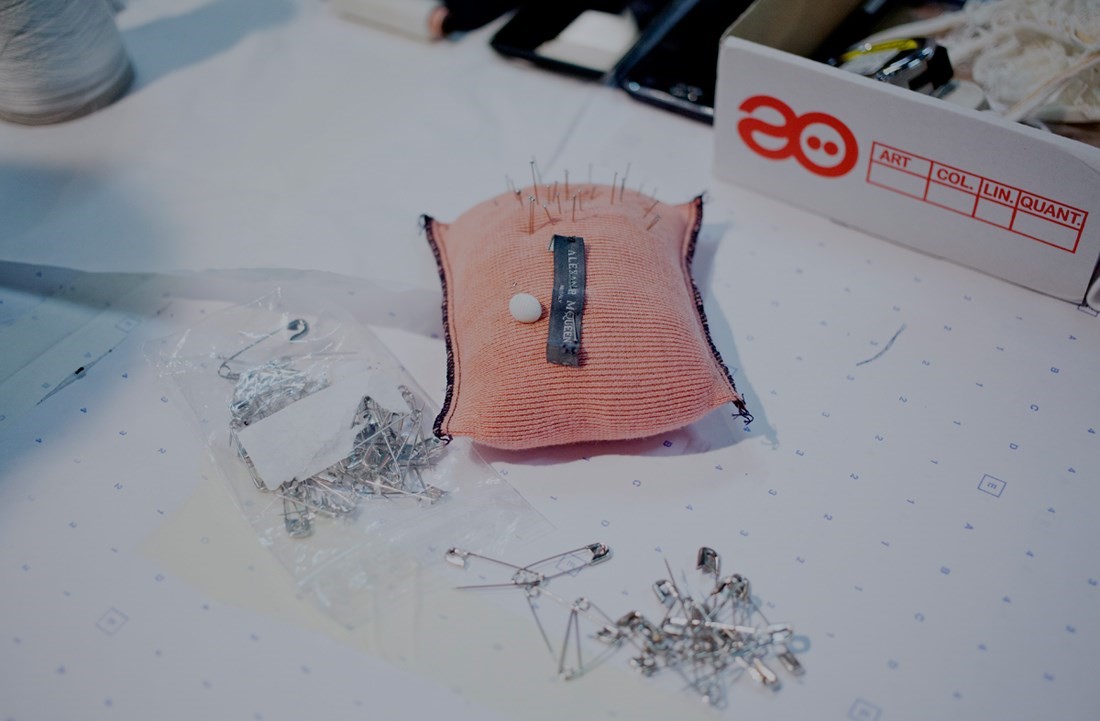

It’s a little under a week before the Alexander McQueen Spring/Summer 2016 collection will be shown in Paris and the house’s creative director, Sarah Burton, is in fittings. The bright, white studio on the top floor of the Clerkenwell building that is the company’s HQ is filled with mood boards, fabric swatches, the miniature paper doll models that Burton likes to work with so that she can study the three-dimensional effect of designs and, of course, both toiles and soon-to-be-finished show pieces.

