As far as fashion shows that double as cultural milestones go, John Galliano has had his fair share – but perhaps the most notable is the spirited, salon-style offering that took place twice on March 5th, 1994 at São Schlumberger’s Hôtel Particulier. Today, it’s fashion folklore: the moment that an impoverished, poetic David triumphed against the seemingly impenetrable Goliath that was Paris’s megawatt fashion industry. In reality, it was a last-minute culmination of like-minded creatives that established Galliano as perhaps the most seductive, skilled and subversive storyteller of an era, something that would eventually take him to dangerously high heights. Often described as ‘back from the brink’, this show was less of a comeback (Galliano has had several, let’s not forget) and more of a statement of future promise: this is what we can do. Just as Carmel Snow christened Dior’ wasp-waisted, full-skirted vision of post-war femininity as the ‘new look’, André Leon Talley coined the term ‘fashion moment’ on March 5th, and the rest is history.

The previous season, Galliano had electrified Paris with a collection that evoked Tolstoy in its heart-racing theatricality and narrative – but, as ever, his pet historicism was laced with a subversive sense of wit and sexuality. Despite the critical acclaim, however, Galliano and his team were without a studio or a penny to produce another collection, and had resigned themselves to the fact that wouldn’t be able to... cue Anna Wintour. Galliano’s most potent patroness stepped in and did what powerful women so often do to get the ball rolling: she organised a lunch. Over Portuguese sardines, André Leon Talley (Wintour’s man on the ground) and Galliano asked São Schlumberger if she’d be prepared to lend her empty 17th century Rue Ferou mansion, which was supposedly built for D’Artganan, one of the Three Musketeers, and later inhabited by Mademoiselle de Luzy, a demimondaine actress and mistress of Talleyrand. In the 70s, Schlumberger threw legendary parties in the hidden disco basement, complete with leather booths and lava lamps, which remained deserted there decades later. “Why not?” she responded, “just give me some time to have my eyes touched up a little bit.” Wintour and Leon Talley also secured $50,000 from Pain Webber’s John Bult and Mark Rice, armed with Steven Meisel’s photographs of the designer’s bias-cut dresses over lunch at the Bristol Hotel.

Away from a plain white runway, Galliano seized the opportunity to create a spectacular mise-en-scène of faded grandeur and aching romanticism. He sourced hundreds of rusty old keys from the flea markets at Clignancourt, each one of which was turned into an invitation with a tea-stained and flame-frayed handwritten note. The set was equally spectacular. “We opened the windows, brought in tons of dead leaves to scatter around, filled fallen chandeliers with with rose petals, created unmade beds and carefully placed upturned chairs at various points,” Galliano recalled in Colin McDowell's Galliano. “We filled the house with dry ice so that the whole place had a desolate, poetic look, like a Sarah Moon photograph. We lit the house from the outside to give it an early morning dew feel. The girls worked the whole house from the top floor down. It was like an old salon presentation. Gorgeous creatures with heavenly, heady make-up wandering through this deserted house, bending down and looking for abandoned love letters in the dust … it was magic.”

The Show

The story picked up where the previous season left off. After the war, Princess Lucretia returns to Paris a widow, as her husband had died in combat. Her pastel-hued innocence has matured into broodingly smoky darkness; Princess Lucretia is now a night creature of 1920s Paris, with the noire slips, furs and kimonos to show for it. Of course, this all began with a bolt of black satin-back crepe, inexpensive, lightweight and lending the illusion of two different fabrics. Galliano had already made a name for himself with his bias-cut dresses, which drew on the technique that Madeleine Vionnet pioneered in the 1920s. His cutting, however, was subtly spectacular: seams would take the shape of scallops, stars and spikes as they sinuously travel around the body, only noticeable to the eye in close proximity. “Before you hem them you have to let them hang for a week,” explained Galliano. “After you wear it for about half an hour, your body temperature breaks down the fibres of the fabric.” Hence, Galliano and his team would rub the girls down just before they went on the runway so that the dresses would be moulded to the shape of their body.

