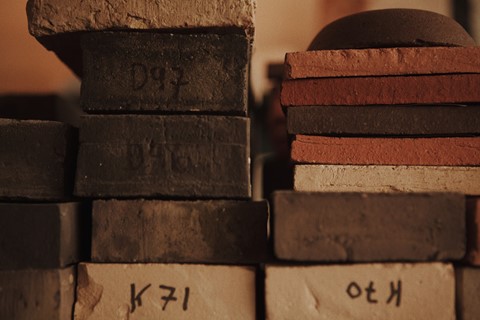

The world according to Faye and Erica Toogood is a blissful thing, a place where every detail is considered and questioned to ensure it matches their own version of perfection. The sisters’ empire is currently limited to a high-up floor in an unassuming office building on Old Street but it’s a tantalising amuse bouche of what a Toogood life might encompass; decoration is sparse but the essential items are carefully chosen, on a long table sits a set of cream bowls glazed with abstract strokes of indigo. There is a high-backed grey sofa, and the requisite row of gleaming Macs lined up along otherwise bare desks. It’s not exactly minimal though; tucked away behind one corner is a “library” of materials comprising dozens of small samples of woods and metals with varying grains and finishes. And around another corner is Erica’s domain, where she cuts and tailors the pieces for the collections which the pair create together.

Until now, the sisters have been showing their radical clothing concept in Paris. But on the day that you read this, they make their London fashion week debut with the presentation of their fifth collection (called 005) on the rooftop of a school in Soho. “We’re in a bubble,” observes Faye “we weren’t sure if the fashion industry had really acknowledged what we’ve been doing.” And what is it they do? “We question everything,” says Erica “not to purposefully reject the way it’s done, but to find our own methodology.” It’s a fitting moment for them to step on the London Fashion Week schedule, given the current state of flux which the industry finds itself in.

You will know Faye for her design work. Her studio houses creatives of all disciplines, from furniture to sculpture and architecture, working across all manner of design endeavours. It was as part of a project with Covent Garden, called 7 x 7, that she worked closely with younger sister Erica, an established “scissorhands” pattern cutter and tailor who had worked in theatre, to create 49 coats which hung above a cobbled street to celebrate and remember the trades which had been lost in the area. Their first collection was an inspiring offering of eight coats with names such as The Beekeeper, The Milkman, The Oilrigger and The Roadsweeper, each one a considered tribute to its namesake trade.

A sense of sustainability and gentle progress is integral to Toogood, so those first coats are still present in 005, but they are joined by skirts, shirts, dresses and trousers too. The collection is based on the fruits of a “mudlark”. Erica has a friend who is a mudlarker, meaning he has a licence to collect and bring away found objects from the bed of the River Thames. He went on a “mudlark” and sent the results to the sisters in a small box. The objects are a fascinating variety of trinkets which include Elizabethan pins, buttons, musket balls, clay pipes, shards of tiles and shells with tiny holes.

“We’re great collectors and like to look both back and forward” says Faye, re-examining the contents of the box which sits open in front of her. “You’ll find something from the 16th century and underneath it, a penny from yesterday. We were also interested in the idea of stream and current, is it about going with the tide or against it? I think our instinct is to go against.” The mudlarked objects appear re-formed in jesmonite and will be sold as accessories, while the clothes themselves are practical “vessels for collecting”. Every piece has at least one grommet which you could tie a discovery to, while there are more extreme versions which are covered in rings making the garment something which can be continually reinvented by swapping the objects attached to it. The fabrics, too, are a nod to the river; The Warden coat and The Boxer Long are formed in a glimmering industrial material intended for oil filtration while The Apprentice jackets comes in tufts of rigorously tactile rope.

When the Toogood sisters began their label, the idea of unisex clothing was one of their defining tenets. The fashion industry has certainly begun to catch up with their approach in the two and a half years since then. They make all their garments on a sizing scale from 0-6, whereby 0-3 is cut on a woman and 4-6 is cut on a man, “but that’s not to say you can’t move between” points out Erica, “women who like oversized will often veer into the men’s numbers while a Japanese guy often looks great in a 1.” And while they are ostensibly presenting 005 at a women’s fashion week, there will be models of both genders and they’re open to the idea of showing at men’s too.

“I’m a kid of the 80s” says Faye, “back then, unisex actually meant an androgynous look – women in men’s suits, really. But now I think we can derive our own identity.” “Exactly, men and women, young and old are evolving our clothes in different ways” says Erica, “a 20-year-old guy in Nikes and a 70-year-old woman with grey hair may wear the same coat, but it evokes something entirely different in each – besides, we’ve sold organza dresses to men who look incredible in them.” The sisters themselves are excellent examples of a non-gendered, individual mode of dressing; Faye is in head-to-toe cream with oxblood nails and a sprinkling of opulent jewellery while Erica is all in black with a wonderful mass of short, curly hair.

There’s a five-year age gap between the sisters which meant they “didn’t understand each other” growing up. Until Faye was 12, they lived in rural Rutland with their quite “alternative” parents. “There was no television and no gender-specific toys,” Faye remembers. “Mum would drive miles to get to the nearest health food store, and she’d be shovelling oats, sesame seeds and sunflower seeds into brown parcels,” recalls Erica. “Yes and all we really wanted was a white ham sandwich and a wagon wheel!” laughs Faye.

But the sisters trace the origins of the 005 collection back to their close-to-nature childhood. Their mother was a florist and their father a “keen birdwatcher” so the great outdoors and their local farms were their natural environment. “I think that’s where Faye’s questioning mind originated. She’d squirrel things into the house and put them in boxes. It’s reminiscent of the archive here,” muses Erica. Faye agrees that “this collection has that autobiographical element albeit in an urban environment. It’s all about looking down and finding something shiny in the mud.”