From jazz bars and spoken word poetry to berets and black turtlenecks, we chart the evolution of beat from subversive to chic

“Any attempt to label an entire generation is unrewarding,” John Clellon Holmes wrote, in an essay entitled This is the Beat Generation for The New York Times in November 1952, “and yet the generation which went through the last war, or at least could get a drink easily once it was over, seems to possess a uniform, general quality which demands an adjective…” The uniform quality Holmes was addressing was one of weariness, and the word coined to refer to it, ‘beat’. “It implies the feeling of having been used, of being raw,” he continued. “It involves a sort of nakedness of mind, and, ultimately, of soul.”

The beat movement, though short-lived, existed in a blaze of glory through the 1950s, during which time some of the most revered figures of 21st century counterculture channelled their frustration with the materialism which flourished in the postwar years into novels, poetry, music and artwork. Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac and William Burroughs dominated the literary sphere, while fast, frantic jazz threatened the music establishment. Throughout creative culture, the powerful belief held by a select few that there the most exciting ideas were to be found beneath the establishment’s dark, gloomy underbelly carried it along for the best part of a decade. And yet, when beat had burnt itself out, and the ideas underpinning it disseminated out into more general anti-capitalism ideas around the hippie movement of the 1960s, what remained were the beatniks.

The Emergence of Beatnik Culture

Beatniks – so-called by writer Herb Caen partly for their having evolved out of the beat movement, and partly because "Russia’s Sputnik was aloft at the time" – adopted the fashion which had emerged out of beat ideology and developed it into an aesthetic all of its own. In the 1950s, the term became the media’s moniker of choice for a member of Bohemian counterculture – anybody, in fact, who rejected the mainstream in favour of artistic self-expression – and was bandied around accordingly. It wasn’t popular among the movement’s originators, however; Caen once recalled running into Jack Kerouac at nightclub El Matador, and being formally asked to rescind it. “You’re putting us down and making us sound like jerks,” Kerouac was reported to have said. “I hate it. Stop using it.” Nonetheless, the term survived, and was used to refer to those countercultural rebels who existed before the hippie movement came into its own.

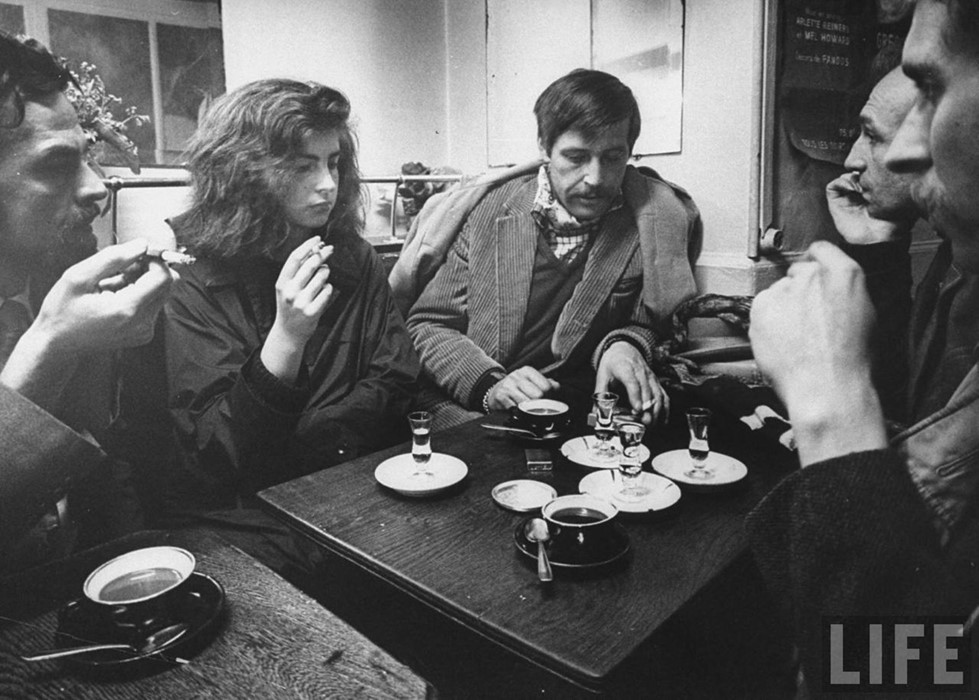

The word's stylistic connotations, however, have come to represent a whole decade of the intellectual underground. Most important of all the movement's tenets was the attitude required to pull off such a look – an intense nonchalance, a self-contradicting distaste for worrying about how one looks, and an all-consuming intellectualism which could drive one at a moment’s notice into weeks of self-induced despair – scribbling in poetry in notebooks, a Gitane hanging absentmindedly from the mouth, and so on.

Anti-Fashion

Their literature was dismissed as pure provocation, a means of getting attention rather than of expressing onesself, but where the beatniks' intellectual output was exhibitionist, the sartorial was anything but. The post-war boom which flowed over the USA in the late 1950s brought with it more than simply a greater quality of life. With money came materialism – a plague that members of the Beat movement was determined to withstand. Paradoxically, their determination to abstain from bettering themselves aesthetically, choosing to focus instead on intellectual improvement, resulted in a recognisable style all of its own.

