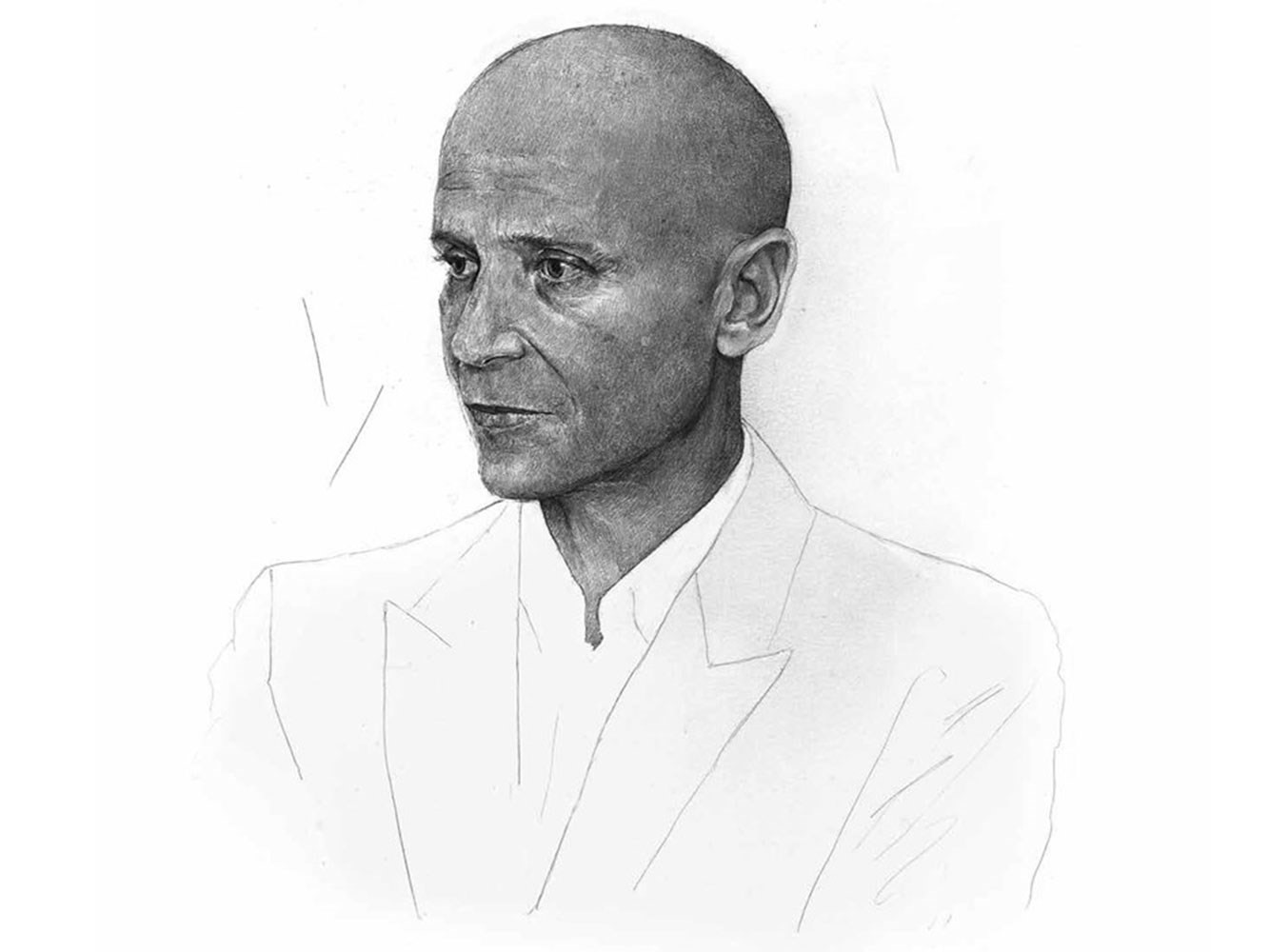

Adrian Joffe briskly walks into the long, quiet space that acts as Comme des Garçons’ showroom in their Place Vendôme headquarters. He reaches his destination, the chair on the other side of the room, in a split second and exudes the Zen Buddhism he practises. His involvement with the four-decade old anti-fashion powerhouse started in 1987, when the South-African self-taught businessman became a Paris-based commercial director for Comme after having travelled through Asia following his Japanese and Tibetan Culture studies at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies. He married the brand’s founder Rei Kawakubo in 1992, and became president of the company in 1993.

He was present at the birth of the world’s coolest department store, Dover Street Market in London, and its subsequent branches in New York, Tokyo, and Beijing. Joffe has many dealings, which include a peculiar perfume empire featuring gasoline scents and various deals with the thirteen lines designed by Kawakubo, as well as four sub-brands with lines run entirely by other in-house designers. That’s not all – he has also pioneered the launch of guerrilla ‘anti-concept concept’ stores worldwide, and been instrumental in numerous design collaborations with brands such as Louis Vuitton, H&M and Nike.

