We explore the life, style and inimitable character of Girl of The Year, Warhol muse and Harmony Korine collaborator (Baby) Jane Holzer

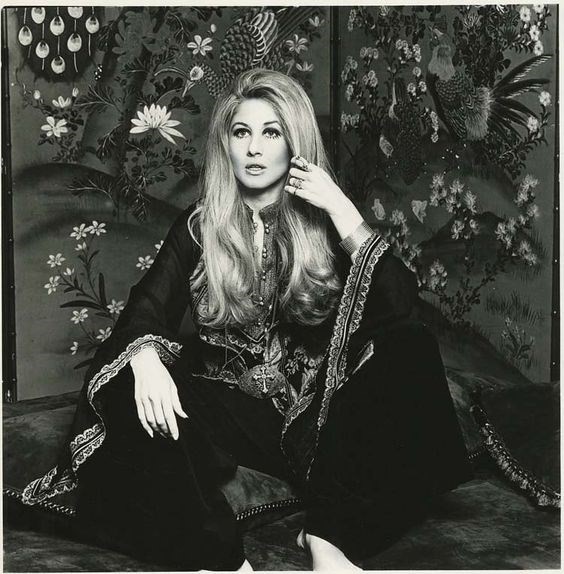

Profiling the Warhol Superstar “Baby” Jane Holzer in 1964’s The Girl Of The Year, Tom Wolfe is typically apoplectic. “She is gorgeous in the most outrageous way,” he howls – “her hair rises up from her head in a huge hairy corona, a huge tan mane around a narrow face and two eyes opened – swock! – like umbrellas, with all that hair flowing down over a coat made of…Zebra! Those motherless stripes! Oh, damn!”

This particular “Baby” was given her name at the age of twenty-two, when “Carol Bjorkman, a columnist for Women's Wear Daily, who used to write about me all the time, came up with [the nickname]. It obviously had to do with What Ever Happened to Baby Jane, which came out at the time,” Holzer shrugged, “but I’m not sure why Carol gave it to me. She had not seen the movie, and neither had I.” Either way, and perhaps because of her cherub’s face, it stuck. Before she became the girl mentioned twice by name in Virginia Plain, she was plain old Jane Bruckenfield – a property tycoon’s daughter born in Florida, educated and expelled in Connecticut (from a school called, perfectly, “Cherry Lawns”), and then finally liberated in New York City. Jane became not only Warhol’s muse, but also one of his major collectors; “I can’t explain it,” she shrugged. “He just speaks to me.” Later, she wrote him a note reading simply: You made me – love Jane.

“Baby Jane,” a correspondent for her hometown’s paper, The Palm Beach Post, suggests, “[was] a Holly Golightly for the Mod era, but with her own money.” At the tail end of the age of the debutante, she embodied the Real Thing of big-mouthed sexual freedom, so that Jagger’s lips were “diabolical,” and the very idea of feminine purity was “a lie to oneself.” Love, she suggested, could last forever, but might also last “four or ten minutes.” “Maybe it’s the Bomb,” she explained – “we know it could all be over tomorrow, so why try to fool yourself today?”

Defining Features

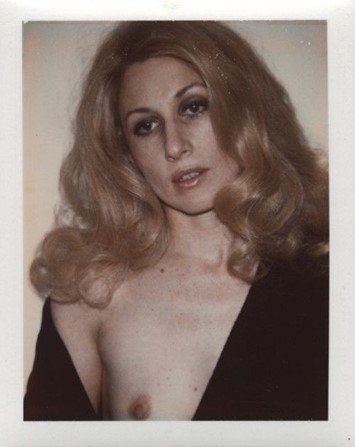

If the higher the hair, the closer to God, then Holzer was maybe less of a Superstar than a saint: per Wolfe, her bouffant is, variously, an “incredible mane”; “enormous”; “a ciliate corona”; “huge [and] hairy,” and “vast [and] tawny.” “She was a lovely young woman,” he later remarked, “but her loveliness came from excitement rather than perfect features. She thrived on excitement, and that just happened to fit the tenor of the age."

