Fashion is often seen as a solitary pursuit. Our perception is of the designer as auteur, in the mould of Charles Frederick Worth, the first couturier who declared he had Delacroix’s sense of colour and composed a toilette as the former would a painting. Kind of Trilby and Svengali stuff, only Worth – or any one of the many other couturiers, both then and now – is the Svengali to legions of Trilbies.

Nevertheless, it’s something of a fallacy. By its very nature fashion is a collective effort – few are the designers with the skills, let alone the time, to create their clothes single-handedly. Granted, Azzedine Alaïa has been known to hand-cut and sew the samples for his catwalk collections, but generally designers employ ateliers of hired hands to help make the ephemeral into material. Christian Lacroix emphasised his lack of technical prowess, his dependence on an atelier who could construct his drawings exactly as he sketched them. Cristobal Balenciaga could not only create a dress from scratch, but did: each season, a single black dress would be made entirely by his hands. Myth-making says that said dress encapsulated the changes for the season as a whole. The other hundred-or-so outfits, however, were constructed by the skilled petite mains who peopled his atelier on the Avenue Georges V.

The Studio History

But ateliers weren’t just filled with stitchers. In the past, houses like Dior, Balmain, Lelong or Piguet were peopled with talented, eager and ambitious young designers, jockeying for position in crowded design studios. The best may be spotted, plucked and heaped with laurels. The fasted and highest ascendant was Yves Henri Donat Mathieu-Saint-Laurent, a former assistant who, at the tender age of 21, was appointed successor to Christian Dior following the maître’s death in October 1957, aged 52. He seemed slight and unprepared for the weight of the role – but unbeknownst to the world, many of the later creations under the name Dior had come from Yves Saint Laurent’s hands. In hindsight, they are characterised by a youthful verve and light construction, albeit still in the vein of the founder.

Dior himself had been born from the studio system also: first working for Robert Piguet, then from 1942 for Lucien Lelong, head of the Chamber Syndicale at that point and helming a studio that produced works under his name, but by multiple hands. As with Saint Laurent later, the job of the studio designers at Lelong – the most notable being Pierre Balmain, as well as Dior – was to bring a sense of the new to a well-established name, to help titillate and excite clients, whilst operating under a known mark of quality. Examine Dior’s clothes for Lelong, and you already see sketched out the nascent lines of the collection that would come to be known the “New Look.” Dior’s shoulders were rounded rather than squared, his hips soft, his skirts fluttering as full as wartime restrictions would allow. They are a conservative wink towards the revolution in cloth he was ready to unleash.

Currently, Dior is again overseen by members of the studio: Lucie Meier and Serge Ruffieux, a pair of youthful designers operating under the imprimatur of former creative director Raf Simons’ modernist template. Their role is to carry Dior along safely to its next designer. Their latest collection glanced back to the immediate post-war years, an echo of the New Look, but equally redolent of Dior’s work at Lelong, the hazy outlines that would only become crystallised on February 12, 1947. Incidentally, garments designed by Dior under the Lelong label were on display as part of The New Look Revolution, an exhibition staged in Dior’s childhood home in Granville last year, chiming with the 110th anniversary of his birth. The women clad in Dior pre-Dior, watched couture mannequins dressed in Dior’s flowing, flower-women couture. The former were necessary to lead to the latter.

