From Beatlemania to Sociality Barbie, AnOther charts the cultural phenomenon of the fashion influencer

Just as teen culture emerged in the 1950s and 60s, the newly formed art of advertising also came of age. Wild adolescents and the recently-invented 'teenagers' bought into a new lifestyle, defined by a new way of dressing and sound-tracked by music that struck a dischord with the traditional values of their parents. The advertisers were ready to not only market to this fledgling demographic, but also tried to tap into their elusive currency of cool in the hope that some of it would rub off onto their products. From then on, those with enough of a cachet to be deemed a tastemaker could cash in if they chose to leverage their status. These days, this phenomenon is manifested through the international party girl thanking a brand for her new handbag, or a magazine namedropping which specific vodka brand made the cocktails at their fancy party. But, almost just as quickly as this marketing ploy has risen to peak saturation, so too did the cynical commentary from those attempting to lift the curtain on its artifice. Here, AnOther explores the discussion of the fashion influencer in art and culture, from The Beatles to Instagram...

A Hard Day’s Work

In The Beatles’ film A Hard Day’s Night, a television executive tries to persuade George Harrison to wear a shirt that he finds particularly heinous, apparently in some sort of product placement deal. Upon refusing, Harrison is told, “If you don't cooperate, you won't get to meet Susan… Only Susan Canby, our resident teenager.” Unimpressed with the woman described as “a trendsetter – it’s her profession,” Harrison, who refers to her as “that posh bird who gets everything wrong,” infuriates the TV exec by going on to say, “The lads frequently sit around the telly and watch her for a giggle. One time, we actually sat down and wrote these letters saying how gear she was and all that rubbish.” He’s then thrown out of the room for “knocking the program’s image”.

On the one hand, it’s simply a wry example of how the prerogative of the teenager – and what the whole ephemeral concept of cool rests on – is primarily about rejecting the mainstream, which is why it was so vitally important for Harrison to be seen to snub the TV exec’s attempts to tap the band’s cachet amongst youth to sell clothes; it reaffirms his image as a rock star. But it is also one of the very first depictions, and critiques, in culture of the now inescapably ubiquitous ‘fashion influencer’; a whistle-blowing attempt to reveal the ways in which highly regarded figures like The Beatles are used as a vehicle for manipulation in order to sell products.

Pre-internet Reflectivity

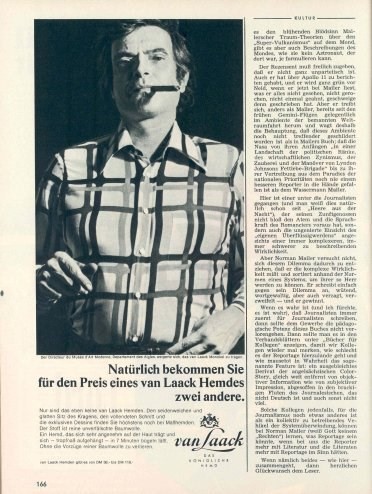

Back when advertising's jostle for your attention predominantly occured on the pages of printed magazines, Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers used the format to take aim at the bureaucratic art world. His work often looked retrospectively at his own body of work, as he acted as a collector/curator of his own previous pieces. He even positioned himself as the director of a mock American modern art museum. Ma Collection, first exhibited at The Cologne Art Fair in 1971, included a collage comprised of pages from the art fair’s catalogue amongst his own previous work, which included an ad page from German magazine Der Speigel, in which Broodthaers wears a van Laack luxury shirt and smokes a cigar. The caption said, “The Director of the Museum of Modern Art, Department of Eagles, refused to wear the van Laack monocle.” The artist wrote on the printed ad, “What should we think of the relations which link art, advertising and commerce? M.B. the director.”

In Marcel Broodthaers: Strategy and Dialogue, Deborah Schultz writes, “By displaying the advert alongside catalogue covers Broodthaers seems to suggest that these relations are rather close, and that, whether in the form of catalogues or in the form of a van Laack shirt, art/the artist is presented through advertising.” Equally, in making himself the curator of his own body of work, Broodthears mimics the conspicuous curations of their own lives that Instagram users produce on their feeds, the messaging about the blurring of art and commerce becoming poignant when considering the sponsored posts and product placement of influencers woven into their digital collage alongside carefully curated snaps.

Insta Art

More recently, as marketers followed their targets to Instagram, so too have artists; last year, artist Amalia Ulman presented her work Excellences Perfections as a performance via the medium of the social platform. Confusing her existing followers and IRL friends, Ulman began to create a highly curated persona informed by the tired Instagram tropes of not only fashion and beauty bloggers, but their young and impressionable female fans. At first glimpse, the selfies bathed in white light, coffees artfully arranged, inspirational quotes, avocado on toast, shopping and spa trips could be from any of your basic, macaroon-eating, sexy selfie-snapping insta-girls. But subtle clues emerged, suggesting that her persona was something more complex: jarring images of a medical drip, bandaged, post-augmentation breasts, and alarming captions alluding to personal troubles. However, her internet intimacy also worked as the perfect aping of the TMI of the digital age, and therefore even that felt plausible.

Gaining a new following from people seemingly genuinely into this content – as well as a backlash from people who knew her previously as an artist: “I used to take you seriously as an artist until I found out via Instagram that you have the mentality of a 15-year-old hood rat,” says one comment – Ulman’s posts mirrored the type of content we routinely see from fashion influencers, their perfectly-filtered and light-drenched life of coffees, hotels and free stuff, punctuated by insincere ‘thank-yous’ to brands. Of course, these are included too in Excellences Perfections; an underwear selfie is captioned with a thank you to genuine but not particularly popular Japanese lingerie brand Peach John.

The Parody Account

Alongside the emergence of artists like Amalia Ulman, Instagram has also seen the proliferation of the parody account – perhaps best observed by the success of Sociality Barbie. Sociality Barbie – often termed Hipster Barbie – not only deals in the white background and raw wood world of a Kinfolk utopia and the self-satisfied search for ‘authenticity’ and wellness, but realises a completed send-up by also including the requisite mention of labels that fit with her personal brand, lamenting the fact her ‘Sackcloth & Ashes blanket’ couldn’t fit in her suitcase. This kind of namedropping of brands doesn’t just reference the transactional advertising on Instagram, but also apes the self-satisfied tone of some of these posts, indicating that what the influencer gets from posting is not just cash, but the smug, knowing feeling that they are ranked important enough to be asked by brands to bring you this kind of messaging in the first place. #liveauthentic states Sociality Barbie. #getoutside.