AnOther traces the sartorial significance of female Afrofuturist artists – from AfriCOBRA to Janelle Monae and Grace Jones

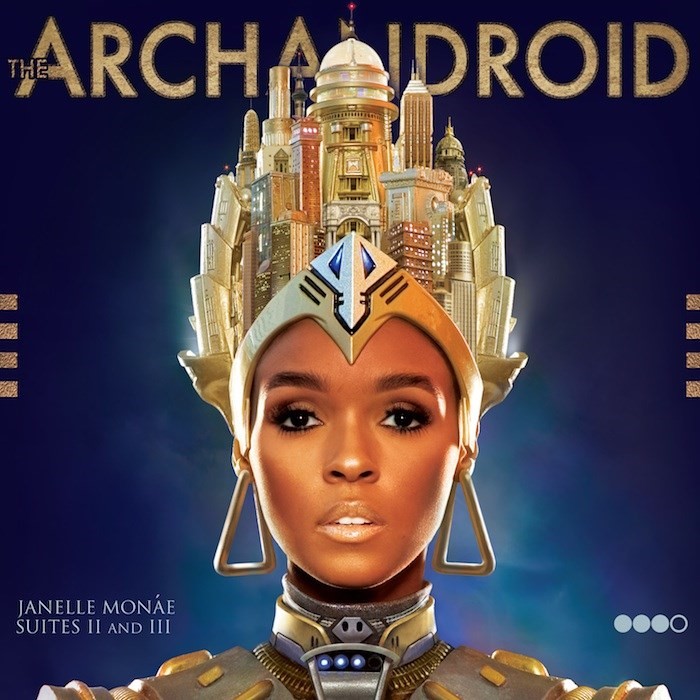

“The apocalypse has already happened. The aliens came,” said U.S. Professor Valorie Thomas. The aliens came in their ships for the Africans, abducted them, subjected them to experiments, and took them to an unknown place, cruelly – and ironically – rendering them alien themselves. By defining themselves with sci-fi language – “I’m not man” said cosmic jazz musician and Afrofuturist pioneer Sun Ra – “I am half android,” declares pop and R&B singer Janelle Monáe – Afrofuturists develop new identities of their own creation instead of those bestowed upon them by a society that defined them as subordinate. Monáe’s android, according to Thomas, is “the android other figure in society, and so she’s playing with that idea and what it means to rearticulate the body that has been dissected, that has been mutated and that has been made to perform.”

The term Afrofuturism might only have been coined in 1993 by author Mark Dery, but the black cultural experience of freedom achieved through sci-fi, ancient African cosmology and magical realism has been underway since the middle of 20th century. Time, for an Afrofuturist, is a fluid concept, and the terms past, present and future aren’t necessarily linear. Some of the historical moments at the roots of Afrofuturism have cycled back into relevance with heightened urgency today. Underpinning Afrofuturism is African diaspora, the displacement of people from Africa due to the slave trade. The question of how people define others as equally or less human – and subsequently treat them according their geographical origins, could not be more relevant to today’s international migration situation.

Constructing new identities

The “survival tactic of shape-shifting,” as Curator Ingrid LaFleur puts it, occupies a key place in Afrofuturism creativity. It’s present in the work of ‘android’ pop star Janelle Monáe, and Detroit artist Krista Franklin – whose 2007 collage work SEED (The Book of Eve) saw Franklin drawing on the cover of novel Wild Seed, where the young female protagonist takes on powerful identities, such as a white man or a lion, to navigate a hostile world.

The practice harks way back to the AfriCOBRA collective of the 1960s and 70s, which sought to empower black communities through forging a new self-defined visual identity. One of the most important of its works was Jae Jarrell’s Revolutionary Suit (1970) – a two-piece suit, accessorised with a sewn-in ammunition belt. This outfit appeared in Jae’s Husband Wadsworth Jarrell’s painting Revolutionary (1971), a portrait of political activist Angela Davis wearing the pink tweed, ammo-adorned garment. Speaking earlier this year Jae Jarrell said, “One of the tenets of AfriCOBRA was to reinvent yourself.”

Reclaiming tradition

While looking towards a space-age future, Afrofuturism is simultaneously deeply connected to ancient African tradition. In Chicago Art Magazine, scholar and artist D. Denenge Akpem writes: “In Afro-Futurism, the garment is an active part of the creative/transformative process; the garment or costume is an activator. In West Africa, for those Egungun priests who invoke the departed spirits, the self disappears in the wearing of the sacred garment; one becomes a vessel for spirit.”

