Louche, liberated and sensationally incongruous – AnOther recounts the pivotal S/S71 Yves Saint Laurent show that caused public uproar

1971 was a dramatic year for Paris fashion. Even before the heightened scandal of Yves Saint Laurent’s Spring/Summer ’71 haute couture show, an air of nostalgia and generational disparity permeated the city’s streets and couture salons. In 1968, Cristóbal Balenciaga closed his Avenue George V maison because there was “no one left to dress”. Ready-to-wear had become the meat of most fashion houses and in just one year, from 1966 to 1967, the number of couture houses in Paris plummeted from 39 to 17. The reality for most couturiers was that their real estate was more valuable than their business.

The resignation of Charles de Gaulle in April 1969 was the dramatic finale to a presidential run that stretched back to the time of the occupation. The death of Gabrielle Chanel, one of Paris’ mythic fashion forces since the 1920s, in January 1971 seemed to mark a new era of cultural institutions and attitudes. When Luchino Visconti’s cinematic adaptation of Death in Venice, Thomas Mann’s haunting study of longing, old age, and the maddening insolence of beauty and youth, was released in the spring of ‘71, it had a strange resonance with the Paris set, where each age surveyed the other with curiosity. “The older generation were nostalgic for a youth they had lost, longing to feel the surge of desire and possibility of youth course through their own veins, while the younger generation yearned for a past they could not recall,” wrote Alice Drake in The Beautiful Fall. (2006)

“The older generation were nostalgic for a youth they had lost, longing to feel the surge of desire and possibility of youth course through their own veins, while the younger generation yearned for a past they could not recall” – Alice Drake, The Beautiful Fall

Nowhere was this more pertinent than when Marie-Hélène de Rothschild threw one of Paris’ last great bals costumés, in December 1971, which nodded to the gilded last quarter of the 19th century in the vein of the early 20th century’s flair for celebration. Cecil Beaton was the official photographer, capturing the ancestors of Proust’s faubourg meeting a new generation of social stars: Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, Jane Birkin and Serge Gainsbourg, Andy Warhol and Jane Holzer. The candidate to dream up Rothschild’s gown for that night was obvious: Yves Saint Laurent, Paris society’s darling designer who delicately treaded the balance between old world and new; sexuality and morality; politics and scandal.

The Show

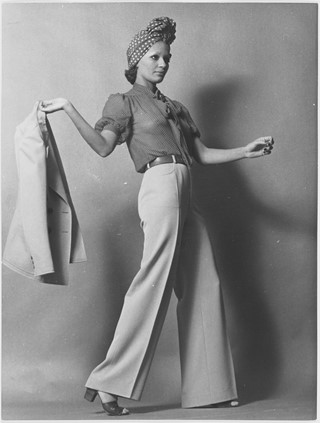

In the few months running up to the show, Saint Laurent’s studio at Rue Spontini had come to life with the addition of two stylish women that would breathe life into his vision: Paloma Picasso and Loulou de la Falaise. After meeting at a dinner party that October, Paloma Picasso began making jewellery, belts and shoes for Saint Laurent, drawing on her own sense of style which was achieved by shopping at flea markets and borrowing her mother’s 1940s dresses. Picasso wore velvet turbans and strapped wedges in the style of Carmen Miranda. Loulou de la Falaise came into the studio every day, collaborating on every aspect of the house with the 34-year-old Saint Laurent, offering exotic flair and an eye for colour and accessories.

