing,” explains Jones. “Especially now because you’re in an age where you have to be commercial. When I was at Saint Martins the one thing that you had to be was yourself. But everything is blurred lines these days. What was nice back then was the different tribes – the House of Beauty and Culture with Nemeth, Richard Torry and John Moore, then you have Leigh and Rachel Auburn and Trojan, then Westwood and McLaren and then BodyMap – there are crossovers but they all had such strong identities. That I find refreshing.”

It was actually while a student on that same MA course that Jones began his collection, though then it was more about finding something to hang on the wall of his student flat than commemorating London’s bravest and boldest dressers. He bought a Seditionaries top from Steven Philip at acclaimed vintage haunt Rellik, who is now Jones’s closest collecting confidant. Philip recalls them first meeting back when Jones was a teenager. “I’ll always remember I met him in Soho Square. He was young, 19 or something. And we clicked straight away because even then as a young boy he had a passion for London 80s clubland. And I was kind of part of that at that time. We started off seeing each other like two times a year. But over the past 12 years or so we’ve become really close friends and we speak every week now,” he explains. “He knew I collected stuff like Westwood, and Kim’s always had his eye on things that he likes.”

Indeed, Jones is something of a magpie. The more we talk the more I realise he’s actually obsessed with lots of stuff. He’s always got his eyes open, a trait he perhaps inherited from his father who, along with Jones’s uncle, was an avid art collector. As he puts it, “I’ve never been a dresser upper, I’m more of a voyeur.” So, when I visit his Louis Vuitton office in Paris I find it’s filled with letters written by Diana Vreeland, a collection he’d neglected to mention at all – “Oh, I just found them on eBay and around and about,” he shrugs. Above the bed in his home is the painting that hung in Vreeland’s apartment, while the rest of the walls are adorned with a huge collection of artworks by the Bloomsbury set including pieces by Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell. Talk to Jones about anything – art, literature, music – and at random points during the discussion he’ll exclaim, “I’ve got this!” or “I’ve got that!”, whether it’s a dresser owned by Virginia Woolf, or Edith Sitwell’s chair, or paintings by Trojan (Bowery’s partner-in-crime), or, in keeping with the Westwood theme, Johnny Rotten’s iconic mohair jumper, which Jones keeps in his fridge so it doesn’t rot. “I’m The Organised Hoarder Next Door,” he quips.

While he won’t go to anyone else but Philip for his Seditionaries stuff – there are just too many fakes out there – Jones’s sources are also diverse. He’s found pieces by Westwood in charity shops, Japanese thrift stores and on Etsy, and on one particularly good day, a jacket from her Witches (2) collection on eBay for £400 (a similar piece sold at auction just a few months later for ten times that amount). What’s not haphazard is his focus. He may dabble in furniture and ephemera, but when it comes to fashion he knows exactly what he’s after. He only collects a few Westwood collections. Witches from 1983 is his greatest obsession because of those great Keith Haring prints, but he’s recently started getting into Buffalo (also known as Nostalgia of Mud) and Savage. He doesn’t want the stuff everyone knows, so Galliano’s out. Similarly collecting BodyMap has never been a major focus – there’s just too much of it out there – as he’s interested in the underappreciated names and the earlier work that’s hard to find. Nemeth – a former artist whose signature was clothes constructed from various patches of salvaged material – is his favourite when it comes to menswear. Similarly, he loves Modern Classics, an 80s label so forgotten that even several established fashion critics I speak to can’t place it. Jones has a fabulous jumpsuit by them – “No one else has got it apart from David Bowie,” he notes.

Jones’s current obsession is completing full looks, rather than just collecting individual pieces. This is the ultimate challenge when buying vintage. Philip explains, “Recently I sold Kim a Buffalo outfit, and the Buffalo outfit consisted of the Buffalo hoodie, the Buffalo leggings, the Buffalo underskirt, the Buffalo printed overskirt, the Buffalo hood top, the Buffalo bra, the Buffalo hat – it just goes on – the Buffalo socks!” Philip can relate in his own collecting impulse. “When you’re missing a part of that jigsaw, you have sleepless nights. Especially if you just need one piece. Even today I’m still looking for one piece of a whole Pirate outfit. I’m short one sash and it’s driving me mad.” Jones is as obsessive about Witches. He tells me with pride to look up Steven Meisel’s 1983 Vogue shot of Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren with a model clad in Haringcalligraphied separates – “I’ve got all the clothes in that picture,” he smiles.