A Cruise Revival

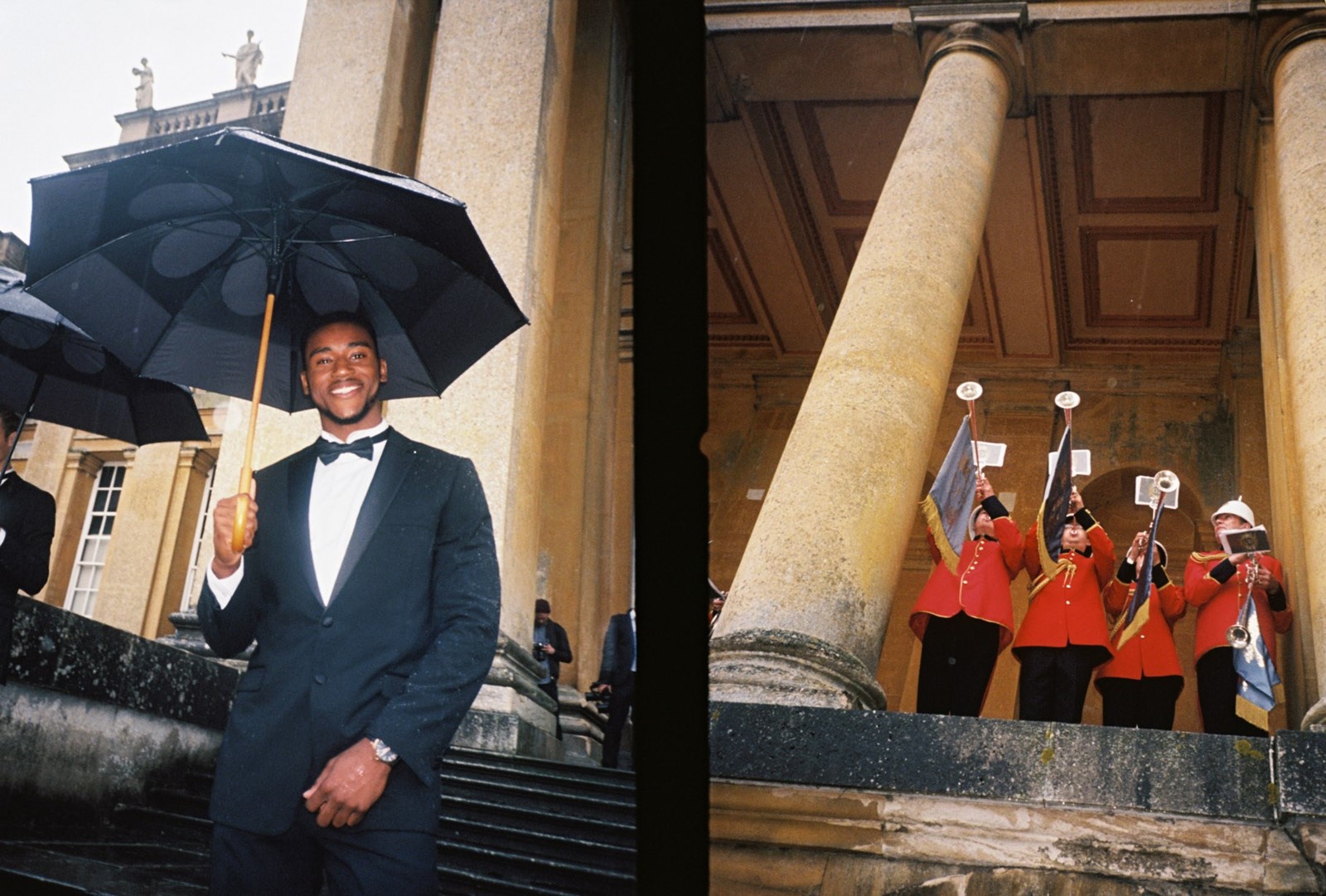

Dior’s latest outing, for Cruise, took place at Blenheim Palace, directly linking the Dior of today to the past, and to the notion of many studio hands making light work of the collection. The mythology of the singular creative has been shattered; fashion design is now acknowledged as a joint and cumulative activity, from conception to completion. Indeed, in Dior and I, Simons threw open the curtains, revealing the teams working on his haute couture debut for the house not only in the ateliers flou and tailleur, but in the design studio. And for collections like Cruise, where multiple markets demand multiple weights, designs, ideas and even identities of a mammoth house like Dior, the plurality of voice offered by a design team in place of a singular creative director can enhance the collection, particularly commercially.

It helps having a single theme to hang everything off of, though – in this case, the notion of Dior coming to England, which inspired Meier, Ruffieux and the rest of the Dior studio to examine notions of Britishness, from hunting scenes (as painted, say, by Stubbs or George Henry Laporte) to the nominal notion of the “English Eccentric”, like Edith Sitwell or Nancy Cunard and her stacked ebony and brass bangles. Perhaps that’s why, bar the Bar, there was no singular silhouette on show at Blenheim - no “H” line, as Dior showed in 1954, nor Yves Saint Laurent’s “Trapèze” - but rather a multitude of profiles and approaches, a collective collection, something to appeal across the board, to every woman – and the everywoman. This Dior show was a group effort and, as so frequently attested in fashion history, it would seem there’s a strength to be found in numbers.