In the wake of Vivienne Westwood’s death, we explore the eclectic and revolutionary history of Westwood’s iconic London boutique, situated at 430 Kings Road, Chelsea

A version of this article was published on 12 May 2016:

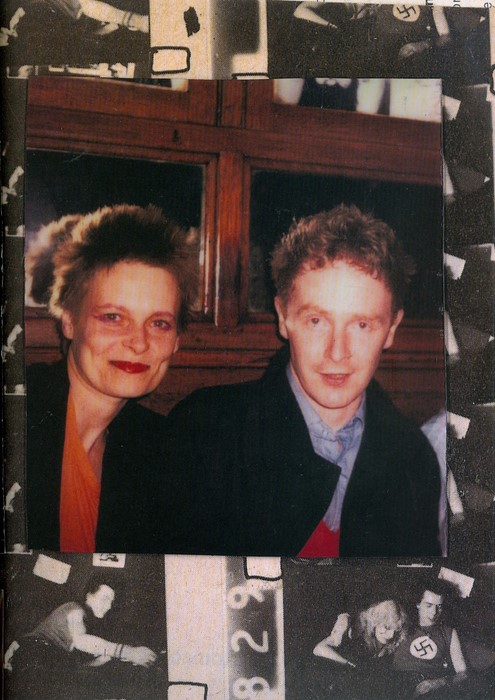

In October 1986, when asked about the plans for her S/S87 collection, Vivienne Westwood told The Face, “I’m using my shop as a crucible. The stuff that’s in there is what will sell elsewhere… It’s kind of market research…” Westwood and her then partner Malcolm McLaren had opened their first Chelsea-based boutique in 1971, and it operated not only as a testing ground for global sales, but as a location of diverse and famed retail incarnations, selling the uniforms of socio-economic rebellion.

“Malcolm and I changed the names and décor of the shop to suit the clothes as our ideas evolved,” Westwood explained in her 2014 memoir. Between 1971 and 1976, their boutique operated under the names, Let it Rock, Too Fast to Live Too Young to Die, Sex and Seditionaries, before being reinvented as Worlds End in 1979, a title the store still holds today.

In the mid-70s, Westwood and McLaren’s punk clientele would be accompanied from Sloane Square Underground Station to Worlds End by police escort, a route lined today with homogenous and upmarket clothing chains and eateries. Situated at a kink in the Kings Road, against a backdrop of 70s Brutalist council housing, here we explore the history of Westwood’s evocative retail reinventions, with insights from those who experienced them first hand.

Let it Rock

In 1971, Trevor Myles, owner of Paradise Garage, a boutique located at 430 Kings Road, rented the back of his store to Vivienne Westwood, then a primary school teacher, and her boyfriend Malcolm McLaren, a recent art school drop-out. A purveyor of used denim and Oshkosh dungarees, Myles owed money to the retail entrepreneur and previous owner Tommy Roberts, whose American rockabilly boutique Mr. Freedom had sold Mickey Mouse-print T-shirts, ice cream-appliqued dresses and kitsch symbols of post-hippie escapism.

After the opening of Mary Quant’s Kings Road shop in 1955, Chelsea boutique design had become synonymous with opulence and experimentation. At the marijuana-heavy hangout Granny Takes a Trip, a 1948 Dodge saloon had been installed into the shop’s façade, as if crashing through the front window, while at Mr. Freedom, a bright blue stuffed gorilla stood in the shop window.

“At the time there were lots of couples that we knew that had shops,” explains Michael Costiff, founder of the famed West End club night Kinky Gerlinky, and who had a café in the Chelsea Antique Market in the early 70s. “Celia Birtwell and Ossie Clark were up the road and our friends Jeff and Pam had a shop over Battersea Bridge selling Hawaiian shirts.”

Preoccupied with American 50s culture, Westwood and McLaren began selling rock ‘n’ roll records and kitsch memorabilia from their back room marketplace. They took over the lease of the store later in 1971, painting the Chuck Berry song title Let it Rock onto a black corrugated façade in fluorescent pink letters. They furnished the store like a 50s living room littered with porno mags, and, interested in the subversive aesthetics of Teddy Boy revivalists, began selling brothel creepers and zoot suits finished with velvet by the tailor Sid Green.

Too Fast to Live Too Young to Die

Westwood and McLaren replaced the decaying façade of Let it Rock in 1972, renaming the store Too Fast to Live Too Young Too Young to Die, an epithet worn on the motorcycle jackets of American bikers, to honour the death of James Dean. Emblazoned with a menacing skull and crossbones, the façade of the store heralded a darker interest in rebellious rocker aesthetics, and one more nihilistic than the nostalgic escapism of their 50s-style store, decked out with a jukebox, Odeon wallpaper and posters of Billy Fury.