Today, Jones is tirelessly on the hunt for photographs of people in the collections, whether it’s Scarlett Cannon manning a club guest list in bespoke Bowery or Mark Vaultier on the door of Taboo. Those snapshots are what show the homes and contexts of the clothing. Aptly, it’s these kinds of images that first got Jones into fashion and clubland as a whole: “'When I was 14 I got all these copies of i-D and The Face from my sister and I just thought, wow, people live like that. I’d grown up in West Africa as a kid and to see that was amazing.” While Jones is excited by Westwood – amazed by the innovation, fabric techniques and patterns – he’s moved by Bowery. These are clothes with secrets and stories. He loves the idea of the door whore, or the man in the street in broad daylight in full sequins. Those ways of life are stitched into every seam. Many of the garments highlight the penniless state of their makers – four of the Bowery pieces, while flawless in their construction, are all made from the same two cheap bits of fabric: a cheery striped cotton and a silver lamé, recycled and reworked on each piece as the edging on a jacket or the patched star detail on the front of a coat. They both show the way Bowery worked like a fashion designer, even though he didn’t show like one. ‘‘All of the outfits would have a course to run,” explains Philip. “And then we’d all be waiting for the next quarter – the next instalment. It was actually almost like a mini fashion show with Leigh. You knew there were four looks every year.” And then, the carefree way he wore his clothing; staining, tearing and ripping them as he danced and performed. The hooded cape designed for Michael Clark that Jones has just acquired shows this particularly poetically – the inside of the eye slits are still caked in thick black kohl, while the gusset is stained with sweat.

Today, Jones has given up on eBay. Partly because it takes up too much of his time, and partly because now so many people know about his work they come straight to him. Alongside swapping Galliano in exchange for Bowery or Westwood with Philip like Pokémon cards – “just with higher stakes” – he’s acquired several pieces from former revellers like Sue Tilley. So why do people trust Jones with their memories? “Sometimes, when you build something up and you’ve had everything and you’ve seen everything, it’s good to knock it down and start again with something else,” explains Philip, who sold Jones most of his Westwood and Bowery collections. “I started collecting John Galliano and I became obsessed by it. I started collecting all the early stuff and I now have 125 pieces, probably the biggest collection of Galliano. Before it was the Westwood thing and the Leigh thing. I had fun with that. I had 20 odd years with it. But now Kim is, if you like, holding up the torch for the younger generation. When I gave it to him I knew that it would be going to a good home and I knew it would be filling magazines and museums. And that was really important for me, for somebody like Kim Jones to have the best of everything and to show people it. I could have sold it to clients in America for even more. But it wasn’t about that. The pieces are almost like your children, you know. And they are quite precious and you want the youth of today, you want people who are interested, to see how good this whole period was and how interesting it was.”

It’s a similar story for Tilley, a dear friend of Bowery’s, who’s given Jones several pieces that were made especially for her. She learnt of Jones after he “stole” her friend’s job at Dunhill – Jones served as Creative Director there from 2008 to 2010 – and added her on Facebook. A couple of chance meetings in the street later – “he always recognised me rather than me recognising him” – and the two hit it off. In a gesture that is symbolic of Jones’s innate generosity, he flew Tilley to Paris for one of his Vuitton shows and invited her to several events at his home. Now they’re working on a book together of all of the postcards Bowery sent Tilley. Her trust in Jones explains why she’s happy to part with gifts from such a close friend. “I loved my youth. I truly loved it. It was fantastic, but I’ve written about it, I’ve talked about it. I don’t like to live in the past. I like to move on with new adventures and excitement. I’m thrilled I was there. But I’m not a sentimental person so I’m happy to give away. What’s the point of me having it? It’s just all tatters, at least Kim can look after it,” she says. It’s an ethos Jones understands given how many of the set were affected by AIDS: “Imagine seeing your friends dying. You’d have to start a new life, really. Those memories are nice but they’re sad.” That perhaps explains why so many of the set have let go of their collections. Rachel Auburn, for example, who worked so closely with Bowery that their ethos and design approaches became totally entwined, has kept none of her own work. Jones is sensitive to this. He’s adamant he’d give it all back to Auburn in a second if she asked for it. Same with Westwood. “If Vivienne asked me for something I wouldn’t sell it to her, I’d give it to her,” he explains. “At the end of the day, they’re hers – she owns the clothes.” He’s not bluffing. After Christopher Nemeth (3) died in 2010 Jones tirelessly photographed all of the collection to send to Nemeth’s widow to see if she wanted any of it.

While Tilley may not look to the past, one can’t help but wonder if nostalgia lies behind Jones’s collecting. The second time we meet is at his menswear show in Paris. Straight after the show we go to the Vuitton headquarters to go through the newest additions to the collection in person. As we chat, he flicks through social media with his team to determine responses to the catwalk show. Straight away conversations start about what will sell. Who will buy what? Are the LVMH bosses happy? As we sit and ponder, surrounded by LV wares, I see the incongruous bits of clubwear that surround us as a sort of escapism. They remind Jones of a simpler time, a sentiment Philip shares. “People didn’t buy 32 pairs of Jimmy Choos and Louboutins. People didn’t have 16 pairs of sunglasses. People didn’t have 22 dresses. They just didn’t. They had these clothes to go out and have fun with. They wore these clothes. When you got a piece of Westwood or whatever, you wore it four times a week. Yves Saint Laurent and Dior weren’t in vogue for young people. They were Knightsbridge ladies’ labels,” he explains. “But then these big companies thought, ‘well, we’d better get the young crowd in’. Now everything’s a bit corporate and controlled. And everything’s disposable.” I don’t want to put Jones on the spot, but note to him that it’s intriguing that the pace of his collecting ramped up as he grew in success and got deeper and deeper into the fashion system. “Our path in fashion at the moment is incredibly demanding. It’s kind of enviable to be a true artist and just get on with stuff,” he says finally.

