In the first edition of a two-part Galliano special, we remember the show in which Kate Moss and Carla Bruni were transformed into Russian princesses and dramatics reigned supreme

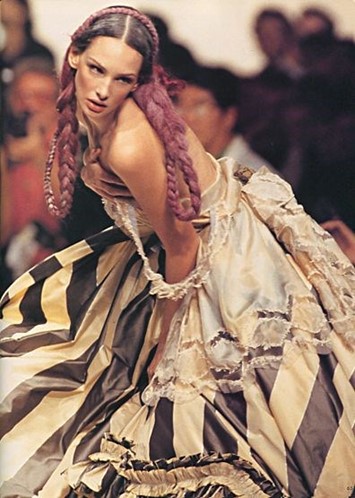

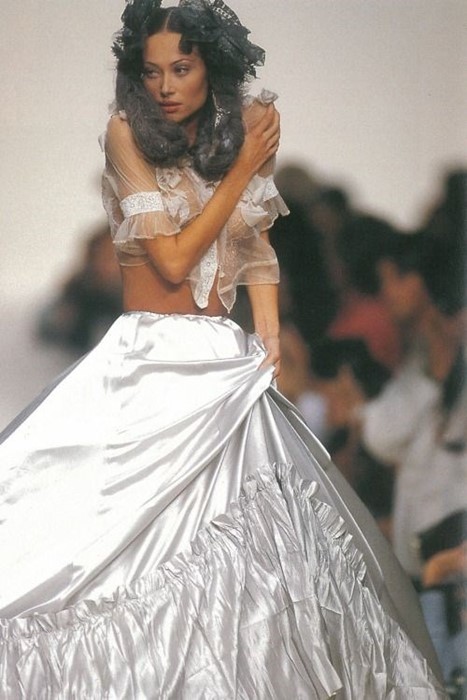

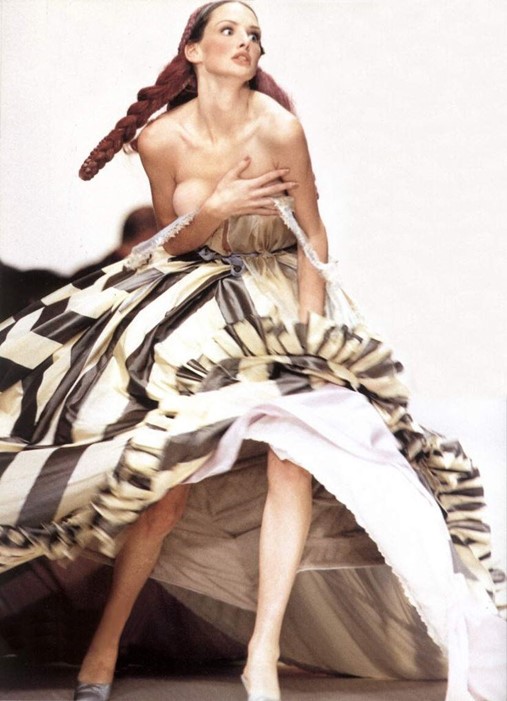

Once upon time, there was a princess called Lucretia. The daughter of elegantly debauched parents, her glamorous, sometimes-cruel upbringing was worthy of Tolstoy’s imagination. Much like the most fashionable of 1860s Russian nobles, Lucretia spoke and dressed à la Francaise, courtesy of her parents’ expensive taste. However, much to the Prince and Countess’s dismay, the young princess also inherited their independent streak, falling desperately in love with one of the estate’s many serfs and plotting an escape from the claustrophobic theatrics of St Petersburg society. One snowy evening, she departs, sprinting through the forest in her hooped cage crinoline, her diamonds hidden in her bustier and only her ermine muffs to keep her warm. Howling wolves are chasing her and the yards of silk and taffeta that trail behind her are no match for the prickly terrain, nevertheless she reaches her lover’s humble abode in one piece, with only a moment to spare before she kisses him goodbye and borrows his piped pyjamas and boyish tailoring to create a disguise.