Inspired by McLaren’s anti-capitalist and Situationist politics, Westwood began customising sleeveless black T-shirts with inflammatory slogans, spelt out in safety pins, glitter glue and bleached chicken bones. ‘PERV’, ‘ROCK’ and ‘SCUM’ (an acronym of the anarchic group led by Valerie Solanas) T-shirts, were stocked alongside black drainpipe jeans and vests with zips covering the nipple, while the original Let it Rock label still catered to the Edwardian styles of Teddy Boys. “I was too young to be a hippie and too old to be a punk, but I was very much into the fashion side of it,” explains Costiff of Westwood’s DIY aesthetic. “In a funny way, you became part of a little club.”

SEX

In 1974, shop assistant Glen Matlock, and the future bassist of the Sex Pistols (founded by McLaren in 1975), helped erect the pink rubberised letters of SEX, Westwood and McLaren’s most provocative retail incarnation. “I remember driving from South Kensington up and down the Kings Road as an 11-year-old and seeing that sign outside,” explains Murray Blewett, Head of Archive at Vivienne Westwood, who has worked at the label since its seminal A/W87 Harris Tweed collection.

After a month of renovations, the store’s interior had been covered with a spongy womb-like material sourced from the Pentonville Rubber Company, the walls defaced with anarchic and phallic graffiti and displaying whips, chains and puckered rubber skirts. SEX was presided over by the punk icon Jordan, clad in bondage gear and Mondrian style make-up, and Bella Freud, Chrissie Hynde and Alan Jones all worked there as shop assistants. Jones was even arrested for public indecency after wearing a provocative Westwood T-shirt of two Cowboys exposing their penises down the Kings Road.

“Jordan would call my wife Gerlinde and I when she had new things in,” explains Costiff, who sold nearly 300 Westwood items to the V&A in 2004. “She’d tell us all the funny things that had gone on in the shop, like businessmen trying on rubber behind the screen, and then we’d hang out at the little Golden Triangle of pubs round there – The Water Rat, the Man in the Moon and the Roebuck, and later we’d watch Adam and the Ants and X-Ray Spex performing upstairs. The scene was actually extremely small; the population was a lot less then.”