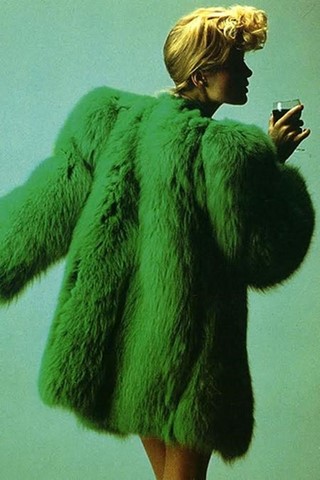

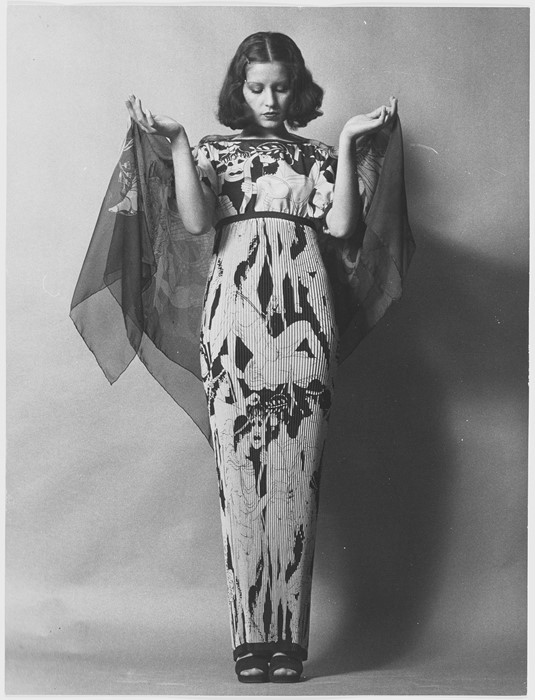

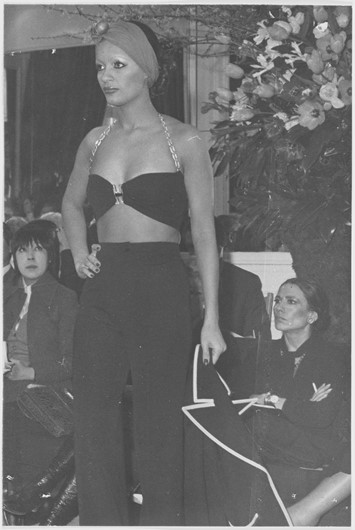

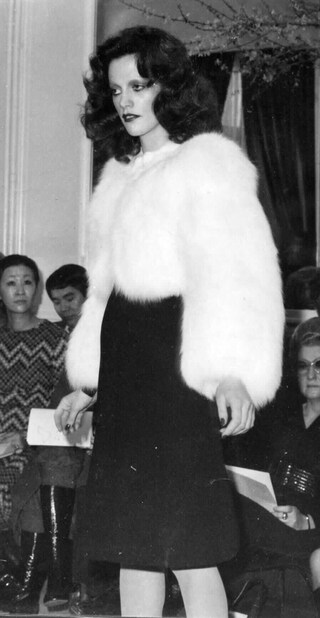

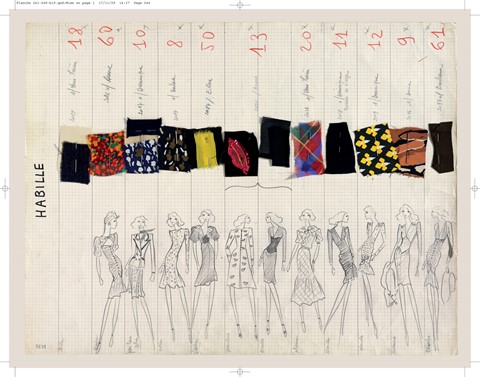

Saint Laurent was inspired by Robert Bresson’s 1945 film Les Dames due Bois de Boulogne, which tells the story of a society lady, in costumes by Schiaparelli and Grès, plotting revenge on her ex-husband by tricking him into marrying a former prostitute. The look of the 1940s pulsated throughout Saint Laurent’s collection, which featured plunging-neckline chiffon dresses worn with short, fur chubbies in electric green and blue. There were navy sleeveless blazers outlined in white piping with white lapels, a velvet coat that was covered in sequinned lipstick kisses smoking cigarettes, squarer and more pronounced shoulders, which would become the “Saint Laurent shoulder” from then on, clinging ruched waists that flattened the stomach, dresses printed with “pornographic” Greek ceramics, and wedge shoes and clumpy heels, following two generations of pumps.