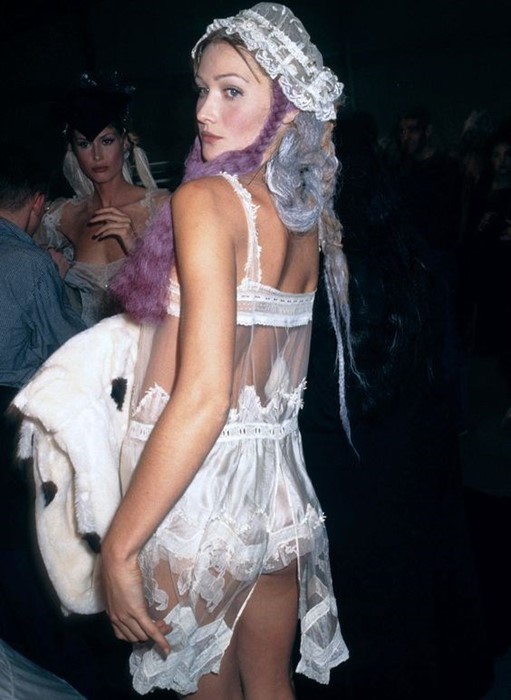

Aboard a third-class carriage, dressed as a waifish young man, Lucretia goes as far as the railways will take her, allowing herself to drift through the continent and rely on the generosity of her travel companions. She chances upon the dotty Duke and Duchess, eccentric polka-dot covered Brits who immediately take an affectionate liking to her. They welcome her to stay with them in the Scottish Highlands, the furthest she can be from the chattering eyes and ears of her hometown – and the height of gothic Victorian sophistication. Prince Lucretia is introduced to British society at country manors and races, where she picks up the habits of smoking, gambling, drinking gin, and wearing flirtatiously short fur-lined kilts, tartan knickers and dramatic tulle-stuffed bell sleeves. It’s not long, though, before she meets her dashing young Lord, falling in love once again and living happily ever after in her softly hued, slinky bias-cut silk dresses and jewel-embellished sashes.

What may sound like the end of the story was only the beginning of one for John Galliano. At 6:30 PM on the 8th of October 1993, in the tents at the Cour Carrée du Louvre, Galliano presented his Spring/Summer 1994 collection to the lucky few who had been sent a tea-stained, hand-written scroll of an invitation. After missing a season due to financial insecurity, Team Galliano returned to the spotlight with a fashion fairy-tale inspired in part by a Vanity Fair article on remains of the Romanovs and the lost Princess Anastasia, Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, Jane Campion’s The Piano, the Duke of Edinburgh, and Madeleine Vionnet’s 1920s bias cut. In true Galliano tradition, a narrative was firmly in place from the beginning to the middle to the end, with the models becoming actresses and the clothes acting as costumes, dramatically guiding the audience through a fantastical odyssey of romance and history. Even more effective was the unadorned white runway (a far cry from the theatrical sets that Galliano would later favour) which was nonetheless equally effective in framing a collection that suspended disbelief. In a sea of laissez-faire grunge and Margiela-esque deconstruction, Galliano returned to old-world skill and technique to create a moment of pulsatingly original, objective beauty and heartfelt sincerity, with all of the frills included.

The Show

“When a woman wears a hooped skirt, the gestures through her arms and torso become more expressive, and the grace of her gait is heightened by all that undulating, oscillating fabric,” says Janet Patterson, The Piano’s costume designer. Released earlier that year, the film’s influence infiltrated the attic studio that Galliano and his small team occupied in the factory of Plein Sud, a mass-market sportswear label that offered them a free space to work. Galliano’s crinolines, however, were utterly innovative renditions of their Victorian whalebone ancestors – his caged structures were built with hoops of thick fibre-optic telephone wires to allow over 16 yards of fabric utterly weightless structure and liberal movement. There was also the generous dose of transparency in the form of wispy chiffon tops, the unexpected bareness of which, Galliano believed, made the crinolines look modern. Each piece was finished with delicate detailing, such as faggoted tulle, appliqué feathers hand-cut from gelatine-coated chiffon, and ‘engineered lace’ made by sewing thread onto soluble paper. “It was all about these traditional and non-traditional dressmaker’s skills,” says Jennefer Osterhoudt, who was Galliano’s girl Friday for over seven years and now runs a Hackney-based archive, The Arc. “There was one top which we tea-stained by hand and traced a calligraphic love poem onto it while it was wet, so that it would bleed and fade.”

Amongst Galliano’s inspirations was an article in the January 1993 issue of Vanity Fair that explored the discovery of the Romanov bones; the absence of the young Grand Duchess Anastasia; and the DNA connecting them to Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh. Hence Lucretia’s ‘highland fling’, a section of the show dedicated to playful flirty dresses and micro-kilts and British eclecticism. “That was when it switched to 1994,” Galliano explained to MTV after the show. Jeremy Healy made a soundtrack that started with Sergei Prokofiev’s festive Lieutenant Kijé, chopped up with a recording of wolves howling, which models such as Kate Moss were instructed to look back to every time they heard it. For the highland fling, or ‘tartan murder’ as Healy calls it, The Piper’s Maggot, a traditional Irish jig, was layered Ditch disco and hints of glockenspiel, followed by Michael Nyman’s A Wild and Distant Shore from The Piano combined with the sound of tribal drummers in hot pursuit.

