We revisit the post-waif hedonism of Tom Ford's Studio 54-inspired vision for Gucci

Today, when one thinks of Gucci, Alessandro Michele's signature eclecticism – ditsy florals, saccharine colours and girlish silhouettes – immediately spring to mind. This aesthetic is in total opposition to the house's output during the 90s, when it became synonymous with hedonistic glamour under the creative hand of Tom Ford. In fact, thanks to Ford's firm, high-octane directive, Gucci underwent a complete transformation and, following a slightly tumultuous period, by 1996 had been firmly restored to a position of utmost glory.

Once a go-to for the leather, luggage and furs of jet-setting celebrities, in the 1980s Gucci had become slightly stagnant within the US market (counterfeits were in abundance and Aldo Gucci’s decision to launch a line of cheaper product resulted in it becoming a little too ubiquitous in airport boutiques), and a bit too posh in Europe (in fact, Peter York and Ann Barr’s 1982 publication The Official Sloane Ranger Handbook described the upper-class penchant for a pair of horse-bit loafers purchased at the Old Bond Street shop as borne of respect for its “smart but military equine look, like a good piece of uniform with regimental brass”). Then, the luxury business of the early 90s was facing hardship, largely due to a widespread anti-fashion sensibility that infiltrated the mainstream. Its roots were a reaction to the conspicuous consumption and widened wealth disparity of the late 80s, with a poor economy bringing it all to a crashing, crowd-pleasing halt. What follows is the birth of Margiela-inspired deconstruction, the downbeat photography Bill Clinton termed "heroin chic" and the prepubescent-looking, angsty poster girl of it all: the waif.

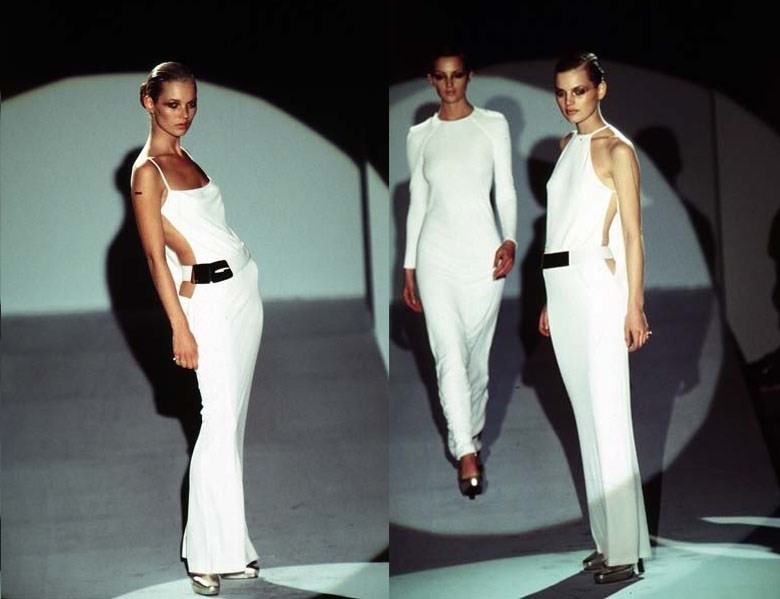

"It lit the fuse of the sex bomb" – Tim Blanks

“When I think back to the early 90s, when he first arrived on my radar screen, fashion was buried deep in the shapeless layers of the horrible grunge look", wrote Anna Wintour in 2004. “Along came Tom with his low-cut hipsters and his slinky jersey dresses, and grunge was sent scurrying off back to Seattle.” It was Tom Ford’s A/W96 collection in which, he said, “it all came together for the first time.” He introduced some of the key motifs of his ten-year reign at the Florentine company: a tailored, Helmut Newton-esque androgyny; dark-eyed, chignoned beauty; city-slick pinstripes; the red velvet tuxedo for him and her; super skinny belts and dramatically large furs; slinky white jersey gowns with peepholes fastened by smooth golden hardware. Tim Blanks pointed out that it “lit the fuse of the sex bomb” and that Ford’s vision combined points of American sportswear with the “notion of the power of sin,” while Wintour’s Vogue described it as “the fashion equivalent of a one-night stand at Studio 54”.

The Show

Without a doubt, the subtext of Tom Ford’s shows was, first and foremost, S-E-X. Having moved to New York just in time to experience the glitzy debauchery of Studio 54, Ford drew inspiration from nightlife for his Gucci fashion shows. The venue for A/W96 was dark, and the soundtrack sensual: Patti Jo’s Make Me Believe In You, The Fugees’ Killing Me Softly With His Song, Love Unlimited’s Under The Influence of Love and Dusty Springfield’s The Look of Love. Ford employed a spotlight on the runway, a move which Gianni Versace pioneered – but, while Versace’s shows were like pop-tastic parties, Ford’s was more of a grown-up soirée. “I wanted that girl to be in the spotlight,” said Ford. “I decided to kill the backlighting and put the clothes under a spotlight because I wanted to control the room. That sounds silly, but with a spotlight, you can’t see your friends across the aisle; you can’t wave at people and roll your eyes. You focus on the show.”

The People

A photograph of Tom Ford’s black lacquered desk at Gucci shows an Andy Warhol portrait of Roy Halston staring out, somewhat aloof. It was under this watchful gaze that Ford designed the A/W96 collection, drawing from the designer’s use of jersey and the long, columnar dresses he made for Elsa Peretti. Just looking at the louche trouser suits, dramatic fur coats draped over the shoulders of models and the huge lapels and necklaces, it’s clear that the days of his Studio 54 youth were Ford’s biggest reference point. “I think everyone’s notion of beauty is formed – your sense of taste, most of your values and opinions are formed in your childhood – the first thing that you ever see that makes you think, ‘God, that’s beautiful’: Those things stick in your mind forever. So I will probably forever be stuck in the sixties and seventies,” he has said.

On another note, perhaps the best appointments Ford made at Gucci was that of Mario Testino and Carine Roitfeld, who together created groundbreaking advertising imagery for the brand. For this particular collection, Testino shot South African model Georgiana Grenville in a Rem Koolhaas interior, provocatively gazing out to the viewer in a silk shirt unbuttoned to the navel and flirting with her lover in one of the streamlined jersey gowns, her slicked-back hair matching the gold-tone buckle under the peephole. The images perfectly resonated Ford’s clean, polished vision of sensual sexuality and luxury.

The Impact

When asked what he considered his legacy of Gucci, Ford answered: “I think I brought back hedonism, a certain kind of ostentatious fashion. I brought back a certain sexual glamour, which we probably hadn’t seen since the late seventies because of the way that AIDS altered fashion.” It was that approach that attracted swathes of actors and actresses to the brand, controversially exploding the idea that the brand was synonymous with sex and celebrity upon a generation of young consumers. Within a year of his debut, Gucci profits were up 90% and Ford eventually became more involved with Gucci Group management, designing for Yves Saint Laurent and steering the acquisitions of Alexander McQueen and Stella McCartney.

Ford felt that this particular collection proved Gucci’s clothes were more than mere editorial-friendly adjuncts to a lauded accessories business. “The strategy from the beginning was: Make the brand appealing through fashion and then sell loafers,” he told fashion critic, Bridget Foley. “Madonna went out in our hip-huggers and our loafer sales went up. Now, here were pinstriped suits that started to sell, that everyone from thirty to seventy could wear. I am a commercial designer and I am proud of that; I have never wanted to be anything else. This gave other people an inkling of what I always knew – that we could really sell clothes.”