From the New York punks to the Harajuku girls of Tokyo, we explore the style tribes who made their clothes their own

Beyond the catwalk lies the street – “It’s all here,” said original street style photographer Bill Cunningham – and beyond the exhibitionist fashion blogger thirsty for a photo op, the pavement holds the key to those individual sleights of hand which make clothing unique to the person wearing it. Whether the clothes have simply been shaped by the life of their wearer, or whether they were altered to suit, the narratives which accompany vernacular fashion are often much richer and more compelling than those that accompany virgin ready-to-wear.

If designer fashion is a slick boutique hotel suite – all contemporary art installations, orderly minibar and a maid that ensures no clutter – then vernacular clothing is a private bedroom full of favourite books and drawers of old birthday cards: the souvenirs of a life. Here, AnOther explores some of the ways people have impressed themselves on the clothes they wear, and, likewise, allowed their lives to shape their garments.

Embellished by Life

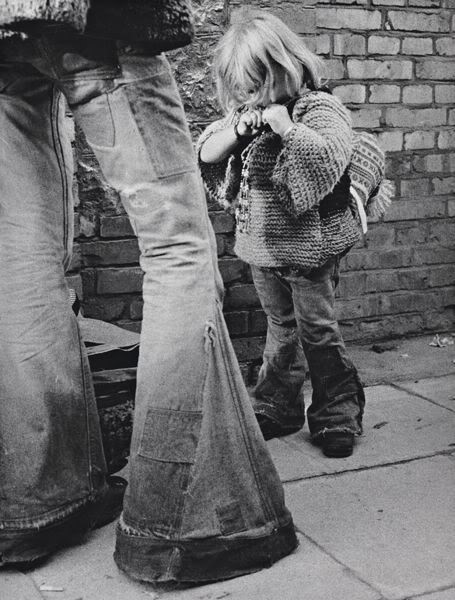

Denim and leather provide the perfect blank canvases for highly personal embellishments: the back-panel of a jacket or the pocket of a pair of jeans becoming a billboard through which the wearer can pledge allegiance to gangs, ideologies or favourite bands with hand-embroidered motifs. In addition to selecting items of note from designer collections, New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology archives significant items from other areas of fashion history. Its current exhibition, Denim: Fashion's Frontier, includes a pair of customised Levis in blue denim, embroidery, leather, appliqué, and beads from around 1969. The caption to the trousers reads: “These worn, torn, patched, and embroidered jeans highlight techniques employed by the 1960s counterculture movement that shifted denim’s cultural identity. 'Hippies' would often wear pre-owned clothes, which they would patch and embroider by hand. The personalized garments functioned as political statements against the material-driven consumer culture of post-war America.”

Soon after the hippy movement, homespun touches like embroidered personal statements or rips and tears that inferred 'real living' began to be applied to mass-market clothes in the factory. Ironically, the capitalist system that love-worn denim and embroidered motifs had originally offered an antidote to eventually found a way to monopolise on those unique currencies. It aped the naivety of hand-embroidered designs with machines, creating false stories of lives that were never lived in them, hammering rips and distressed patches into pieces to be hung new on racks.

DIY and Destroy

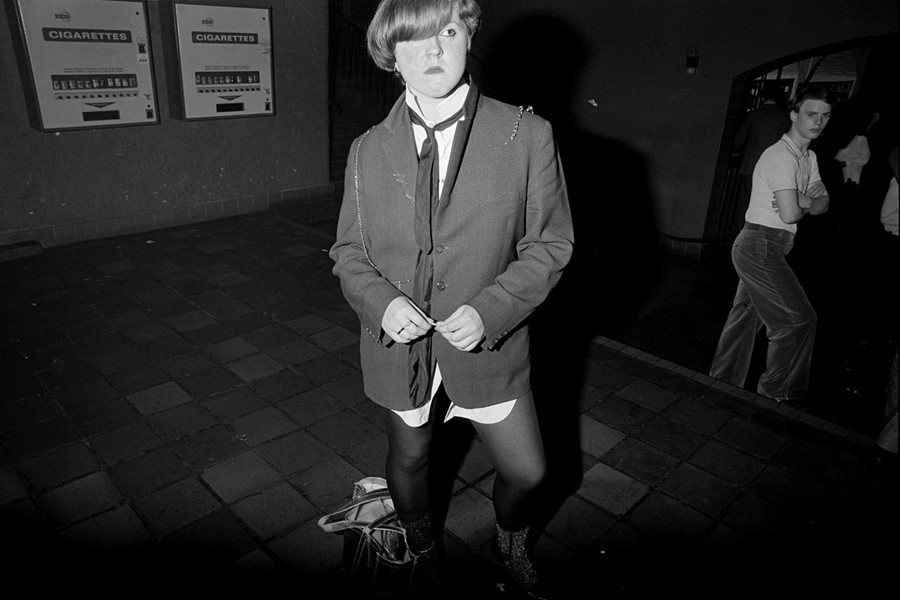

Although the US and British punks emerged almost simultaneously in the 1970s, their contrarian attitudes manifested in their clothing in distinctly different ways. The British take was intentional and considered, the American counterpart nihilistically battered. While aesthetically similar in some respects – rips in clothing and DIY embellishments like studs featured in abundance –there were fundamental differences underpinning the philosophies that brought them there.

British punk emerged from the bleak political backdrop of the three-day working week, and for all its anarchic tendencies, the movement had an escapist glamour to it. As Karen Knorr and Olivier Richon explained in their book Punks: "Chaos is constructed and signified; it is not a state of raw nature but a sign of counter culture." The clothes were artfully cut up, then closed again with studs and safety pins. Details like makeup and slogans scrawled on the backs of blazers were radical, but highly considered.

Across the Atlantic, American punk arrived as an antidote to hippy style: though it still railed against mainstream capitalist culture, it did so by opting out of the fashion circus. T-shirts were stained and shredded, too, but they got that way through relentless wear, and body-to-body contact at shows. The American and British varieties were visually similar, but one was shaped to fit the life of the wearer, while the other achieved its aesthetic through living itself.

A Rarefied Aesthetic

Some fashion tribes' desired looks are so far from anything that can be purchased off the rack that they must create their own pieces. From the 1970s onwards, the Harajuku area of Shibuya, Toyko, became home to an emerging fashion scene, and from 1978, Takenokozoku girls began occupying the pedestrianized area, boomboxes in tow.

Where traditionally, young Japanese girls learned to sew to make their own kimonos, these women made outfits from swathes of bright pink – different groups identified by colours and embroidered logos – and piled accessories upon themselves, before performing choreographed routines in the street. Subsequent style tribes in the pedestrianised area of Harajuku included American inspired rock'n'roll looks, and eventually the Harajuku girls (and boys) took inspiration from the worlds of Japanese cinema, comics and animations, putting together outfits to replicate pastel-hued Lolitas and kick-ass superheroes, each identity realised with a cartoonish flair.

Eventually retailers caught on and began selling these styles off the rack, but the objective amongst wearers was always authenticity. This determined creation of individuality is a philosophy that has underpinned Japanese-born streetwear ever since: iconic Japanese street label A Bathing Ape, for example, was founded in Harajuku in 1993, and built a cult following around highly limited runs of special edition collections. It’s a model that prevails to this day, manifested in the lines of dedicated consumers outside Supreme or Nike stores on the day of a limited drop. The clothes might no longer be DIY, but the thirst for rarity that developed on Harajuku’s streets remains.