Dubbed the ‘petite saint of maverick writers’ by Patti Smith, we celebrate Albertine Sarrazin, whose life story is as intriguing as the electric prose of her cult novel, Astragal

If it wasn’t true, one could levy charges of melodrama at Albertine Sarrazin’s life story; certainly, when it comes to author biographies, it’s hard to think of many that are more compelling. Born, and quickly abandoned, in Algeria in 1937, Sarrazin never knew the identity of her mother. Named Albertine Damien by social services, she was later baptised Anne-Marie by her adoptive family. Fiercely intelligent and naturally gifted, her childhood was rocked in the cruellest way when she was raped, aged ten, by a member of her stepfather’s family. Following Sarrazin’s attempts to run away she was enrolled into a miserable girls’ reform school. Eventually she escaped from there, slipping into a shadowy Parisian world of petty crime and prostitution. Arrested at 18, she was given seven years in jail for armed robbery; in 1963 she was sentenced to another four months for stealing a bottle of whisky. And throughout all this, the vivacious Sarrazin wrote and wrote and wrote.

Sarrazin’s most famous work, the semi-autobiographical novel Astragal, follows the 19-year old Anne’s travails through some of the dingier corners of Parisian society, erstwhile lover and habitual criminal Julien by her side. From the opening scene – when Anne jumps 30-feet to escape from prison, breaking her ankle in the process (the ‘astragal’ from which the title takes its name) – the agenda is set. The text is as unruly as its author and narrator, the effervescent prose fizzing with the vitality of youth, ricocheting around the page and refusing to be penned in. Sarrazin’s words are so alive that they dance and fidget on the page, and one wants to consume them with an almost narcotic urgency. Despite the potentially depressing subject, the low-life milieus are punctuated with sardonic humour, elevating poetry and cutting observations ("I had escaped near Easter but nothing was rising from the dead," how’s that for an impeccable turn of phrase?). Astragal is a touching treatise to youth, the redemption of love found in unlikely circumstances and the grace that can be found in the grime.

Defining Features

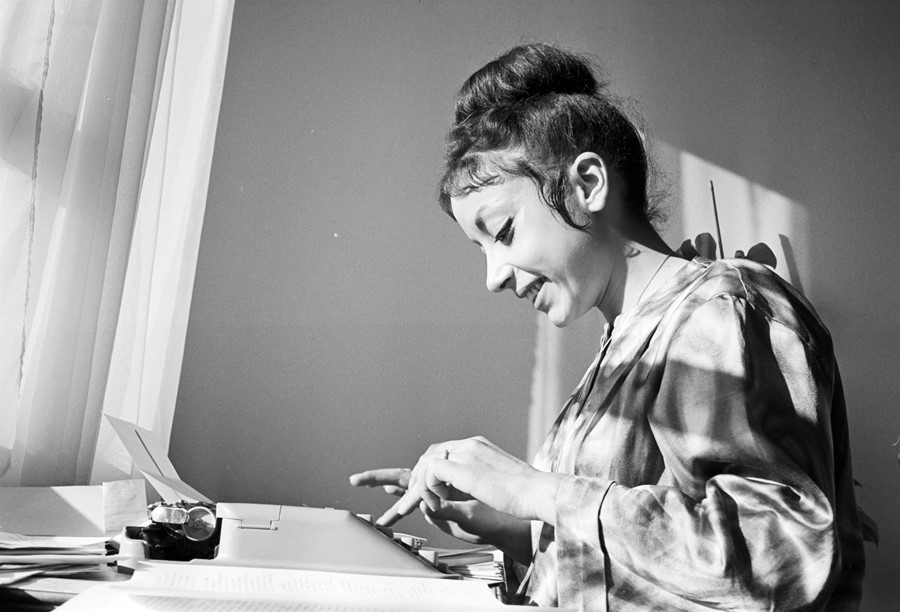

The petite Sarrazin had a toughness and fiery spirit that belied her diminutive stature. You can see it in the wry, knowing smile – sometimes a smirk – lipsticked on her face; she’s in on the joke all the way. From a purely aesthetic perspective, if you’re looking for a new Beat-generation pin-up, Sarrazin ticks all the boxes: dark hair cut into a pixyish style (sometimes cropped, sometimes piled high in a bun with a scraggly fringe framing her youthful face), black eyes lined into feline flicks, vintage furs and, of course, a fug of Gauloises smoke snaking up around her. Sarrazin epitomises dishevelled glamour, here’s a woman who despite the trials of her life clearly took a certain joy in her appearance – sometimes to her detriment; her notebook was confiscated in that reform school when her Lily of the Valley perfume was deemed too strong.

