AnOther explores the life, style and enduring influence of iconic model, Dovima

“Sing in me, Muse, and through me tell the story,” wrote Homer in The Iliad and The Odyssey, invoking the divine inspiration of a muse, demonstrating just how ancient that tradition is of men searching for a creative light-bulb moment in a woman. In the fashion world, women with a certain je ne sais quoi have provided inspiration for collections, styles and imagery ever since the industry began. In the latter part of the 20th century, with the advent of the supermodel, these muses stepped out from under the gaze of their artist masters, and forged a name and identity of their own. However, without this blueprint, some of the early fashion industry muses are forever defined by the work of those they inspired, struggling to assert their independence outside of the work they created collaboratively.

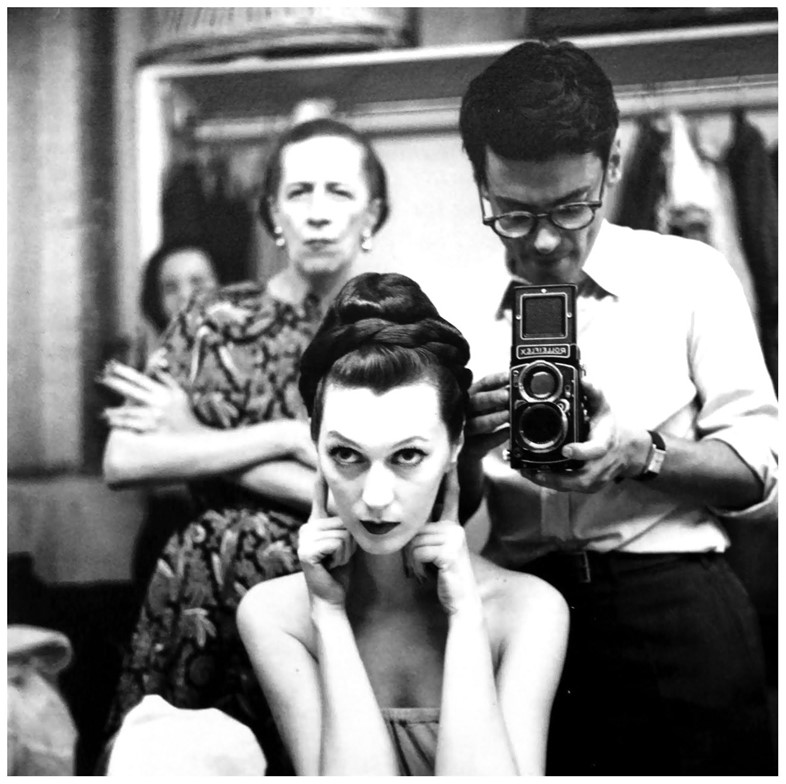

With a tiny waist and regal demeanour, Queens New York-born Dorothy Virginia Margaret Juba was the perfect model for the new silhouette of post-war America, totemic of a new era of aspiration. Following her discovery by a Vogue employee and her first shoot with none other than Irving Penn, she became a muse – and some-time lover – to photographer Richard Avedon, with the duo creating some of their most iconic shots together. Attempting to put her startling beauty into words, Avedon once described her in the following way: “The ideal of beauty then was the opposite of what it is now. It stood for an extension of the aristocratic view of women as ideals, of women as dreams, of women as almost surreal objects. Dovima fit that in her proportions.”