According to Osterhoudt, Galliano hadn’t even seen the Jane Campion’s film yet found it magnetic. “John needed glasses, so he didn’t like going to the cinema. I saw The Piano in the San Francisco, where I’m from, and I went and bought a vintage crinoline there,” explains Osterhoudt. “When I went back to Paris, I told him all about it and he would always be making me re-enact all of these movies and weird obscure American things he hadn’t seen, so I had to run around the studio in my crinoline, rolling on the floor and grabbing onto the beams, pretending that I was being raped! John loved it and would make me do it again and again – but he never actually saw the film.”

The People

Paramount to Galliano’s success was his team of close collaborators and supporters. There was Steven Robinson, who would remain John’s right hand until his death; Bill Gaytten, chief pattern-cutter; Amanda Harlech, the story-telling stylist; Mesh Chhibber, who worked on research and publicity; Jeremy Healy, the DJ behind each show’s soundtrack; and Suzanne Deacon and Jennefer Osterhoudt, first assistants to Steven and John. “Everyone worked on everything,” says Chhibber, who joined as a young art history graduate and left almost a decade later as his head of PR. “I think what we were experiencing was the tail end of a truly creative time, before the corporatisation of fashion. The budgets were really tiny and I think people would be shocked to know how little money went into the collection because it was so emotionally impactful.”

Two major patrons were Vogue’s Anna Wintour and André Leon Talley, both of whom had grand plans for Galliano. “John was sleeping in a sleeping bag on the floor of a friend’s house,” recalled Leon Talley to The Cut. Prior to this show, Galliano was forced to skip a season and after it, he lost his backer and his studio space, prompting Wintour and Talley to flex their muscles and make the world know that Galliano was Vogue-approved. “André would come by the studio every night with bags of McDonalds to feed everyone,” remembers Chhibber. After the show, Wintour organised a trip to New York for Galliano, where he met uptown society doyennes such as Anne Bass and Nan Kempner, marking the beginning of his couture clientele, as well as John Bult and Mark Rice from investment bank Pain-Webber, which put up $50,000 to stage the next show. Leon Talley persuaded Portuguese art and couture patroness, São Schlumberger, to lend her empty 17th century hôtel particulier as a venue and weeks before the show, Team Galliano were working from its decrepit kitchen on the now-iconic 17 bias-cut Japonisme-inspired looks (Osterhoudt remembers finding a 1970s disco, complete with lava lamps and leather booths, in the basement).

The Impact

Wintour’s most potent level of support came in the extensive editorial coverage devoted to Galliano in the March 1994 issue. Two major spreads styled by Grace Coddington and photographed by Ellen von Unwerth and Steven Meisel showcased the best of Princess Lucretia. ‘The Piano Lesson’, von Unwerth’s saturated ‘style essay’ was set on the sandy shores of Jamaica, complete with tulle-covered taffeta crinolines and chiffon blouses – an ode to the collection’s connection to The Piano. Meisel’s spread, however, was devoted to the altogether more shoppable and sinuous slip dresses, modelled by Linda Evangelista in a 1930s boudoir. “For once in my life, the pictures had been shot to look commercial,” says Galliano, “Not Dotty Duchess dresses but, like that silk jersey dress you have to have now. RIGHT now!” It ignited a demand for his bias-cut dresses, which Wintour credits as “a symbol of what women wore at night in the nineties, and that was John, completely John.”

What made Princess Lucretia so potent was the sheer romance and sincerity of it, due to Galliano’s magical marriage of narrative and craft. Just months before, one critic had described the ready-to-wear shows as so derivative that they were akin to necrophilia, and while other designers were experimenting with deconstruction and grunge-infused aesthetics, Galliano’s utter dedication to construction and beauty was a gasp of fresh air. “This really set the ball rolling for John to do couture,” says Mesh Chhibber. “This show had a couture sensibility that was really pivotal in placing him at Givenchy.” Within a year and a half Galliano was appointed as creative director at Givenchy, taking his die-hard couture clientele with him and becoming the first English couturier since the forefather of it all, Charles Frederick Worth – not bad for the son of a South London plumber. It heralded a new age of the designer as rock star, shaking up the ancien régime of couture’s discreet post-war culture and imbuing it with a sense of narrative, spectacle and theatre.