With such a vast number of operations to oversee as well as acting as Kawakubo’s translator and spokesperson, one could expect a CEO of his calibre to be rigorous. Expectations rarely turn out the way they are imagined.

Joffe comes across as warm, kind and calm. He asks questions in return to the questions that are being asked. With a genuine interest he investigates what today’s youth think, do, and how they can help. He speaks in a tone as calm as the room, in which two interns work at the very end. He proposes to drink coffee, and a bowl of biscuits stands between us. They remain untouched, and as the conversation ends, in which the definition of cool is discussed alongside the inability to understand sales, one of the interns brings two red rolls of fabric to the table and asks which one is more Russian. Adrian jokes, “Let’s get this on recording: for our Russian designer Gosha Rubchinskiy, let’s go for a little less communist and a nicer colour.”

We seem to live in a time where young brands have big social media followings and cool kids modelling their clothes, but the garments are just T-shirts with a big word on it. What are your thoughts? Is it more important to focus on quality, cut, and novelty of design, or social media hype?

I understand that it’s easy to be distracted and to be confused, and I think it’s the fault of Instagram and social media. It’s too quick, quick, quick. Everybody wants to be famous quickly. I think it is a genuine concern, but what advice can I give, because it’s how people do succeed these days.

Do you think the product is still important?

The product is definitely important – it’s about the quality and the staying power. What do you want? Do you want to make a quick fix, get famous and then do the real thing? It’s very hard. I don’t know what to say because I think it’s really important to have a concept and a vision and concentrate on the clothes. Keep the quality. Tell the story. If you have to use social media to tell that story, it’s a very useful tool, but you can’t just do that. It’s really about the whole thing and there has to be substance for it to last. It can’t just be the surface. A brand like Palace, for instance, does a lot with social media; good images. It’s simple but good things. There, the quality is good and the idea is good, even though it’s just a T-shirt like Supreme. It’s even becoming a competitor of Supreme. The guy from Palace opened his shop, shares his space with some other people; he’s buying some other brands. You know, that kind of all-inclusive way of doing things, I think it’s very modern. He’s got a proper concept, he has a vision that he has been working on for a long time, and he uses social media very cleverly. The product might be simple in its nature, but it’s substantial and it’s good quality.

"Tell the story. If you have to use social media to tell that story, it’s a very useful tool, but you can’t just do that." - Adrian Joffe

It’s almost as if the vision of the brand has become the product.

It’s part of the product – it’s part of the whole thing. What I’m trying to say is that it has to be the total, global thing, and it all has to be important. You can’t ignore or deny the power of social media, unless you really have a lot of patience and do things really slowly. That in itself could be another part of the product – it could be another way of doing it – but I think it’s just harder these days to really be in the background. Keeping it secret and doing it through word-of-mouth is one way, but even that is still part of the whole story. I think you have to find out which way is good for you, but social media can never be the whole story. It can only be part of the story. You have to use all the things available at your fingertips. You might as well use and understand everything available and try to make it a whole. I think that’s what’s important.

You’re in an amazing position where you run a brand, but you also have Dover Street Market, meaning you buy designers and meet customers. When you buy into a brand – from somebody who is very young, or to an established fashion house – are you checking their social following? Do you care?

