AnOther explores how the feminist punk movement intellectualised – and even weaponised – fashion

“Revolution Girl Style Now”, proclaimed Bikini Kill – the all-female punk rock band who formed a seminal part of the early 90s Riot Grrrl movement. A group of female musicians fuelled by anger at the misogyny in national news stories and, at a local level, within the music scene itself, Riot Grrrl sought to frame feminist issues through a punk rock lens, sparking a third wave of feminism. Riot Grrrls railed against commercial, capitalist culture, mainstream standards of beauty, and expected female behaviour – and their relationship with clothing and self-image is one that disassociated political passivity from engagement with style.

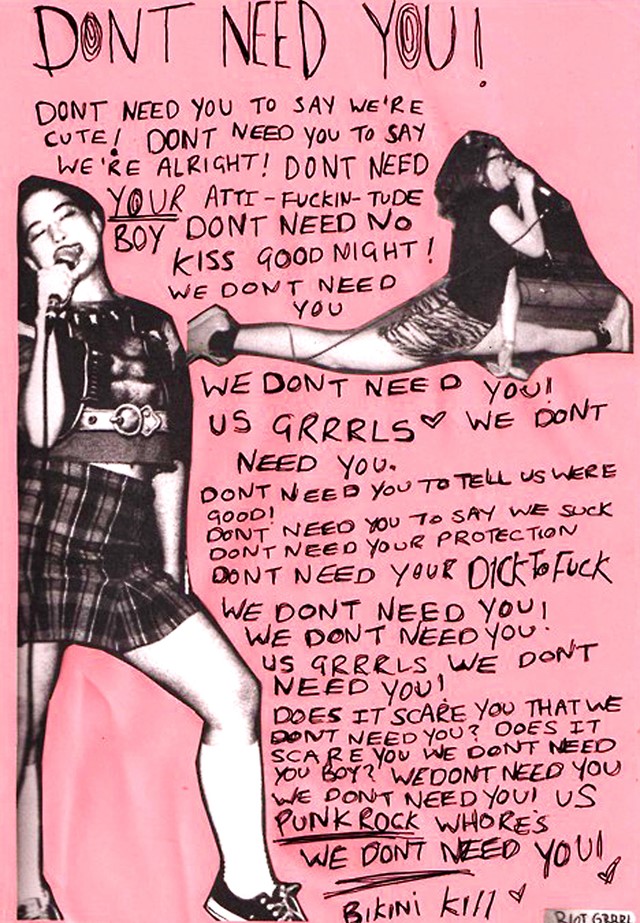

It would be reductive to talk about Riot Grrrl’s relationship to fashion in terms of a look: “Stop always worrying about what you look like and what clothes you wear, 'cause in the end it's not important. What's important is friendship and being creative,” said Kathleen Hanna, poster-girl for the movement and frontwoman of Bikini Kill and Le Tigre. However, in their DIY zines (which were how the girls connected, photocopying and mailing the low-fi publications cross country and handing them out at shows), many Riot Grrrls talked about their feelings towards clothes. They discussed them in first person narrative, and exposed comments people had made about what they should and shouldn’t wear to be respected, fit in, or feel safe. Here AnOther explores how Riot Grrrls intellectualised – and even weaponised – fashion in their work.

True statement fashion

At the opening of biographical documentary film The Punk Singer, Kathleen Hanna explains how she told novelist and punk poet Kathy Acker that she wanted to write because “nobody has ever listened to me my whole life and I have all this stuff that I want to say,” to which Acker replied, “Well, you should be in a band because nobody goes to spoken word but people go to see bands.” So, off she went and started a band, using the platform to direct her thoughts to an imagined patriarchal male. (Hanna would describe her later work in Le Tigre as “talking to the girls”).