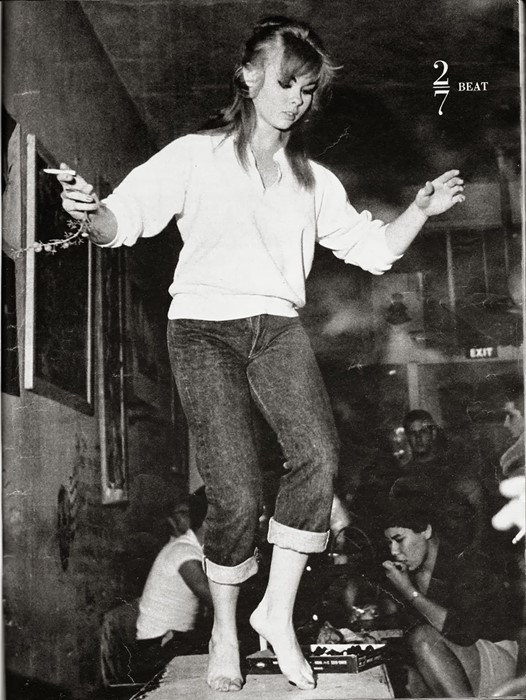

While in the mainstream, adolescents were donning billowing hourglass skirts in an echo of Christian Dior’s New Look, beatniks opted for black, lots of black, and favoured streamlined silhouettes which deferred attention away from themselves. Straight-leg cigarette pants and black turtleneck sweaters became a uniform of choice, while women took to wearing black leotards and stirrup slacks – tight clothes which allowed freedom of movement and spoke volumes about their sexual freedom. Be-bop trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie became one of many inspirations: his goatee, beret and horn-rimmed glasses were endlessly emulated by legions of followers and pseudo-intellectuals.

Hair was a hot topic in the 1960s: determined to rebel against beauty salon culture and the trend for heavy make-up and perms which proliferated with the mainstream, beatnik women wore their hair long, straight and loose. Men, similarly, demonstrated their cultural identity by allowing their hair to grow – a highly political action which carried connotations of having resisted signing up to fight in the war. In 1967, actors James Rado and Gerome Ragni distilled the cultural insecurity which surrounded long, flowing locks into a whole Broadway music, aptly entitled Hair. The production was a vibrant, joyous expression of anti-Vietnam feeling – in the live shows cast even invited the audience to come up on stage and to join them in a ‘be-in’ – and all this at a time when students were frequently expelled from school for letting their hair grow.

Most important of all, however, was the attitude required to pull off such a look – an intense nonchalance, a complete distaste for worrying about how one looks, and an all-consuming intellectualism which could drive one at a moment’s notice into weeks of self-induced despair – scribbling in poetry in notebooks, a Gitane hanging absentmindedly from the mouth, and so on. "It is not my fault that certain so-called bohemian elements have found in my writings something to hang their peculiar beatnik theories on,” Kerouac once wrote, determined to shake off the term, and yet having no luck with it. He remained the poster boy for the movement for generations to follow.

Representation

Original imagery of beatniks in the 1950s and 60s is scarce, but as a subculture it has been parodied endlessly in films and literature – at first by the contemporary conservative American press, who were horrified by the sexual freedom and drug use they associated (not without reason) with the movement, and later by sentimentalists eager to elevate it.

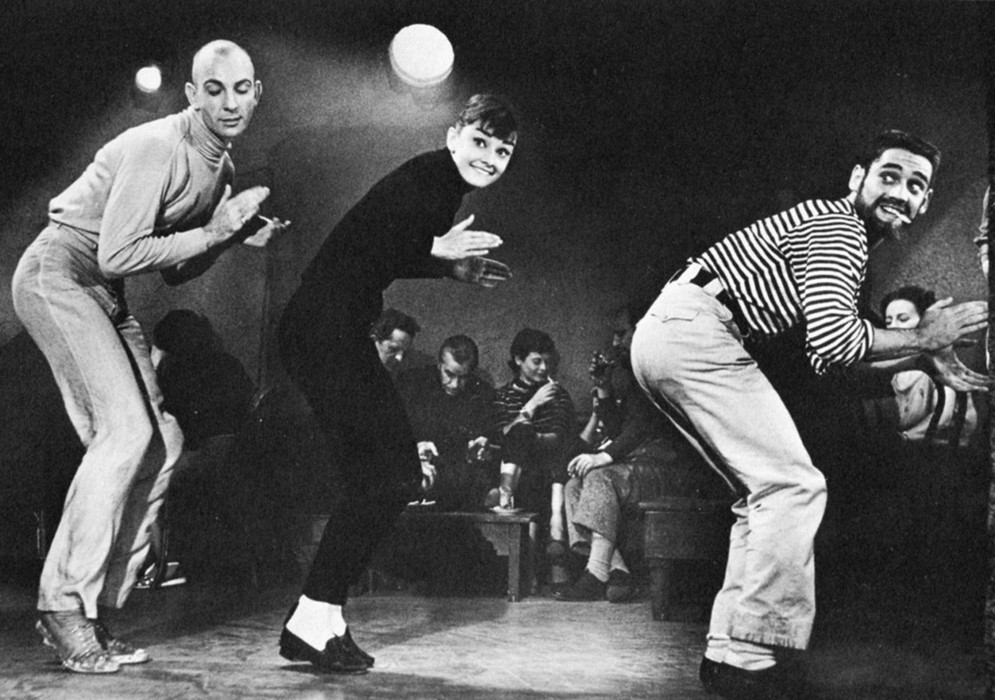

The 1957 film Funny Face, directed by Stanley Donen and starring Audrey Hepburn, presents beatnik culture in its most recognisable form: distilling it into coffee shop conversations, bearded men in berets, and impromptu bongo drum performances. "We're using this shop as a background for some fashion pictures for Quality Magazine," Fred Astaire as Dick Avery tells Audrey Hepburn's character Jo Stockton in the film. "I'm sorry, but I can't let you do this," she replies defiantly. "Dr. Post would never approve. She doesn't approve of fashion magazines. It's chichi and an unrealistic approach to self-impressions as well as economics."