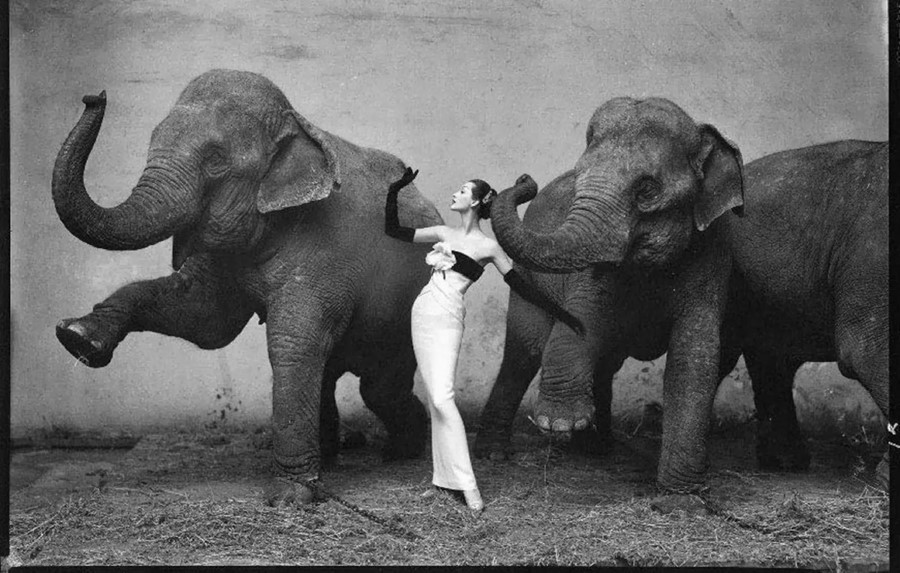

Iconic imagery

The muse, keen to go the extra mile for her artist, pushes the boundaries of an ordinary day’s work. Working in creative synergy, Avendon and Dovima created iconic work, and one of the most enduring images is the famous shot of Dovima with Elephants, which depicts the model elegantly arched in eveningwear between the two beautiful yet intimidating creatures. “The elephant shoot was the most terrifying moment for me because I had to just trust that things would turn out all right,” said Dovima. “But, oh, what a wonderful time! This was the moment where, as a true muse, I had to let go completely. It was my biggest decision as far as what I was willing to do in order to get the fame I wanted and needed.”

On just how significant the image has proven to be, fashion writer Annalisa Barbieri once declared, “To me [Dovima and the Elephants] typifies what fashion photography should be about… There are people that criticise fashion photography and say that it is not depicting reality, but I think it should always be inspirational and aspirational. I love the scale of this picture. I love the fact that she looks almost as tall as the elephants and the way the sash is done lends a very long line to her… Having also worked with animals in fashion photography I know that there must have been a crew of several dozen to actually control them and I wonder how many takes they must have used to get this picture right. I just love the sheer scale of it and I think if more people did things like this instead of the reality that is creeping into fashion photography, we’d have far more beautiful images to look at.”

Putty in their hands

In order to fulfil the artist’s vision, a muse becomes the object, and in doing so, as Dovima’s story attests, can seem to lose something of themselves. Describing the synthesis of the pair, Dorian Leigh said, “He used Dovima like a painter uses a medium. She was his medium.” It would seem as if this is something Dovima not only accepted but saw as an important role, one she gave her all to in order to fulfil. Dovima submitted to Avedon totally, opening herself up to becoming exactly what he required. She’d later describe her professional technique as becoming like “putty”, so elastic and completely malleable she would allow herself to be a devotion to Avedon, borne out of love as much as it was professional commitment.

Expiry date

Her relationship with Avedon over, Dovima retired from modelling in 1959, explaining, “I didn’t want to wait until the camera turned cruel.” In an interview with V Magazine, Lisa Fonssagrives asked Dovima if she felt abandoned by Avedon and the fashion industry. “Yes, of course,” replied Dovima; “I gave them everything they wanted and I didn’t have any more to give. In the end I was only a piece of business to Avedon, and the fashion industry had no use for an older woman beyond her prime!” It’s a sad fate that has met many a young, beautiful female muse. It happened with young artist Dora Maar, who made her mark on the surrealist movement, only to end up known only as a muse to Picasso – appearing in Portrait of Dora Maar and Weeping Woman. Once that relationship soured, Picasso moved on to another model, Françoise Gilot. Like Maar, Dovima’s life’s work is forever defined within the context of the male artist she inspired.