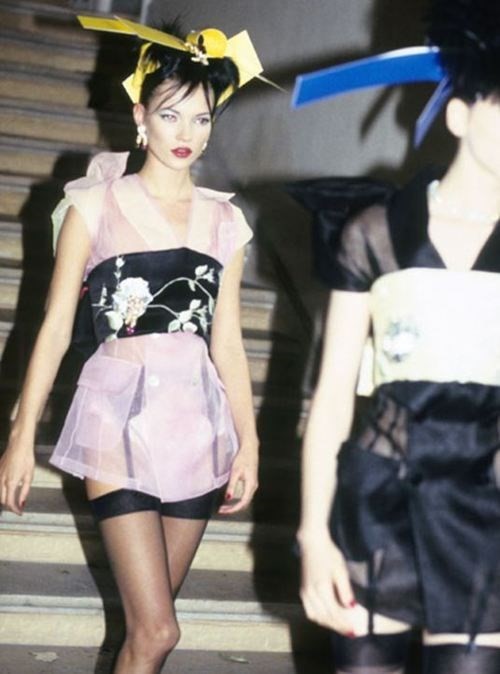

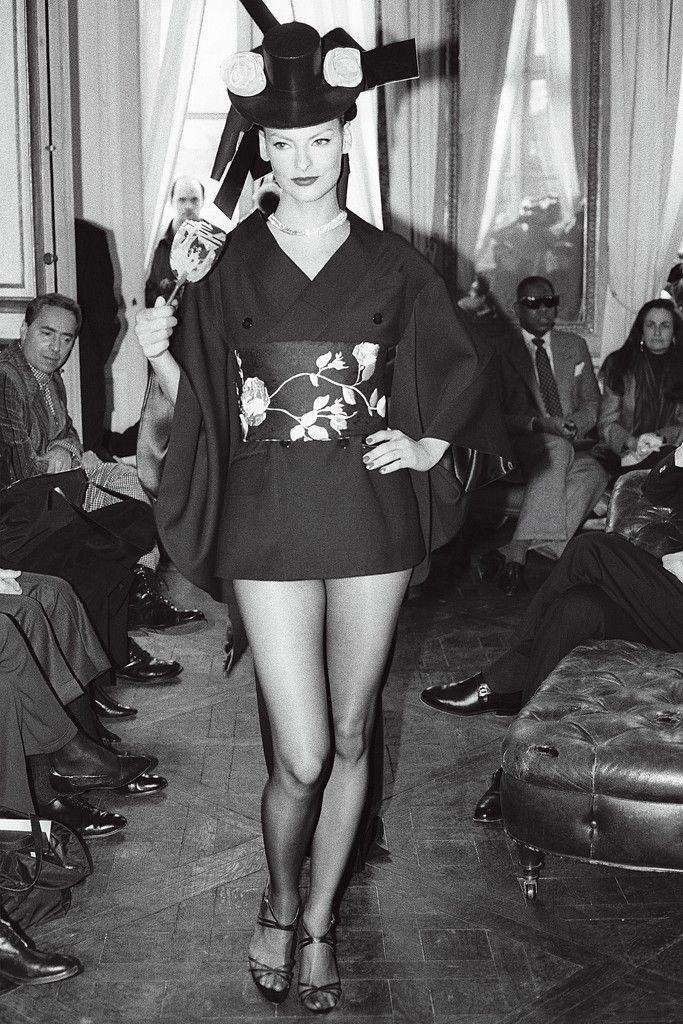

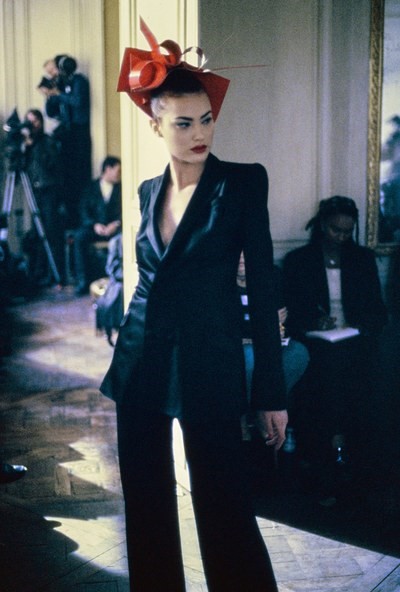

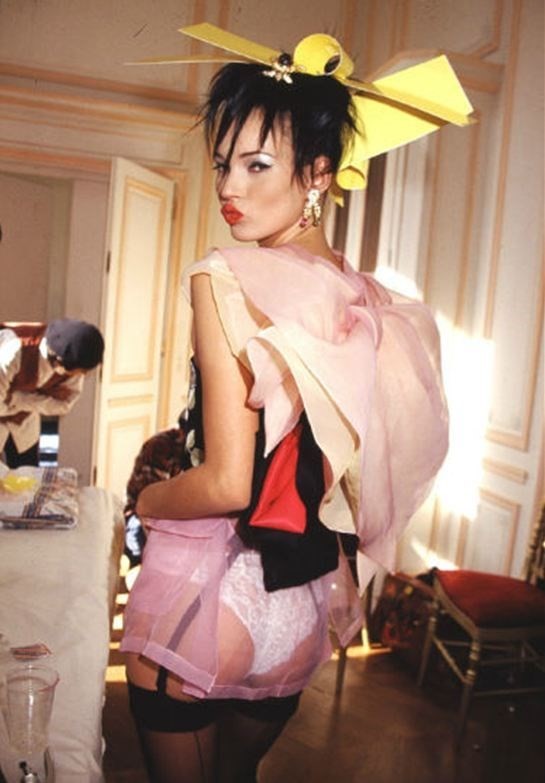

The collection itself was a study of Kiki de Montparnasse, a beacon of 1920s sex appeal, and the occidental fantasy of the Orient as a fertile land of erotic-exotic impulses. Slinky slip dresses worn with stockings, 40s smoking jackets and micro-kimonos fastened by rose-embroidered obi belts, top-heavy portrait collars and Deco shearling jackets topped with Stephen Jones’s cloche hats, elevated by Place Vendôme diamonds, and grounded by Manolo Blahnik’s silver and black strappy sandals. Throughout, the black was accented by Kabuki pink and yellow. Galliano had always been inspired by the Japonisme and Chinoiserie that permeated fashion and the arts at the beginning of the 20th century. Galliano’s dear collaborator, Amanda Harlech (née Grieves) called the muse an “oriental kittenish princess.” Paul Poiret and Madeleine Vionnet, both major influences on Galliano, were two of the first Parisians to incorporate the kimono into their designs, borrowing from the characteristic arch over the back, the collar falling back to reveal the nape, and the asymmetrical hem, which is shorter at the front and longer at the back. Galliano’s vision, however, was distinctly untraditional – stockings and seams elongating lithe legs, embroidered obi belts double as corsets and bandeaus, and tailored smoking jackets masquerade as mini dresses.

The People

Stephen Jones, who had spent almost a decade as the milliner for “ruthless modernist” Claude Montana, began working with Galliano the previous season and found joy in the designer’s sense of historicism. For the show, he created black hats inspired by Schiaparelli and Lucille Ball, which sat alongside sharp, Möbius-like plastic headpieces by Julien D’Ys. Jennefer Osterhoudt, Galliano’s then-assistant who now runs a Hackney-based archive of Galliano, McQueen, and Givenchy (by both of the designers), remembers the dramatic story of D’Ys’ involvement. “He arrived so late with all of his Japanese assistants dressed in black,” says Osterhoudt. “As soon as he got there, he was leaving and everyone as freaking out – the show was supposed to be starting in about 20 minutes. He and his assistants all went to the stationary section of BHV [a chain of Parisian department stores] and bought all of these bright blue, green, red, and yellow plastic sheets. They came back and started cutting them into strips and then he begins rolling them up and takes a match to make a small hole. Then, he slides in a hair pin and begins linking them all together to make these sculptures in the hair.”