Seminal Moments…

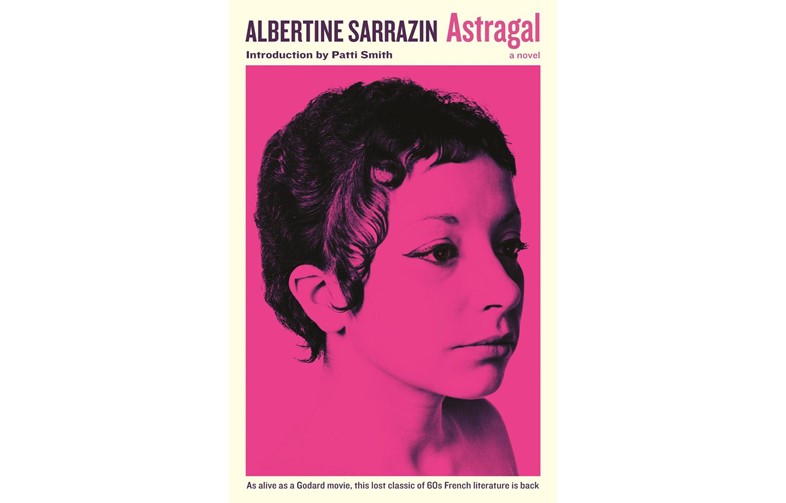

Sadly, perhaps Sarrazin’s seminal moment came just a year after her death in 1968 (she died at just 29 from complications during kidney surgery), when a 22-year old Patti Smith chanced upon a copy of Astragal in a Greenwich Village bookstore. Drawn to the cover proclaiming Sarrazin the "female Genet" ("The female Genet? She is herself", Smith responds to that in her touching introduction to an Astragal reissue) and utterly seduced by the first few lines, Smith – then in the clutches of one of those all consuming but futureless love affairs – was instantly hooked on the French writer’s words. Astragal went on to acquire on almost talismanic power for Smith, who carried a copy of the book on her person for decades.

"I truly wonder if I would have become as I am without her" - Patti Smith

In recent years, Smith has helped propel Sarrazin and Astragal to the profile they deserve, and her sensitive dedication to the book is a reminder of the youthful joy of discovering a writer, singer or artist who you feel is looking directly into your soul and speaking to you alone. For the young American, the dead French girl’s words helped fuel her own artistry. "Perhaps it is wrong to speak of oneself while writing of another, but I truly wonder if I would have become as I am without her," writes Smith in the introduction. "Would I have carried myself with the same swagger, or faced adversity with such feminine resolve, without Albertine as my guide? Would my young poems have possessed such a biting tongue without Astragal as my guidebook?" It’s fascinating to think who else may have had this effect on.

She’s AnOther Woman because…

While life circumstances are most probably wildly different, it’s impossible for any strong, independent woman not to see some mirror image of herself in Anne/Albertine and feel a certain camaraderie towards them. Sarrazin’s independence is empowering (note for instance the young Anne’s dismissal of one of her clients, "The poor thing, he wanted to give me pleasure!" – hers is never a victim-narrative). Through her writing, she reminds us that captivating, forceful and, yes, beautiful art can spring out of the most desolate of circumstances. And in touching us, it reminds us of the universality of the human experience, that we read to know we are not alone. There’s a sisterhood and comfort to be found in Sarrazin’s work, as Smith again puts it, "my own words were not enough; only another’s could transform misery into inspiration." “Forget about meeting me,” Anne tells her soon to be lover Julien at the beginning of the Astragal, but just as he won’t, we’re unable to forget Sarrazin too.