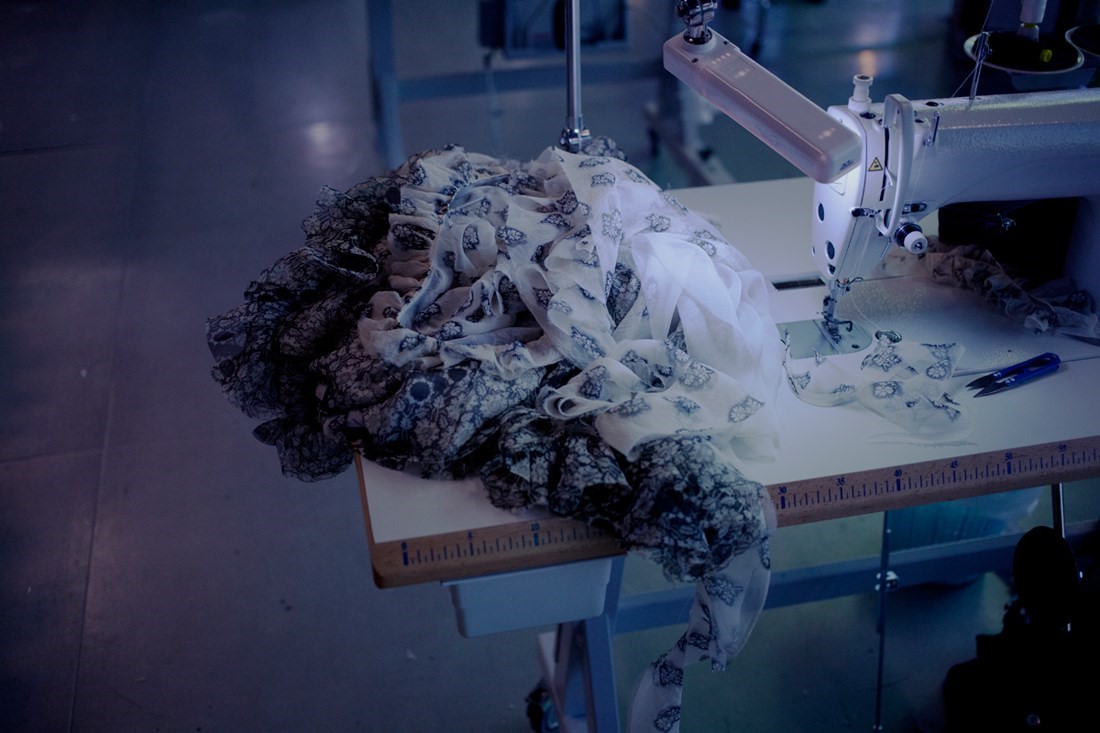

"I like the idea of weavers, it’s very craft again," she says of the line that's soon to be presented on the runway. "Everything is soft and washed. The silhouette is narrow. It’s almost like the stuffing has been knocked out of her." In fact, Burton’s almost obsessive attention to craft – to hand workmanship and fabrication – has always underpinned her work, both with and without Lee Alexander McQueen’s own presence. However, there’s a gentleness to this latest offering: to a ruffled chiffon dress with hand-massaged edges, to narrowly cut palest grey leather embroidered with flowers in an only very slightly lighter shade and so discreet that, blink, and you might miss it.

A Delicate Armour

The starting point for the collection was the Spitalfield Weavers, she explains, Huguenot migrants and religious refugees who arrived in England in the late 17th century and settled on the outskirts of the City of London. "Before they came from France, they arrived from the Netherlands," Burton says. "They didn’t have any money, but they brought flower bulbs in their pockets and planted their own gardens. There’s something very beautiful about that." Beautiful, yes – and extremely romantic.

There is also clearly a reference to No.13, McQueen’s seminal Spring/Summer 1999 collection and famously Burton’s friend and predecessor’s favourite show at play. That, of course, was his most unbridled homage to the arts and crafts tradition which he too was always both indebted to and inspired by. Lee McQueen’s woman was fierce, however: a play between power and fragility, innocence and experience, light and darkness, was a central tension to his work. Burton picks up the most exquisite chainmail vest, as fluid as liquid and as delicate as it is possible to imagine. "How do you make armour – which is a very McQueen thing – really soft?" she says, then pauses for thought before adding: "the collection is definitely all about women."

"How do you make armour – which is a very McQueen thing – really soft?" – Sarah Burton

The Exquisite Relaxation

As guests filed into the show only days later it was clear that a different, though evidently still respectful, sensibility was in the air. Gone was the centrally placed and principally square runway, in favour of a raw wooden floor with guests seated in narrowly arranged rows around which models would soon weave their way, enabling all invited to see the exquisite clothing up close. Less obviously high on drama, too, was lighting: relatively simple rigs had been erected overhead.

Soon, out they came in ultra-fine knit dresses, slashed and peeling away from their slender frames and falling in ruffles to the floor, in the most impeccably worked tiered lace worn over relaxed tailored trousers or under a cropped, crimson military jacket. There was denim, too, densely jewelled in rich rainbow colours and distressed, nappa leather designs that fell to the ankle and were finished with overblown blooms and a waterfall frill at their plunging neckline. The latter were a nod to several original Spitalfields silk court dresses woven with equally exotic flowers found by Burton and her team in the run up to the show. These precious antique pieces hung in the studio as they worked.

For all the loveliness of even the most apparently simple garment (a signature McQueen frock coat, say, quilted and frayed at the edges, only cut in this instance in crumpled white cotton) there was, it almost goes without saying, nothing even remotely minimal about this aesthetic. Instead, the paneling, shredding, engineering, silk and mirror embroidering and piecing together of hugely complex garments was achieved to a level that is unprecedented. As for the shoes… In place of the elaborate, sculpted and purposefully strange designs Alexander McQueen has long been known for were only slightly elevated clogs and even trainers. They were relaxed by this house’s standards for sure – "but still embroidered and inlaid, not basic at all," Burton laughs.

"They were relaxed by this house’s standards for sure – 'but still embroidered and inlaid, not basic at all,' Burton laughs"

A Loosening of Legacy

While Alexander McQueen himself was interested in transforming his models into almost anonymous creatures as far as high-impact hair and make-up was concerned, meanwhile ("it’s not about models’ feelings but about mine," he once said), this too had changed. With undone tresses and dewy skin girls here were both instantly recognizable and individual – ethereal and lovely for that. "I wanted them to look very natural," Burton says.

The values central to the Alexander McQueen name – a respect for tradition, for the skills of the ateliers, an interest in history and more – were all still in evidence, this did ultimately seem like a move forward for a designer who has worked hard and with great sensitivity to continue the house her mentor founded. "It’s loosened," is how Burton herself puts it. "I thought to myself: 'If it’s not believable then don’t do it, if it’s not believable for me, then I’m not putting it in.'" There was a sweetness and ease here, then, that seemed highly personal to this particular designer. "I wanted the girls to feel completely released, for them to be touchable and very, very feminine." Sarah Burton said, summing it up neatly backstage after the show.

"I wanted the girls to feel completely released, for them to be touchable and very, very feminine." – Sarah Burton