Since becoming the creative director of Comme des Garçons Parfums in 1993, Christian Astuguevieille has worked alongside the brand's president Adrian Joffe to produce the most artistically daring, wonderfully baffling and brilliantly cerebral single collection of scent art that has ever existed. Astuguevieille is well known for his miraculous ability to elicit masterpieces from the celebrated scent artists he commissions – think: Anne-Sophie Chapuis-Cariou and Martine Pallix’s rebarbative, seminal works of Industrialist art, Odeur 53 (1998) and Odeur 71 (2000) – and his work with lauded perfumer Emilie Coppermann is no exception. Most recently Astuguevieille commissioned Coppermann to conjure up a scent for Grace Coddington, in what would be the revered fashion editor's fragrance debut, but the duo had worked together twice previously, on iconic scents Serpentine and Floriental.

Serpentine was a 2014 collaboration between Comme des Garçons and the Serpentine Galleries in London’s Kensington Gardens. Under Astuguevieille’s creative direction, Coppermann created a scentwork of modern abstract minimalism – a sheet of scent with a texture like fine white nylon mesh that made absolutely no olfactory reference to any natural material at all. Serpentine is as eerie, soundless, and disorienting as a base jumper's flight through a massive white cloud.

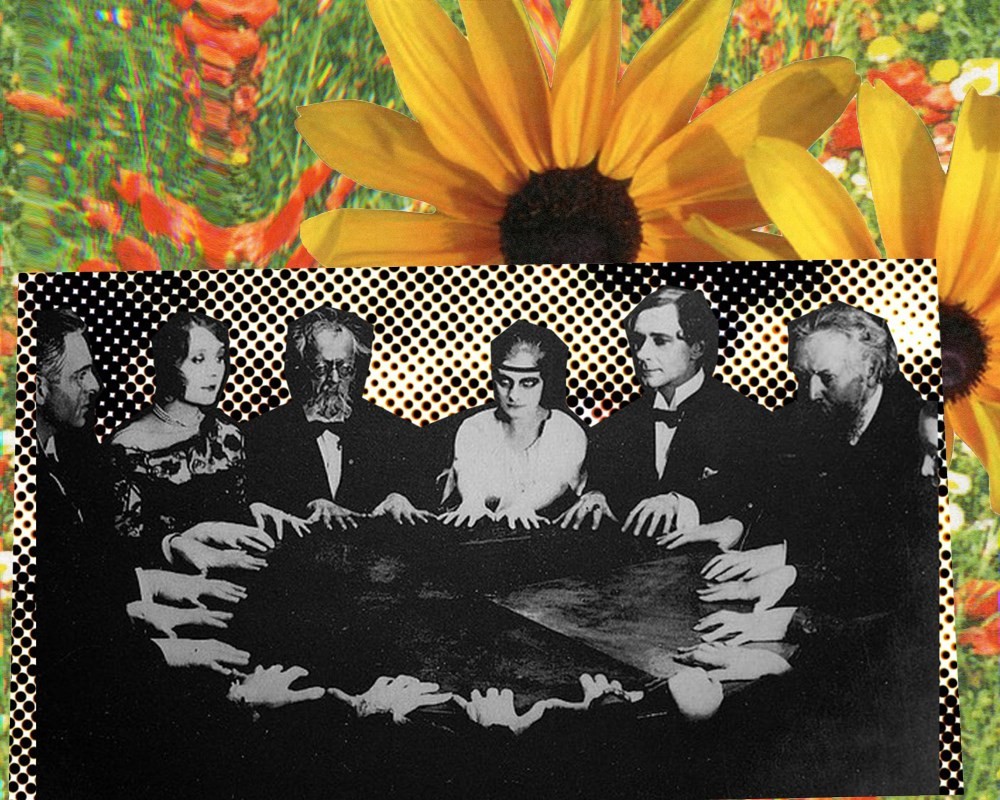

With Floriental (2015), by contrast, Coppermann created a work of contemporary Magic Realism, boasting Chagall-esque representations of spice and wood and flower: we recognise them and yet we experience them in distorted, fantastical form, their metaphorical colours impossibly vivid. Floriental’s heightened reality is hypnotic; experiencing the work is like attending a séance.

When Comme des Garçons decided to collaborate with Coddington on her eponymous fragrance, Astuguevieille began the process by "talking with Grace." Coddington for her part was a patron who found the work she was commissioning "difficult to articulate". "I don’t speak perfume," she said of the process. "I’m visual." She was, however, sure of two things: that she "certainly didn’t want something clinging", and that the starting point should be roses. "[For the rest of the conversation] I fundamentally talked to Christian about myself," she divulged. "It really is me in a bottle."

