When charting the rise of Italian fashion over recent decades, it is impossible not to include Pitti Immagine. While it is the National Chamber of Italian Fashion (or, more accurately, Camera Nazionale della Moda Italiana) which is responsible for staging the fashion weeks in Milan, thus building up the businesses of myriad Italian powerhouses, since the early 1950s Pitti Immagine has focused on disseminating the message of ‘Made in Italy’ from their base in Florence through a series of sprawling tradeshows. Pitti Uomo, founded in 1972, is undoubtedly the flagship event, held twice a year immediately prior to Milan men’s fashion week, and based in the Renaissance-era military complex of the Fortezza de Basso. This is where traditional codes of menswear are asserted, both through the tailoring houses and conventional sportswear and casual-wear brands that showcase new collections at elaborately staged stands, and through the hordes of impeccably turned out men who promenade through the fair.

As a contrasting foil to the tide of three-piece suits, pocket squares and perfectly arranged cufflinks, Pitti Uomo has also hosted many visionary designers over the years, offering them the opportunity to present their new collections against a backdrop of Florence’s rich abundance of palazzos, statuesque gardens and impressive architecture. Memorable Pitti designer projects have included Thom Browne, who once had rows of uniformed male secretaries typing away inside a polished mid-century office recreated inside the Istituto di Scienze Militari Aeronautiche, and the debut of Haider Ackermann’s menswear, which trailed with rich fabrics inside the courtyard at the Palazzo Corsini, as those watching reclined on chaise longues. These ‘happenings’ occur at a pace that suits Florence’s postcard city vibes; while brisk business is negotiated inside the Fortezza, designers such as Gareth Pugh, Rodarte and Thomas Tait use Pitti as an opportunity for more languid creative freedom.

This season, the 90th edition of Pitti Uomo announced a double whammy headline billing of Gosha Rubchinskiy and Raf Simons (it was Rubchinskiy’s Florentine debut, but Simons’ fourth appearance at the fair). If there are questions currently swirling about the validity of menswear shows, with the current industry shift towards consolidated mens and womenswear presentations and the constantly in-flux sittings of creative directors, then on the evidence of their latest edition, Pitti Uomo responded with a resounding vote of confidence.

Be in My Menswear Gang

The style crowd at Pitti Uomo is, shall we say, specific in its attire: a Borsalino hat is never perched out of place, the colour matching of socks to brogues is of paramount importance, and the waistcoat is omnipresent. These are the so-called ‘Pitti Peacocks,’ men who parade around the Padiglione Centrale main area inside the Fortezza, eagerly papped by hordes of street style photographers who are on permanent lookout for that perfect man-gang group shot. Nowhere else is the delineation of menswear style genres so apparent as it as at Pitti Uomo. But, that said, the fair welcomes menswear gangs of all aesthetics. As well as the suited and booted, this season saw Japanese cult king label Visvim, designed by Hiroki Nakamura, draw in crowds dressed in its signature Japanese patchwork boro and Native Americana-blended clothes. Fausto Puglisi set his own agenda for his menswear gang by presenting a homoerotic casting of beefy clubbers, looking ‘hench’ as modern Greek gods in Italia 90 footie shirts and loud prints. And of course, the Gosha-heads and Raf-addicts were also out in force. There’s a tribal mentality that has always been present at Pitti Uomo, but this season the diverse array of style tribes felt like a snapshot of menswear’s current state.

Gosha’s Message About Europe

While not directly related to the prospect of Brexit in the UK, Gosha Rubchinskiy’s all-encompassing presentation – his largest yet – felt exactly like the fashion tonic we all need as the debate dangerously spawns divisive language of “them” and “us”. “It’s about Europe now,” explained Rubchinskiy after staging his show at a brutalist tobacco factory. “This is the time when people need to collaborate and connect with each other, because we have the internet – everyone knows what’s happening around the world, so it’s stupid to be isolated. Let’s try to find words and ways to speak and live with each other.”