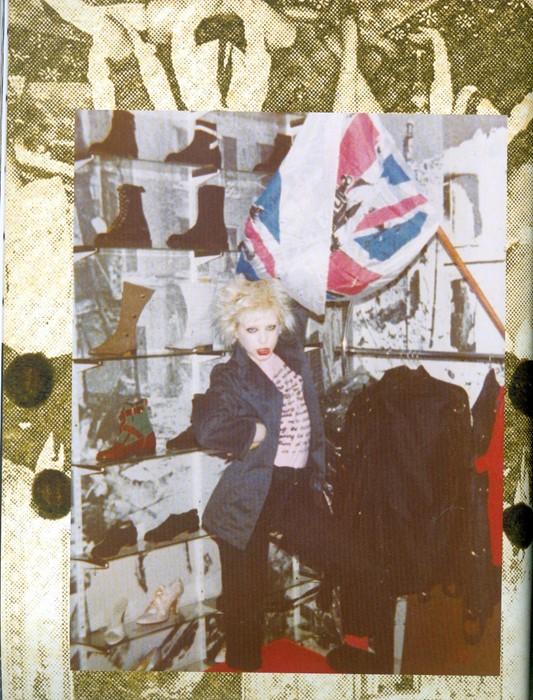

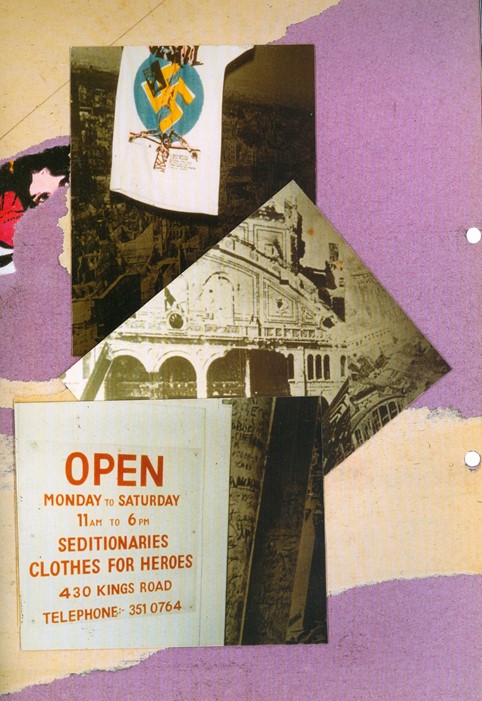

Seditionaries

“The store was kind of disposable in a way. Vivienne and Malcolm would pull out one thing and put in another,” explains the architect David Connor, who took over the design of Seditionaries from Ben Kelly in 1974, his first commission after graduating from the RCA at age 26. With an intimidating opaque façade and an interior depicting the air-raided scenes of Dresden, Seditionaries was the ultimate rejection of West End consumerism, a topic that McLaren had explored in his unfinished 1970 film Oxford Street, and which was listed as a hate on Westwood’s ‘hates’ and ‘non-hates’ T-shirt. “You had to be really brave to go through the door,” Connor explains. “We put white glass in the front windows, so that you couldn’t see inside… Some people actually thought it was a betting shop.”

“Seditionaries was an outreach everyone wanted to reach… Siouxsie Sioux and all of the icons of the day would hang there,” explains the renowned Blitz DJ Princess Julia, who saved her wages from Crimpers hair salon aged 16 to buy Westwood pieces. “It brought clothes that were about sex to the street… the zips and buckles of Westwood’s bondage trousers were really suggestive and fetishistic, except that they were made out of cloth, lightweight for the summer and heavier for winter… There was a real inventiveness going on, if you could only afford one Seditionaries item, you could make things out of sink plungers and plugs and chains and mix them all up.”

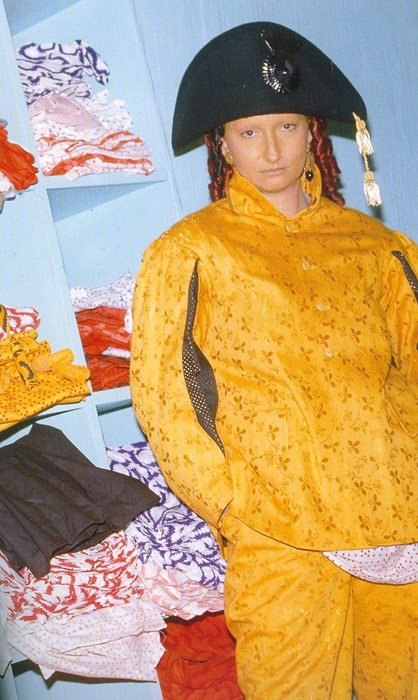

Worlds End

In 1979, Westwood and McLaren’s store was reinvented as Worlds End, a name taken from the area of Chelsea it is located in, viewed in the 18th century as being on the very outskirts of the city. “Even at the time, people didn’t really walk much further than the Old Town Hall, which was about halfway down from Sloane Square,” Costiff explains.

“We decided the store was going to challenge time and space, which is an amazing concept for a tiny shop,” says Connor, who also designed Worlds End. With a slanted floor like the galleon of a ship and a façade featuring a 13-hour clock ticking backwards, the store reflected the whimsy and historicism of Westwood’s A/W81 Pirates collection, the first to be sold in its new iteration. “Originally I came up with this idea that you’d walk through two sheets of glass filled with smoke at the entrance, like a dream sequence in a film, but we realised all the smoke would go up the Kings Road,” he explains. “The sloping floor really challenged the horizontal… The shop assistants actually got bad backs from working on the slope, so we had to put a flat section behind the cash till.”

In 1984 Westwood and McLaren separated, and Worlds End was closed, with Westwood moving to Italy to work on the production of her label with Carlo D’Amario. Blewett was working at the punk boutique BOY when news spread in 1986 that Worlds End had reopened. “The Kings Road still had the boutique American Classics and the Great Gear Market, but it was feeling a bit lacklustre,” he explains. “We heard something was going on at Worlds End… there didn’t seem to be any electricity but there were candles and hats in the window. Vivienne’s mum was working in there, and they were selling pieces from her S/S85 Mini Crini collection. I purchased a suit, which Vivienne personally fitted on me. You kind of wore those clothes as a badge of honour, they made you feel heroic.”

Today Westwood devotees flock to Worlds End to invest not only in her Gold Label pieces, but in recommissioned archive classics, from Buffalo hats to Keith Haring-inspired squiggle tops, cowboy T-shirts to tartan bondage trousers. Its name is now a reminder of Westwood’s environmentalism, and her Climate Revolution T-shirts hang amongst other historic designs, made using organic cotton in Peru. “Worlds End will never change,” Blewett explains. “There was a lot more fantasy and fun in the old days and Malcolm and Vivienne followed in that great tradition. In some ways the store is the last one of its kind.”