Inspired by the upcoming documentary, Little Girl Blue, AnOther celebrates the first lady of psychedelia

When Janis Joplin left the stage with her band, Big Brother and the Holding Company, at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, the impact she had had on her audience was tangible. “You know you got it if it makes you feel good,” she’d screamed soulfully into the microphone – a lyric which would come to symbolise her tragically short career – while ‘Mama’ Cass Elliot was caught on camera mouthing “wow, that’s heavy” as Joplin finished her set. She was already fully-formed star; stamping her gold lurex flares, and her vocals evoking chills even by proxy of low-quality YouTube clips watched back more than 50 years later. It was a legendary performance that launched her to stardom.

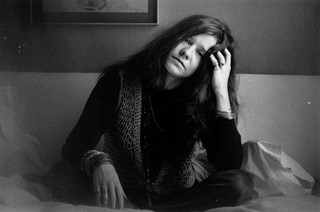

Joplin had escaped her oppressive, small-town Texas upbringing only a few years earlier. As an adolescent, she was bullied by her peers at school for not fitting in, and later was shunned by her segregationist society for her strong belief in racial equality. She turned instead to music, moving to Austin, Texas, where she collected Bessie Smith and Lead Belly records, but it wasn’t until an old friend set up Big Brother in summer 1966 that Janis began to sing professionally.

She moved to the then-burgeoning Haight Ashbury area of San Francisco. “I couldn't believe it, all that rhythm and power," she said, later. "I got stoned just feeling it, like it was the best dope in the world. It was so sensual, so vibrant, loud, crazy. I couldn't stay still.” Big Brother’s ascent was rapid. The album that followed Monterey Pop in 1968, titled Cheap Thrills, is still considered one of the greatest psychedelic records ever created, while Joplin continued to create an album for each remaining year of her short life.

Defining Features…

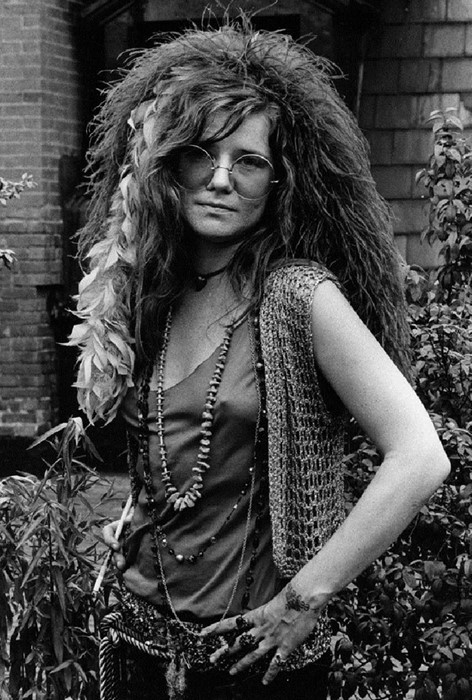

In her style, Joplin was paradigmatic of the 1960s. She favoured woven waistcoats, embroidered flares, strings of brightly coloured beads and voluminous bell sleeves, often sporting them all simultaneously. When her rebellious mane of frizzy red hair wasn’t big enough, she affixed an assortment of feather boas to it and let them swish wildly about her shoulders like bird of paradise. She painted her car, a 1965 Porsche Cabriolet, with butterflies and swirls, to match her outfits. The Southern Comfort distillery even apparently gifted her a fur coat to thank her for the publicity she gave them by drinking her favourite liquor from the bottle at her shows.

None of the 60s preferred quaint adjectives would fit Joplin, and so when she came to the attention of Vogue in 1968, she was declared “the most staggering leading woman in rock,” by the title instead. “Janis Joplin can sing the chic off any listener,” the magazine announced – rejecting its usual measure of success for a greater one.

Seminal Moments…

The singer, whose back and forth with the audience at her energy-fuelled shows possessed an irrepressibly sensual undertone, combined a fearless embrace of her own sexuality with a defiance of others’ rebuttal of it. When interviewer Howard Smith asked her about her rejection by the Women’s Liberation Movement, the response was staunchly non-submissive. “I’m representing everything they said they want,” she told him. “You’re only as much as you settle for. If they settle for being somebody’s dishwasher that’s their own fucking problem. If you don’t settle for that and you keep fighting it, you know, you’ll end up anything you want to be. How can they attack me? I’m just doing what I wanted to and what feels right and not settling for bullshit and it worked.”

She’s AnOther Woman because…

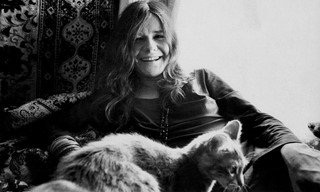

In spite of being riddled with her own insecurities, Joplin paired a raw and awe-inspiring talent with an uncompromising belief in the power of the music she made. When she died tragically from a heroin overdose at the premature age of 27, she left behind her a legacy of revolution and defiance, and a path for the women who would follow her. “She would stand before her audience, microphone in hand, long red hair flailing, her raspy voice shrieking in rock mutations of black country blues,” her New York Times obituary stated on October 5, 1970. “Pellets of sweat flew from her contorted face and glittered in the beam of footlights. Janis Joplin sang with more than her voice. Her involvement was total.”

Janis Joplin: Little Girl Blue, directed by Amy Berg, is showing as part of London Film Festival ahead of its release in November 2015.