She posed for Picasso, danced with Charlie Chaplin, and was a muse for Magritte and more: we take a masterclass in style, frivolity and courage from the iconic artist

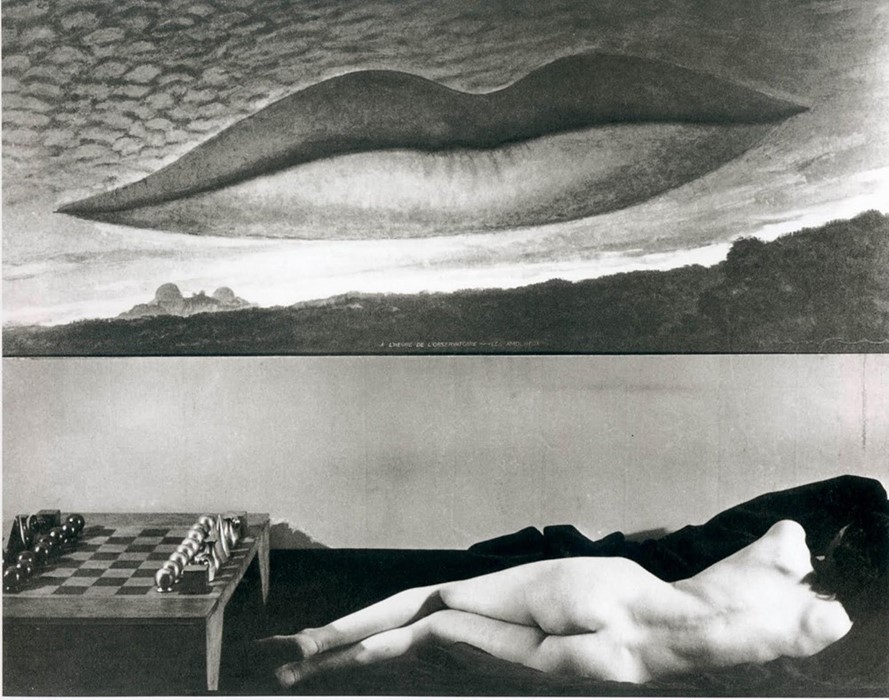

The life of photographer, model, muse, and Surrealist artist Lee Miller is so extraordinary that accounts often border on the fantastical. As a 19-year-old art student living in New York in 1927, Miller was almost killed when she stepped into oncoming traffic – she was rescued by none other than Condé Nast, the famed publisher. She left an impression. Months later, Miller appeared on the covers of both American and British Vogue. She went on to become a favorite model of photographer Edward Steichen, pose for Pablo Picasso, dance with Charlie Chaplin, and develop a foreboding photographic and artistic practice in her own right – studying under Man Ray and going on to shoot for British and French Vogue, and serve as one of the only female war correspondents during WWII. She documented the siege of St. Malo and brought Holocaust atrocities at Dachau to the American Vogue audience under the headline “Believe It.” She also visited and worked with Paris’ couture ateliers in the immediate aftermath of the war. The context of what the traditional fashion space could and should be meant little to Miller. She later moved to Cairo with a wealthy Egyptian man she met in Paris, left him to run back to Paris to marry Roland Penrose, and moved with him to the English countryside, capturing the likes of her fellow Surrealists and influencing the work of Rene Magritte, Jean Cocteau and others along the way.

It’s easy to place the artist in a sort of otherworldly category – after all, who lives this kind of life, especially today? But she was more than daring, and certainly more than lucky.

Here, we examine the lessons we can learn from Miller, from when to take a great risk to just how to give weight to our mistakes...

1. You decide when you want to be the object

It’s difficult to talk about the life of Miller without mentioning the early trauma that she endured. At age seven, she was raped by the son of family friends; she contracted a venereal disease and it took several years to physically recover. That said, Miller’s parents paired her with a psychologist who encouraged her to view sexual encounters and the inner life as separate entities – she started modelling nude in her father’s photography (a subject of great contention) a year later, and some have speculated that this distancing of the mind and body helped Miller to achieve the magnetic aloofness that lent such dignified grace to so many photographs.

She took ownership over her image – as a muse, as subject, through self-portraiture (her most famous photo may be the one of her nude in Hitler’s bathtub in his Munich apartment near the end of the war), and certainly, as the artist herself.

No doubt Miller’s vibrant life says a great deal about the endurance of the human spirit – but it’s also a testament to the ways in which we can dictate the statements we make. We are who we create ourselves to be.

2. No risk, no reward

It’s a cliché, but Miller lived it with enviable panache. When she was shown the work of forward-thinking surrealist Man Ray by her mentor Steichen, she ran away to Paris to find the famed American expat and work in his style. She arrived in Paris with letters of introduction in 1929, tracked down Ray, and declared herself “his new student.” When he told her he didn’t take on students, and would be leaving for holiday in Biarritz the next day as is, she simply said, “So am I.” The two went on to work together, travel together, and become lovers. She was his muse and student. But they also worked together to push the modern photographic form. Miller consistently asserted herself when it might have been easier to stay silent.

3. Mistakes can be golden!

It was with Man Ray that Miller accidently landed upon solarization. She left an image exposed for too long, and soon the pair went on to perfect the effect. There’s something to be said for taking a second look at perceived catastrophes.

4. Be a creative polymath

For anyone that has asserted that one can only do one thing truly well: counterargument – Lee Miller. She helped document the work of Schiaparelli and Chanel, starred in Jean Cocteau’s first film, and contributed work to Conde Nast‘s various international Vogues, serving as muse, time and time again, to the surrealists of her generation along the way. She simply sought out whatever adventure felt most essential.

5. Boundaries are what we believe them to be

Perhaps more than any other lesson left behind by Miller is the idea that we create, and are constantly at will to re-envision and define, the boundaries within which we work and live. The artist’s war reportage for American Vogue – sending back an image of a harshly burned GI in place of the expected nurses’ quarter shots; her willingness to head into battle, camera in hand; the way she documented post-war collections in Paris during a time when couture was less the focus; the way she shifted from muse to model to artist and back, again and again – there were very few lines that Miller did not transverse, both in her professional life and in her overlapping bohemian escapades. After a divorce from Penrose, there were affairs with Picasso, visits from Henry Moore and Miro, dinner parties with all pastel entrees arranged in Surrealist fashion, and still more adventures. Miller’s son, Antony Penrose, discovered 60,000 of her prints after her death in 1977. They were hidden in the family’s East Sussex attic. (Miller died of cancer, and told people who asked that, "she took a few pictures a long time ago.") It’s safe to say that even after death, she’s still breaking down assumptions by way of these (now published) pieces.