For her part, she described herself as: “I guess, just 1964 Jewish,” by which she meant a girl with the leonine, mod-ish beauty of Barbra Streisand and legs like a thoroughbred. Photographed slouching for Warhol in those “motherless” stripes, she’s an obvious icon: an Edie pre-Edie, whose towering hair isn’t engineered for showing-off as much as for taking up valuable space. Wearing a jumpsuit by Luis Estevez in the climactic party scene of The Girl Of The Year, Baby Jane —always seen and heard, simultaneously — can’t help but embody her own hot tomboy’s convictions. “It has huge bell-bottom pants,” the author notes. “She puts her legs together…it looks like an evening dress. But she can also spread them apart, like so, and strike very Jane-like poses.”

Seminal Moments

First recognised in the press for her parents’ Floridian real estate fortune, the speed of her progress from preppy to It-Girl to That Girl set heads spinning. What’s a nice heiress like Holzer, the New York media wondered, doing in a Factory like this? Or, worse: in movies like this, where all she’s required to do with that beautiful Palm Beach body is absolutely nada? Starring in ten of Warhol’s screen-tests, the best-known is one where she’s brushing her teeth in a manner so languid she might be on Valium; never before has dental hygiene appeared more seductive, or more soporific. “The bond between Baby Jane and Andy Warhol,” Nicky Haslam once quipped, “was either made in heaven, or else it was made in Chanel.”

Though not the first of Warhol’s Superstars, she is often described as the first to be actually famous, having being photographed by David Bailey for Vogue and, thus, “made overnight.” "Jane Holzer is the most contemporary girl I know," raved Diana Vreeland, calling her “a blaze of golden glory.” Later, shrugging off her “Baby,” Holzer turned to building her art-world reputation, acquiring work that – like its collector – is best described as ‘contemporary.’ “[I collect] Julian Schnabel, Richard Prince, Jean-Michel Basquiat,” she told Christies’ in-house magazine. “I love Andy [Warhol], and Les Lalanne. Justin Adian I like – also Nate Lowman, Dan Colen, Terence Koh, and Adam McEwen.”

She’s AnOther Woman Because…

Asked by Andy Warhol whether she wanted to “be in the movies” while walking down Lexington Avenue, Holzer deadpanned: “It beats the shit out of shopping at Bloomingdale’s every day.” Wolfe has it right: “Oh, damn!” A sometime-producer, backing films like Héctor Babenco’s Kiss of the Spider Woman, Baby Jane Holzer was also instrumental in bringing the only four Girls Of The Year who really mattered in 2013 to the screen: Britt, Candy, Cotty and Faith, the stars of Harmony Korine’s sick, neon State Of The Union Undressed, Spring Breakers.

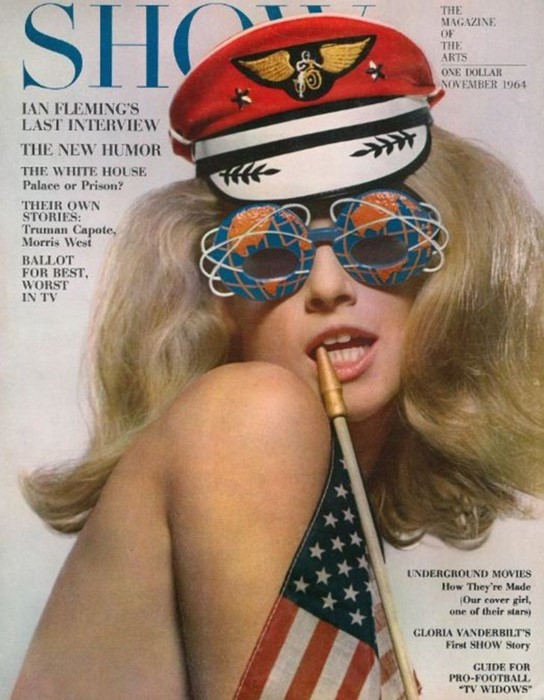

Running wild in Jane’s native Florida, all four are exciting and excited rather than picture-perfect; like her, they’re gorgeous in ways that are mostly outrageous. Proving that American dreamgirls beget American dreamgirls, long before Franco was heard to hiss thissss is theeee Amuuuricaaan Dreeeam, y’aaaaallllll in Harmony’s movie, Baby Jane – the film’s Executive Producer, at 71 – was in Show magazine: “barebacked, wearing a little yacht cap and a pair of ‘World’s Fair’ sunglasses, holding an American flag in her teeth.” “Girl Of The Year?” asks the closing line of Wolfe’s profile, having first described her rowdy entrance into a nightclub. “Listen: they will never forget.”