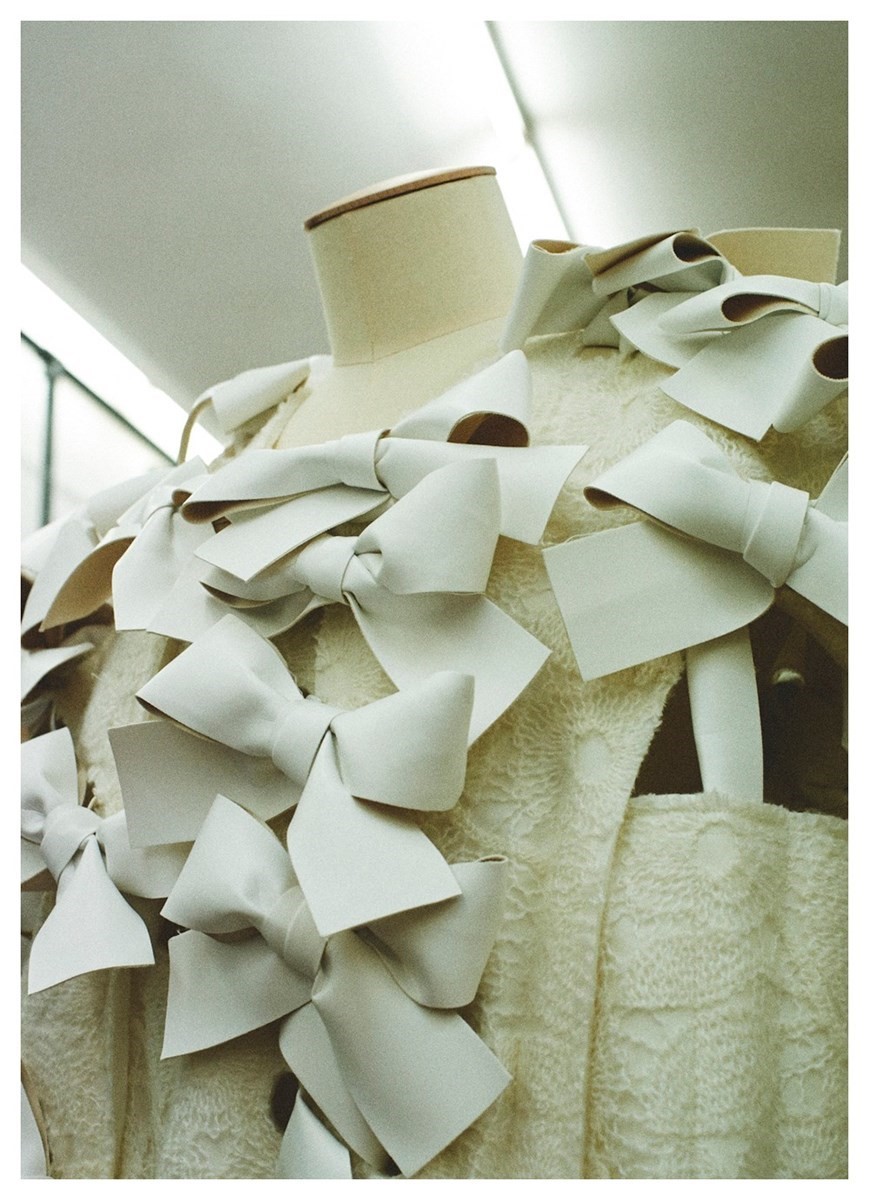

No, I don’t care. We like things that are sometimes under the radar. For us, going back to the beginning, the product is the most important. We can’t deceive the customers. We can’t buy rubbish just because everybody’s talking about it. We do look at the quality, and the nature of the product. It’s most important, but again, it can’t only be that. Like with Rei and Comme des Garçons: it was always the whole thing. When she was making a dress, she was already envisaging how it was going to look hanging on a rail in a shop six months later and how she was going to do the graphic design. In those days, there was no social media, but we did it in our way at the time.

What do you think is more important: cool or luxury?

Cool. Cool luxury. But what is cool and who decides what it is? The problem is that sometimes somebody decides what is cool but it’s not cool. Is cool a natural thing? Does it happen? Who decides? Who is the arbiter of cool? I think it happens organically and it’s not anybody who decides. I think the people who know what’s cool aren’t the people who are in charge. That’s the problem, isn’t it? But… maybe they can’t be in charge if they are cool.

"I think the people who know what’s cool aren’t the people who are in charge. That’s the problem, isn’t it?" - Adrian Joffe

Do you think that ‘coolness’ is a disease of fashion? You have a great product and two months later it’s uncool. Related to that are sales – I don’t understand why a product should go on 70% sale a few months after it’s been made, when it’s a beautiful, great design, and has impeccable finishings.

Sales are terrible. It’s the business: it’s all about the next thing, schedules… Everybody does these shows for pre-collections now. It’s crazy, all that stuff. That’s what’s not cool. I remember once, there were two deliveries: January and February, and nothing after that. Then people come to the store in January and February, and they don’t come again. It becomes boring. So I have always tried to not care about having all deliveries in that time. In Japan, the shops are changing all the time. It’s an incredible amount of work, but that’s what’s important. The people want to come back and see what’s new, that’s how fashion should be. In Dover Street Market they get stimulated and inspired constantly, not just January and February, then a dead period, and then sales. It’s such a terrible system that the department stores and big groups have kind of decided on. I get new deliveries in May even if there will be sale two weeks later – we don’t put that stock on sale, but it’s hard to resist the pressure of all that. It’s hard to be independent, but you have to stick to your guns.

You’re famous for being forward-thinking, like changing the way you sell old stock in guerrilla stores. But you don’t use digital the way other people use it.

Rei doesn’t want the main line online, but she’s changing. She was very dubious and sceptical about it in the beginning because she likes contact with people, she likes the humanisation of selling. She really wants to try her best to protect that, so she has resisted online selling. They don’t have it at all in Japan. There is an e-shop for Dover Street Market Tokyo, but I can’t sell Play on it; I just sell wallets, perfume, a bit of Nike shoes. In London and New York she allows me to do shirts and things that aren’t collection brands, and then all the other brands. She says we’re not allowed to do that for the main brand. She won’t do it.

But other shops are selling it?

SSense is doing it very well. You know, we check how they do it, and I think you also can’t stop it. If you’ve sold something to a company, you can’t stop them from how they sell it. Once they’ve paid for the goods, they can do what they like and they can put it on a rack outside and sell it however they like. It becomes their property and I think legally you can’t really stop it. People do try and stop it. I kind of let it go. I wasn’t too worried about SSense, because you know, they sold well and it was good for the customer. It’s all over Canada and it’s a big country; they like to buy online. You’ve gotta support the new way, and I want to be forward-looking and do that. I have visions of how we can have an e-shop, eventually.

So it’s coming?

It’s coming…

Read the full piece in the new issue of 1Granary, available in stores and online from September 19, alongside features with Simone Rocha, Thomas Tait and more...