So what does Gosha Rubchinskiy – a Russian-based cult menswear label – become, when transposed to Italy? If in the past Rubchinskiy’s work has been lazily tagged as an expression of “post-Soviet youth” then this was an impressive riposte: he showed he had plenty more strings to his bow as he presented opening looks of relaxed tailoring, corduroy jackets and denim made in collaboration with Levi’s alongside genuine revivals of beloved Italian sportswear brands Fila, Kappa and Sergio Tacchini. “For me it’s very Italy and very Gosha,” said Rubchinskiy. These heartfelt collaborative garments may bear his logo in Russian, but the depth in this collection showed. As if to strengthen his point about collaboration, Rubchinskiy also presented a book published by IDEA and premiered a film made by the Russian independent director Renata Litvinova, entitled The Day of My Death (additionally, an exhibition of the same name was also taking place). A surreal neo-noir, the film's premise played out in the same factory where the show was held, starring Litvinova as a central protagonist orchestrating sexual encounters and exchanges, but with stylist Lotta Volkova and Rubchinskiy himself also making an appearance. Here in Florence, we got to see Rubchinskiy as designer, image-maker and zeitgeist catcher, growing beyond the boxed-in confines of his Russian roots. Gosha is ready for it all.

Raf Simons and Robert Mapplethorpe

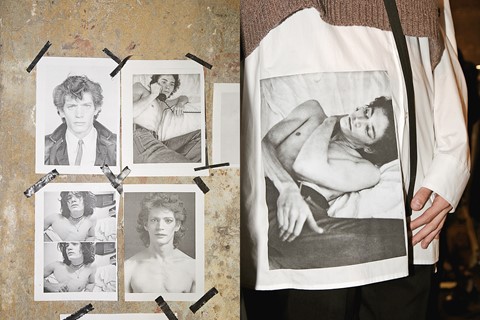

On the rooftop of the imposing Stazione Leopolda, a trio of Raf Simons mannequins (reportedly from his personal collection) were sat, peering down at us. They were just a teaser to the expanse that opened up at 8.30pm on the dot as a crowd of well over 1,000 people surged in, eager to lap up the countless figures on display in a throbbing redux of Simons’ 20-year-old body of work. The Sterling Ruby prints; the Peter Saville parkas; the Manic Street Preachers patches; the scrawlings of college graduation tees. They were all there, juxtaposed with female mannequin forms, gaffer-taped or customised with paint.

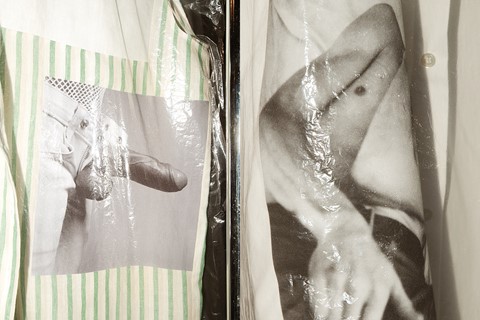

This would mark the fourth time Simons has shown at Pitti Uomo, and it was probably the most ambitious spectacle yet. With the audience scattered among abstracted Raf representations, and thus duly reminded of Simons’ significant contribution to the advancement of menswear, the scene was set for him to unveil his latest coup: a fully fleshed out S/S17 collection featuring Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs, created in collaboration with the Mapplethorpe Foundation. Simons was approached by the foundation to collaborate and so he began sifting through the artist and photographer’s archives, selecting not just his most famous portraits of Patti Smith and Debbie Harry and his more overtly sexual work, but also his still life photographs of flowers, to use in the collection. “I'm a fashion designer,” said Simons after the show. “So I thought the biggest challenge for me would be to not go and show Mapplethorpe’s work in a gallery but in relation to my own environment. I want to challenge myself also for the Foundation to hopefully make it believable to a different audience, not only people who are following art.”

It takes a designer with Simons’ understanding of a complex being like Mapplethorpe to be able to place his photographs on garments without it looking like a slap-dash art print. Simons has ample experience, of course, of positioning contemporary art within his own world. So here, beautifully printed photographs would be placed on the chest and hems of oversized shirts, on blankets slung on the shoulder like collectible keepsakes, and on apron skirts that would reveal flowers on one side and stretched underpants on the other. Mapplethorple’s famous subjects and erect penises would reveal themselves underneath slouchy sweaters and leather dungarees, while the photographer’s own sensual sense of style also came through in the skinny PVC trousers, thin neckties and leather bar-studded caps. This feverish fetishising of Mapplethorpe’s work was made complete with these stylistic touches. Whether on female mannequins, rakish models, or on many of the standing guests, Simons’ work has an enduring relevance that was demonstrated in full on this occasion in Florence. The Mapplethorpe collection has an instant-collectible quality to it that will certainly sell like hot cakes, but it’s yet another chapter in Simons’ impressive trajectory.