The result was a perfect balance of Japanese modernist synthetics and Jones’ ornate millinery, creating a sort of modern-day Japonisme that subverted the 40s tailoring and intricate embroideries. Galliano also wanted real diamonds, so Amanda Harlech went to Place Vendôme to persuade Paris’s leading jewellers to loan pieces for the show. They arrived with countless bodyguards, who waited on the top floor, but Harlech mixed and matches pieces from different houses on each of the girls, a faux pas that resulted in complaints from the jewellers and a number of confused bodyguards. The models were also a major coup: Linda, Kate, Naomi, Christy, Helena (the girls who still don’t need a surname and famously didn’t wake up for less than a small fortune) all walked for free, not once but twice, as there were two shows; one in the morning and one in the afternoon. Jones remembers that what really gave the girls a fluid, liberated sense of movement was the music. Puccini was nowhere to be heard – instead, Jeremy Healy played a set of Nirvana, Slo Mushun, Vangelis, and James Brown.

Christy Turlington (whose ‘birthday cake’ dress was being finished by Bill Gaytten as the show started) and Kate Moss were the only models to wear colourful designs. Moss’s bubble-gum pink organza kimono was inspired by an interlude between Lieutenant Pinkerton and Madame Butterfly, with the open bell sleeves pulled to the back and tied in a knot, an idea that came from photographs of Palestinian women making bread and tying their sleeves behind them. Nadja Auermann elegantly skulked through the rooms, cigarette in hand, like a Weimarian vixen, wearing a black micro slip and an upside-down shearling jacket, a felt cloche shadowing her face and pinned with a diamond cow-parsley sprig – a look that Hamish Bowles says defined the moment.

The Impact

“Fashion editors who can count great fashion moments on one hand probably use three of those fingers for John Galliano's unforgettable shows,” wrote Amy Spindler in The New York Times, three days after the show. “Though his show on Sunday lacked large-scale theatrics, Mr. Galliano's work was taken seriously by the press and by store buyers.” When asked how much Bergdorf Goodman would be buying, the department store’s fashion director, Ellin Saltzman, committed to all of it, right there and then. There was also the couture clientele that Galliano had amassed: doyennes such as São Schlumberger, Anne Bass, Dodie Rosekrans, Nan Kempner, Lee Radziwill, Béatrice de Rothschild, and Isabelle d’Ornano. Having ‘escaped’ the attic of the Plein Sud studio, where the team was previously based under the patronage of Faycal Amor, Galliano secured a studio in the Passage du Cheval Blanc, just off the Place de la Bastille. It was all thanks to John Bult and Mark Rice, who decided after the show that it was time for Galliano to become a proper company with a proper studio. They owned 75% and Galliano owned 25%, but it was enough to seriously elevate production and time management. “Suddenly, I had my first Paris atelier, and these fab couture ladies were ordering from this Dickensian building!” recalled Galliano years later in Vogue. “The look then was very ragged and unfinished, but I was obsessed with couture-like finishing – I wanted the garments to look as beautiful inside as out.”

With his arch romanticism and inherent pleasure in subverting it, Galliano elevated his beloved historicism far beyond the realm of period costume, seamlessly combining the world of rarefied skill and tradition with a knowing wink to contemporary culture – haute couture for Generation MTV, if you will. “John would have the big romantic dream, Stephen [Robinson] would make it sexy and fun and give it some humour, and Bill [Gaytten] was the master of technique,” says Stephen Jones of what he calls the “holy trinity.” Not before long, all of those power lunches, fabulously creative DIY solutions, sleepless nights, and improv production finally paid off. The three of them took Paris’s couture salons by storm, with Galliano becoming the first English couturier since Charles Frederick Worth, the craft’s forefather – not bad for the son of a South London plumber. It marked a new era of theatrical presentations and colourful themes that took in a blend of high and low, shaking up the ancien régime of couture’s discreet post-war culture and giving big ideas even bigger budgets. Galliano’s couture shows became cinematic productions, entertaining spectacles ripe that inspired some of the great interpreters of fashion, from Irving Penn to Grace Coddington, to create some of the most visually arresting images of contemporary design. That’s what makes this pivotal show more than just a fashion moment.