In the same article, Akpem explores this in the context of contemporary sculptor Chakaia Booker: “Always pictured in her headdress of African textiles, wrapped one on top of the other with panels hanging to shoulder and sometimes waist-length, she is Amazonian with eyes so direct they seem to strip away all pretence. Her presence is awesome and beautiful. Her monumental works of discarded tire rubber speak to reclamation and reuse; she pushes the material into forms that are alive, organic.”

Afrofuturist women in Pop

The ultimate medium for channelling a highly stylized alter-ego, pop music has always been a platform for presenting a self-created identity to the world, but many African American female artists have presented their pop star personas with uniquely Afrofurutist codes: a mixture of ancient African spirituality and space-age technology. It’s arguably present in a lot of 90s and 00s R‘n’B music videos: trio TLC’s classic No Scrubs, where the girls champion android-like technological attachments on their cyber punk-patent cargo trousers aboard a futuristic set; or in the late Aaliyah’s video for We Need a Resolution, which sees the singer levitating (a motif also employed by Janelle Monáe in the video for her 2015 track, Yoga).

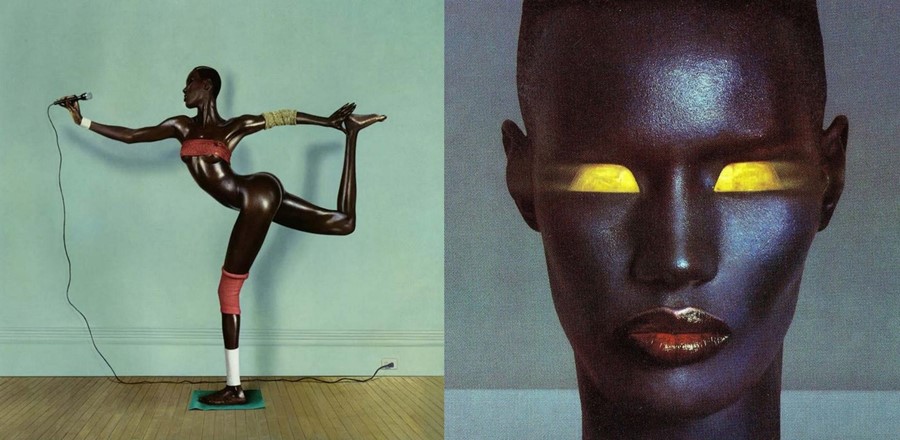

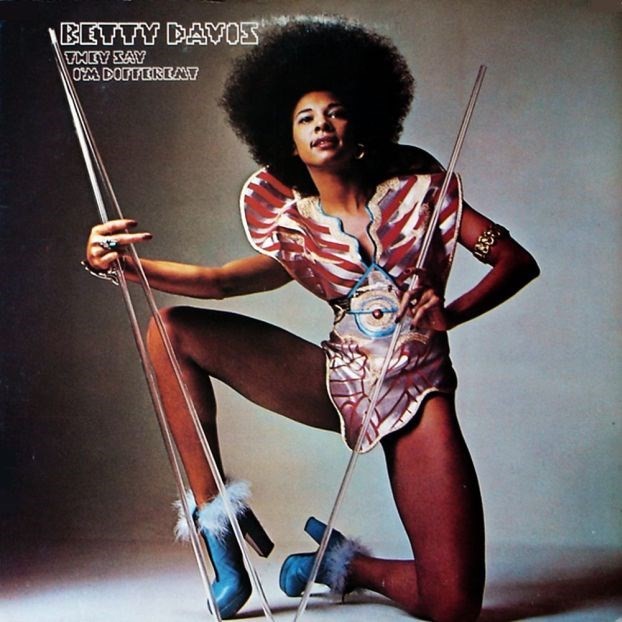

Pre-dating them by several decades, Betty Davis sang “They say I’m different ‘cause I’m a piece of sugar cane; My great grandma didn’t like the foxtrot; Nah, instead she’d spit her snuff and boogie to Elmore James.” So core to her message was this song that it became the title to her self-produced 1974 album on which the track appeared, the art for which featured Davis in a costume part afro-mysticism, part glam rock. And then, of course, there is the inimitable Grace Jones, who proclaimed “I wasn’t born this way. One creates oneself.” With her almost mechanically angular hair-cut and gleaming make-up turning her dark skin metallic, a look she’d play up to with avant-garde stage get-ups and experimental photo shoots, she was an embodiment of not only the transformative power of pop music, but of the uniquely feminine perspective on black culture that Afrofuturism allows.