From mid-Renaissance dressing to the runways of Christian Dior and Balenciaga, we trace the style evolution of 'trying not to try'

If the fashion industry has ever been consumed by a single ideal, the concept of 'effortlessness' might well be a contender. Terms like 'the natural look', 'minimal simplicity', and 'off-duty wardrobe' are now comfortably nestled amongst the fixtures of fashion copy, while casualness has found yet another footing in the likes of 'normcore' (which has itself escalated into myriad offshoots) and the elevation of streetwear and hoodies (see Vetements, and now Balenciaga). Even displays of lavish excess can speak more about effortlessness than effort: as the 90s Galliano model glid down a marble runway, bedecked in couture, gently pelted by the precipitation of a thousand or so orchid petals, it was with an expression of exaggerated boredom, of nonchalance – as if to pass the whole affair off as the mere work of moments. The spirit of said nonchalance, which suffused 90s style from grunge to postmodern irony, has become a vital component in the language of fashion. Indeed, studied naturalness is so salient a feature of the contemporary fashion palette that it can often appear to have just...appeared. Instead, this apparently modern appetite for the 'natural' can be directly traced all the way to the Renaissance where its cultivation was considered paramount.

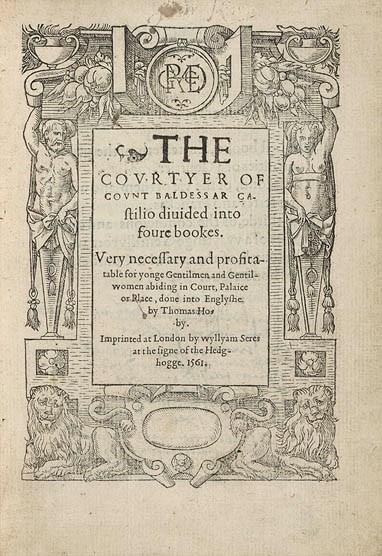

The Book of the Courtier

Holy Roman Emperor Charles V had three books at his bedside: the Bible, Machiavelli’s The Prince and Baldesarre Castiglione’s The Book of the Courtier. Published in mid-Renaissance Italy, The Book of The Courtier serves as the genteel literary foil to The Prince in many respects. Both were intended as instructive works, but Castiglione’s writing largely eschewed politics and princedoms for manners and style. The book was, in essence, a how-to guide in tact, charm and charisma, including instruction on how to sit on a horse, suitable attire, hairstyles and make-up, as well as how to speak and hold oneself. All of this was brought under the guiding principle of “sprezzatura”. Having no direct translation the word is often conveyed as 'the art of concealing art', 'the art of trying not to try', or simply, 'a certain nonchalance'.

One was meant to be gifted in multiple fields, from beauty to archery, but could not be seen as showing off these attributes; thus make-up was to look non-existent, courtiers were to be honey-tongued diplomats without recourse to overly virtuosic rhetoric, and clothes were to be flattering but without ostentation. This latter was particularly significant in the Renaissance, when attire was a conduit of status. Showing this status to one’s advantage was common practice, but sprezzatura ushered in a different approach to dress. Rather than a mere signifier of wealth or class people began to think of clothing in terms of something more subtle: a means of influence and manipulation; a key to social advancement. It marked the beginning of a heightened self-consciousness about fashion and its capabilities.

The Cult of the Courtier

The book and its tenets were a sensation, with sprezzatura flooding the courts of Europe in various forms. One of its most prominent adherents was to be found in the painter Raphael. Though nowadays considered highly mannered, his attempt at instilling sprezzatura into his work was a significant break from the earlier formality of pictorial composition. Castiglione’s volume was famously considered vital reading by Roger Acham, the tutor of Queen Elizabeth, and its lure over the Elizabethan court was so effective that it very quickly became embroiled in aristocratic life as well as the arts. In depictions of courtiers throughout Europe (as with Raphael) we see a shift from the typical polished figure to something altogether less immaculate. Bronzino’s Portrait of a Young Man is often cited as embodying Renaissance sprezzatura. Clad in black with little adornment, especially in the way of jewellery, the sitter emanates an apparent carelessness both through his indifferent gaze and assertive pose. All of these aspects are part of a highly manufactured attempt at flaunting the kind of nonchalance so idealised by Castiglione. It was also by way of such paintings that black became cemented as the ideal sprezzatura hue. It was favoured by Castiglione himself because expensive fabrics like velvet could be discretely worn, thus allowing for a display of taste and position without excessive pageantry.

The Courtier in Denim

The eschewing of visible effort and labour to establish oneself in a privileged coterie was one of sprezzatura’s prime effects and the later attire of the leisured classes continued to reflect this. Sprezzatura was kept alive in upper-class societies for centuries, but it is in 19th-century dandyism that we see one its greatest parallels. Often synonymous in people’s minds with stylised decadence, the original concept of dandyism (as delineated by Baudelaire in his Painter of Modern Life) was more about regimental simplicity. A heightened concern for sartorial style combined with an aversion to labour and a (considered) indifference was directly inherited from the Renaissance mode.

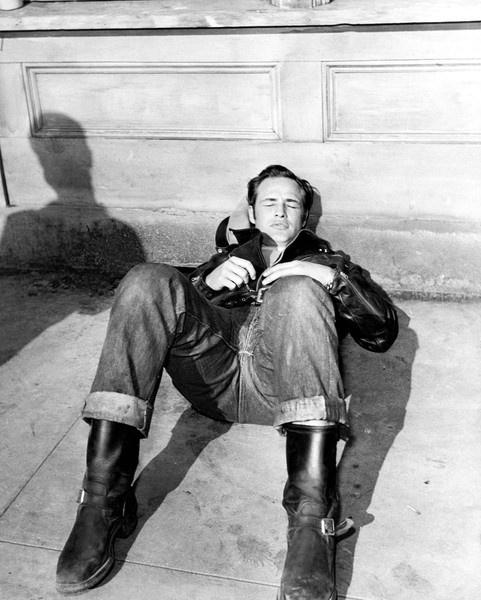

Interestingly, around half a century later it is through the appropriation of working class attire that sprezzatura is exerted. While originally a pronounced distancing from labour and the 'effort' it entailed was stressed, working clothes and associated fabrics became a way to show contempt for the sartorial conventions that now spoke too much of formality and thus too much of effort. This was most notable in Hollywood dress, as iconified by James Dean and Marlon Brando whose sporting of leather bomber jackets and denim in the public conscious was parallel to portraits of Renaissance courtiers with their sombre attire and aloof posturing.

Today sprezzatura is a term that is found on several blogs and men’s style guides. In most cases it has been reduced to a fashion buzz-word, or a 'look' which generally involves a bit of tweed and a loose scarf. As such the influence of this concept on contemporary style feels less palpable than it should: from the birth of casual wear to the association of black as a 'fashion colour', the spirit of sprezzatura has sculpted innumerable cultural connotations. It represents our collective phobia of appearing 'try-hard', our obsession with effortlessness; even fashion advertising still seems to parrot what Castiglione tells us about fashion: that it can influence your life, that it can seduce others, win friends and most importantly gain social advancement.