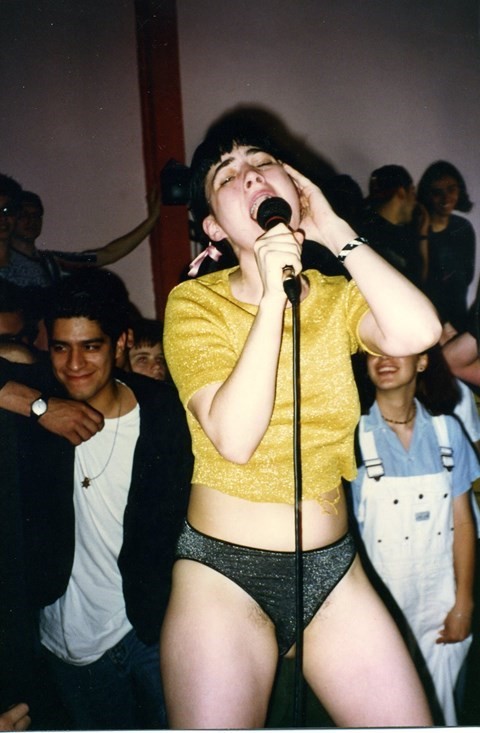

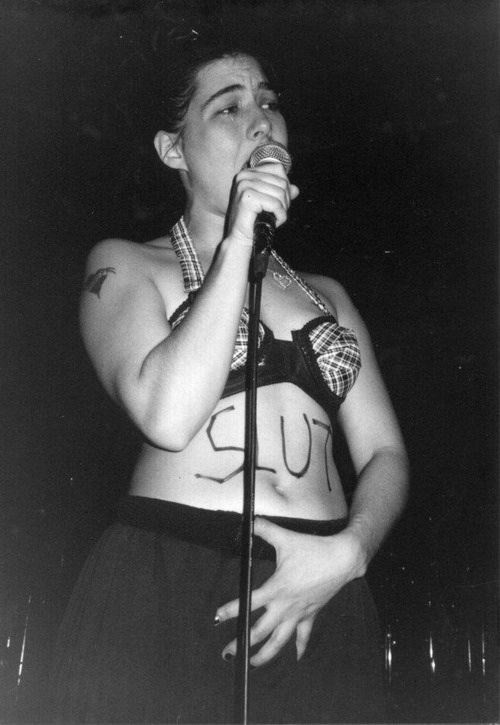

“I believe in the radical possibilities of pleasure, babe,” asserts Hanna in Bikini Kill track “I Love Fucking,” a song that muses on the gender politics and rape culture, exposing the internal conflicts between instinctive desire and an intellectual understanding of patriarchal society. If performing in a band was the best platform to shout these messages, then Hanna tapped fashion for amplification. On stage, she would often wear nothing but a bra top, with ‘Slut’ written on her torso, but this statement-making harks well back to her time as an 18-year old student, when she put together a fashion show featuring garments printed with photography and slogans. In The Punk Singer, Hanna describes an incident that happened when she was a student at Evergreen State College in 1989, where she was studying photography. Hanna’s housemate was assaulted by a man at home while Hanna was out working on silkscreens for a photography project. Hanna, vowing to “make sure this never happened again,” channelled her rage into the project she was working on. “I couldn’t keep it out,” she says. “I made a dress that said ‘As he drug her upstairs by her neck.'” The dress was the hero piece in a collection Hanna showcased at a fashion show she organised in the university’s library.

Exploring privilege and gender

For the Riot Grrrls, an interest in their looks came from a place of understanding the privilege, power, opportunities and obstacles that the way you look can present. Many Riot Grrrl zines dealt with the nuances of feminism from a minority race, class or gender perspective, and in her tongue-in cheek zine My Life With Evan Dando Hanna acknowledged her own privilege: “Because I am closer to the thin, white, small nosed idea that advertising racists shove down our throats, I am more of a star than the big girl at the party,” she wrote.

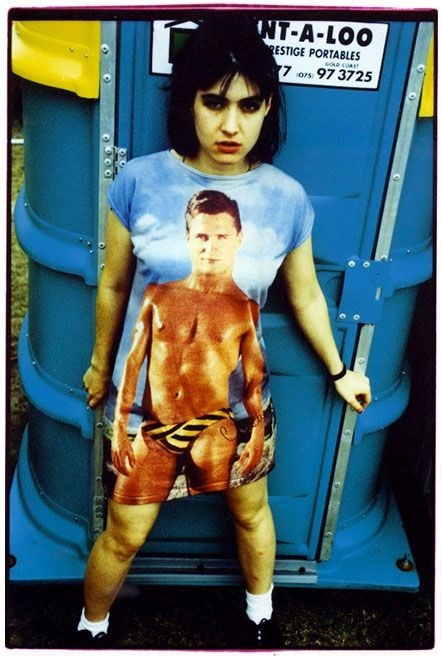

With a heightened consciousness of their self-image came an understanding of how aesthetics could be harnessed to deliver the message of ‘Revolution Girl Style Now’. Image became a tool that Riot Grrls could employ to explore their own ideas, and equally to provoke a reaction from others. In a 2013 interview with Elle, Kathleen Hanna explained one costume in particular, one that mirrored the screen-printed image style of her college photography fashion show collection – a T-shirt dress featuring a photograph of a Speedo-clad, oiled-up man. “Some of the costumes had specific meanings," she said. "I had this man dress. It was actually a nightie, and it had a Chippendale's dancer on the front and the back. He was like the man inside of me. I was sort of playing with the idea of gender. No one's female and male, we all have so many different traits. It's just a lie that these certain traits are male and these certain traits are female. So it was like, this is my dude. This is the dude in me.”

Reclaiming girlishness

More a reclamation than a subversion, girlishness and stereotypically ‘girly’ tropes featured heavily in the Riot Grrrl aesthetic. Cute hearts would dot the Is on self-penned zines and T-shirts, and pink was a popular – sequins, too. Out-right opposed to the capitalist merry-go-round that they felt the fashion industry perpetuates, and frequently calling out glossy magazines for encouraging eating disorders, the personal confessionals in the Riot Grrrl self-published zines offered a refreshingly contrary take on the trends of the day. In an issue of Cupsize – a zine from two New York riot grrrls Sasha Cagan and Tara Emelye – Sasha Cagan objects to the way a fashion feature in The Village Voice flippantly attributed the sudden abundance of ‘girlish’ clothes in stores as part of a trend towards liberating return to early adolescence, “the period that precedes the command to shut up and simper. Cagon’s searing response came illustrated with a picture of the pair of authors as children with the caption, “Sasha and Emelye out on the town in their baby doll wear,” “We felt so liberated!”

As the Riot Grrrl movement began to grow dedicated followers, inevitability fashion brands began to tap into what they saw as something cool that women liked and might buy into. Cagon’s gripe was that “the politics get watered down somewhere between the Riot Grrrl signifying aesthetic and the SKU coding of the price tag” and that it was wrong of The Village Voice to dress this up as empowerment. “The beauty of that period cannot be invoked by carrying a lunchbox around with me… cotton candy outfits are not going to transform my spirit into a nostalgic girl emancipation,” Cagon wrote. “They are being created for us, from the hierarchy above, to fatten corporate dividends. It’s pretty simple really, I don’t think anyone really pretends to buy empowerment at the cash register.”