AnOther decodes Wim Wenders' cult classic. Expect melancholic moods, pink mohair jumpers and a cinematic score that swells with emotion

Wim Wenders’ film Paris, Texas is a painfully emotive exploration of existential grief, and a love letter not only to a broken romance but to America itself. Set to a bluesy soundtrack of Ry Cooder, there is a consistently aching melancholy to the film, which has become regarded as one of the most visually compelling narratives of all time. Set amidst sweeping desertscapes and seedy motels, there is an enduring beauty to its bleakness. Here, we consider the sartorial lessons we can learn from this cinematic classic: from its promotion of the humble baseball cap, to its famed fuchsia mohair sweater.

1. Americana is key

Growing up within the confines of West Germany, a young Wim Wenders found himself lost in the novels of William Percy, Mark Twain and William Faulkner, fantasising about the expanses that America could offer. “I read Faulkner before I ever set foot in America,” he explains in AnOther Magazine A/W15. “But he puts the South so vividly in front of your inner eye that you even smell it and feel the heat.”

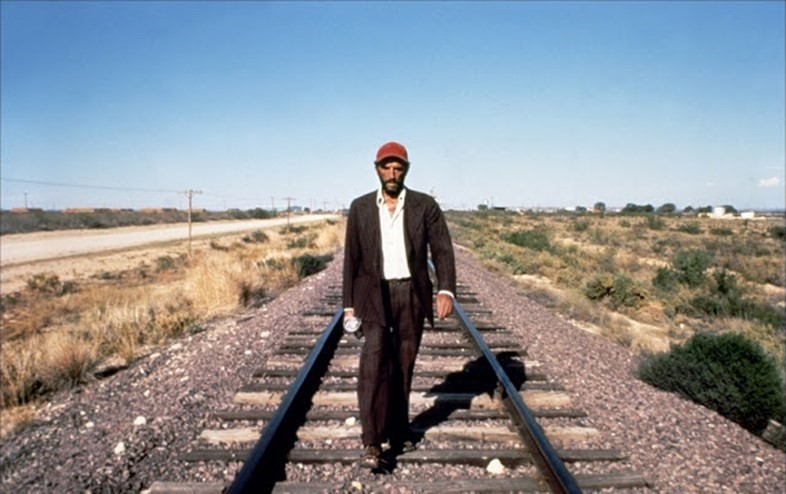

This passionate sense for heritage Americana permeates Wenders’ work – and particularly Paris, Texas, with shots lingering upon expanses of highways, diners and gas stations. This sense is also present within the wardrobes of his cast; Roger Ebert even described progaonist Travis’ first appearance in the film as depicting “the universal costume of America”. First appearing within the Southwestern desert wasteland in a threadbare suit, broken trainers and a red baseball cap, he is the quintessential everyman of the American dream, broken by the tale which subsequently unfolds.

2. A mohair sweater is a necessity

In spite of the constant appearance of beautiful landscape shots, perhaps the most iconic visual within Paris, Texas is of Nastassja Kinski (Jane) in her pink, mohair sweater. It is what she wears when she is first seen again by long-lost lover Travis, who has spent years wandering through a solitary purgatory trying to find her – and her drawling warmth is contrasted against the outfits worn by the previous peep-show hostesses he has trawled through in order to find her.

The divisive setup, which positions Jane behind one-way glass, places us in the same, voyeuristic position as her clients; our focus fixed on her pouting, pink lips, self-conscious gestures and large, sleepy eyes. She is the woman of his dreams and, slightly swamped by the loose fit of her dress, her back revealed by a swooping cutout, she is simultaneously sexual and chaste: not necessarily what one would expect from a peep-show attendant, but everything that Travis has been yearning for.

3. Blonde hair ought to radiate

When Travis visits Jane for the second time, he sits in the dark while, on the other side of the glass, her halo of golden blonde hair is spotlit into radiance through the fake window in her strange room. As he starts to explain the story of their relationship – she initially unaware of who is speaking to her – we watch her face change, shift into recognition, her eyes well up with tears.

As she starts to cry during his explanatory speech it is one of the most agonisingly emotive scenes ever captured on film; as Guy Lodge explains, “you’d call it a monologue if Kinski’s perfect face weren’t constantly responding to every scarring revelation” – and this close-focus makes it not only one of the most heart-wrenching moments in cinema, but also one of the most-referenced in beauty, her black-lined eyes and shadowed lids set against her luminous blonde hair now utterly iconic.

4. Slide-guitar riffs heighten the melancholic mood

Accompanied by Ry Cooder’s exceptionally melancholic slide-guitar (based on Blind Willie Johnson’s Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground), the film’s delicate yet powerful soundtrack is a key feature within the film – in fact, Wenders once said that the film was shot with a camera and a guitar, describing Cooder’s work as “sacred music”. Plucked notes reverberate into the landscape; pieces swell with emotion; Harry Dean Stanton himself sings mournfully in Spanish. It is cinematic score at its absolute finest.

5. Spoiler alert: not everything has to have a happy ending

While the film seeks to resolve Travis’ loss of Jane through his searching for (and finding) her, it still repeatedly deals with the theme of separation. To unite his son, Hunter with his mother, Jane, Travis must remove him from the care of his brother and sister-in-law who have been caring for him for four years. Additionally, and in perhaps the most poignant moment of the film, Travis must make the decision to leave both Hunter and Jane alone together so that they can build lives alone without him. Perhaps the most powerful element of the film is its reluctance to cleanly resolve any sense of sadness, but rather its preparedness to finish without a happy ending: at the close of the film, Travis is left as the solitary wanderer who first arrives on our screens.