Jones is not precious. He’s not an egoist or a miser. And while he’d like to see the collection out of the ugly plastic and in “beautiful cedarlined cupboards with glass doors”, he’s not keeping these pieces for his own fun. He’s also not doing it for pats on the back, and he’s certainly not doing it to make money – aside from upgrades, he’s only sold one piece, a Westwood parachute shirt; “I still regret it, but it funded my whole first collection. I had to do it.” He’s doing it so people can see it, a firm contrast from the tightly policed, inaccessible way luxury brands run their archives, to the point where sometimes even their own designers can’t access them – an issue you wonder if Jones faces at Vuitton. “I call my collection a working archive – I’m doing it so the next generation can access it,” he says. That explains why he’s not difficult about lending or sharing the pieces. Numerous friends from the industry have been allowed to inspect or admire them – “When he was at Vuitton, Marc [Jacobs] used to pop in quite a lot” – and on special occasions friends have been permitted to wear them at events. “Kate Moss has an amazing Rachel Auburn dress that I let her wear to a party,” he says.

“I actually need to get that back! I don’t mind lending it as lots of the things actually make girls look really hot.” Similarly, over the course of our conversation he donates a waistcoat from Galliano’s graduate collection to Central Saint Martins and, as he doesn’t want to hang on to Galliano pieces and Philip already has it, gives a jacket to a young journalist I tell him has just started collecting. Such is his enthusiasm for sharing, he encourages everyone who enters his Paris office to try on a Leigh Bowery hat that sits on the centre of his desk on a faux cheetah head to admire its joyful form and the innate skill behind its construction. Tilley understands Jones’s ethos. “It’s more clothes than art. It was only art when Leigh was wearing it,” she insists. Neither of them wants to see the pieces sat stiff and alone like stuffed animals. “I want it to be really alive. I have the idea of them being on big totem poles spinning so you can see the cloth in movement,” Jones muses. He’s lent bits of the collection out once – to the V&A for their recent Club to Catwalk exhibition – but has his sights set on a bigger, more comprehensive exhibition or book, for the benefit of students like those he spoke to at Central Saint Martins.

It was on that same Central Saint Martins visit that Jones came across a quote of his own that Louise Wilson had typed up, printed out and pinned on the wall as some kind of warning or advice to her students, a quote that since her death has been doing the rounds on Instagram: “We’ve got nothing to say and we’re saying it.” He laughs that he’d said it in exasperation; “I was with these kids and they were talking absolute crap on a shoot.” You wonder if it also sums up his attitude to much of the output of the modern industry – product; story-less, soulless product. By contrast, Bowery, Westwood and the like had lots to say and they said it, proudly. “They didn’t care what people thought. I love the idea of them coming out of a council flat in the East End of London and walking along looking like that. It was just so, so brave,” he says. While Jones is not regretful – why would he be? – you do get a sense of restlessness, of a spirit contained and boxed in by the nature of the times he works in. It’s that spirit that identifies with the ghosts that are present in his collection. To him, those clothes do have something to say – they speak Jones’s language, and, in return, he keeps them safe.

Footnotes

1. Leigh Bowery, an Australian-born performance artist, turned himself into a living work of art, collaborating with the likes of Michael Clark and artist Lucian Freud. His creations found an audience in nightclubs such as Taboo or on stage with his band Minty or fellow performer – and later wife – Nicola Bateman. He is one of a generation of creative stars who were wiped out by AIDS, though he famously said, “I don’t want to be remembered as a person with AIDS, I want to be remembered as a person with ideas.”

2. Jones only focuses on a few Vivienne Westwood collections; Native Americaninspired Savage, Buffalo or Nostalgia of Mud, all early 80s, which featured huge tattered skirts and sheepskin coats in muddy hues, and Witches. The latter, his favourite, was the final collaboration between McLaren and Westwood and featured prints by Keith Haring. “With Westwood, what I love is they’d reuse the patterns the next season. Pieces come up time and time again. So I have a skirt from Clint Eastwood and one from Buffalo that are actually the same,” says Jones.

3. The late Christopher Nemeth is Jones’s favourite designer. He graduated from Camberwell College of Arts and went on to found design collective and shop the House of Beauty & Culture with photographer Mark Lebon, stylist Judy Blame and shoemaker John Moore. Nemeth’s early clothes were all hand-sewn, made from salvaged materials, most famously discarded linen mailbags collected from the gutters and pavements of London. In the early 1990s he relocated to Toyko where he had an avid fan base.

The original article was published in AnOther Magazine A/W14.

Kim Jones will talk at the Dazed Fashion Forum on Saturday July 25. See here for tickets and more information.