“That was a reaction against the turn fashion had taken … the gypsies, all those long skirts and bangles … so I did my collection as a kind of humorous protest, only everyone took it seriously” – Yves Saint Laurent

A marked absence of underwear, dark lipstick-stained mouths and smoky eyes exaggerated the louche look. Loulou de Falaise bought the make-up for the models in London, as it was nowhere to be found in Paris. “It was the collection that everyone calls ‘kitsch’ (I hate that word),” wrote Saint Laurent in 1972. “That was a reaction against the turn fashion had taken … the gypsies, all those long skirts and bangles … so I did my collection as a kind of humorous protest, only everyone took it seriously.”

The Crowd

“He knew it was going to be a disaster,” recalled Loulou de la Falaise. In anticipation for the heated response, Saint Laurent’s tactically seated his allies amongst the most important guests. Loulou de la Falaise, dressed in a salmon-pink satin jacket and purple shorts, was seated with the French press and buyers, while Marisa Berenson, in a shrunken sweater, shorts and lace-up boots, took care of the Americans and Paloma Picasso, who had on a bright red turban and her mother’s black 1940s dress, was seated amongst the most prominent socialites. For the audience, their style was a hint of what was to come.

The collection wasn’t the first time 40s dresses were seen on a 70s catwalk – Ossie Clarke had been making yoked, bib-fronted dresses and tough-shouldered Blitz suiting for at least three years before that in London, where the flea markets were stripped bare of any fabric or accessory remotely 1940s. What made a difference was that most of the audience were of a generation that had lived through WWII and experienced Paris under Nazi occupation. Some argue that it wasn’t the 1940s references that outraged, but rather the blatant sexuality of the clothes, which evoked the memory of France’s ‘horizontal collaborators’: the women that slept with Nazis and were subsequently publicly shamed by having their heads shaved and paraded down the streets in their underwear.

“She was very sexy. People were used to couture models who were very spiky; it was a shock to see a big sexual girl like that” – Loulou de la Falaise

One of the models, a redhead called Annie Ferrari, was especially provocative in her braless and blowsy appearance. Guests cited her movements as sluggish, languorous and lewd. “Everything jiggled,” according to de la Falaise. “She was very sexy. People were used to couture models who were very spiky; it was a shock to see a big sexual girl like that.”

The Impact

The reaction to the collection was a harsh wave of negativity. Eugenia Sheppard of New York Post dubbed it “completely hideous, the ugliest collection in Paris,” while The Daily Telegraph labelled it “nauseating”. The reaction was so strong that there were even articles showcasing the press’ collective response. Some critics accused Saint Laurent of being influenced by ready-to-wear, while buyers were furious that short skirts were back when they had been pushing long. The press, according to Olivier Saillard, curator of 1971: La Collection du Scandal, considered Saint Laurent the heir to the great tradition of French haute couture. That’s why they couldn’t forgive him for the reminder of years of deprivation and restriction through which most of them had lived.

“I don’t care if my pleated or draped dresses evoke the 1940s for cultivated fashion people. What’s important is that young girls who have never known this fashion want to wear them.” – Yves Saint Laurent

It was the first time that the word ‘kitsch’ had been used to describe fashion, referring to a camp vulgarity that could only be appreciated with a sense of irony. What Saint Laurent was doing, however, was bringing the way that the women around him dressed into the court of haute couture. Flea market finds, second-hand clothes and Carmen Miranda-style styling were for a younger generation of women who had the excuse of not living through the occupation to be nostalgic for it. It’s this approach that made Saint Laurent the paradigm of postmodernity, collecting from a collage of references and moving glacially through symbols, era, styles and cultures throughout his career.

In an interview at the time, Saint Laurent said: “I don’t care if my pleated or draped dresses evoke the 1940s for cultivated fashion people. What’s important is that young girls who have never known this fashion want to wear them.”