Coppermann by no means had an inside track on the commission. "I begin a project by bringing the concept for the work to various perfumers," Astuguevieille explains, speaking of the much-envied group of artists with whom he frequently collaborates – including Bertrand Duchaufour, Nathalie Feisthauer, Antoine Maisondieu, and Nicholas Sieuzac." The perfumers I work with have a sense of my écriture," he says. "I don’t like excessive beauty, and they know it. They’ll say ‘This one is far too beautiful for Christian.’" In the case of Grace, Astuguevieille approached seven such perfumers, of whom Copperman was one. "I spoke to the seven of them about Grace’s rose, a natural rose, and asked each to make me some initial sketches," he says.

Coppermann is highly complimentary of Astuguevieille's creative process, describing him as an "excellent intermediary" between patron and artist – "he beautifully communicates concepts I need to translate into olfactory form" – but in this case, she found the concept he brought her somewhat bemusing. "A ‘natural rose’ is at once very specific and very undefined," she explains. "One can interpret a rose in an infinite number of ways."

Astuguevieille "wasn’t directive", simply leaving the task in Coppermann's capable hands. She sent him five sketches, including several traditional roses – varying takes on "the ‘big rose’ [where] you put in a bit of peony, a bit of fruit, some patchouli, the codes you know will reassure" – and one more unusual one. "The sketch I sent him that I myself found most interesting was a small, scrappy, wild rose that grows in the rocks among the weeds and wild herbs where the seeds are blown. They are not sewn, not cultivated; they grow unattended, competing with vines and grass."

It was extraordinarily basic: "I built it with a Moroccan rose absolute with an Egyptian basil essence and a mint essence to play the role of the scattering of green herbs, the wild grass. The effect is of something not maîtrisé, not cared for. In fact, it was as much a sketch of what was around the rose."

Astuguevieille received a total of 35 initial sketches from his seven chosen artists – a number that left him, surprisingly, undaunted. ("I don’t like to close anything off," he discloses, "particularly at the beginning, because it can close off a potential route.") After painstaking examination, he narrowed down the submissions to a select few – all of which he describes as touching on "the green concept" in some way – and took them to show to Coddington. Coppermann’s, he says, spoke to Coddington immediately. "There was another sketch that was excellent," says Astuguevieille. "But Emilie won – though only by a hair. The sketch Grace chose was a rose that was not cultivated, that had mint growing next to it, grasses, weeds."

Winner decided, it was up to Coppermann to develop the final scentwork – but not before another challenging direction from Astuguevieille. "When Christian and I spoke after Grace chose my first sketch, one of the few things he said to me was, 'Do it more as a rose bud,'" she explains. "And I thought: A rose bud... So we’re really not at all in the floral. A bud is a clarity of image but not, strictly speaking, an olfactory rose."

Nevertheless, she set about sketching out her next modification, and soon two became five became 20 became 50. "It’s a continual work. From each mod [draft], I made around 100 different variations. I chose a few directions I liked, then twisted them." She gave Astuguevieille five more, he choose two and presented them to Coddington. She chose one.

For Astuguevieille, Coddington’s method was subtractive. "Grace said no. That was the way she guided me. ‘Not that’ and ‘not that’ and ‘NO!’ but sometimes ‘maybe this’. It’s actually quite helpful; one can be guided by that. I brought her roses inflected with peonies, roses with spices, roses that were extreme – she could have chosen any of them. She didn’t. She kept moving toward Emilie’s wild nature."

Coppermann’s job was to keep on evolving. "I wanted it to fizz, to impact, to breathe. I added rose oxide and pink peppercorn. I chose Magnolan [a scent molecule made by Symrise, Coppermann’s scent company, which has it under patent] because the material brings volume to the perfume as a whole, but also because rose oxide is a carbonated burst that opens the work, and Magnolan anchors that rose explosion in the heart of the natural rose." She also put in a small amount of cardamom to add power in an unusual form. "Cardamom is slightly citrus," she says. "I added the molecule Amarocit to give a freshness that is slightly grapefruit with a lovely bitterness."

When Astuguevieille came back the next time he remarked, "Tenderness," and, "Intimacy" – although Coppermann notes that he was never directive about materials, something she greatly appreciates. Nor, she says, does he communicate with images. "I have clients who will state ‘We want a glass wall,’ but Christian rarely uses metaphors. He knows exactly what he wants. He wants my imagination." So how did he guide her? She hesitates. "He’s very reserved in his words and at the same time very strong in his personality. It’s another way to communicate."

Unlike Astuguevieille's previous directions, for Coppermann "Tenderness" and "Intimacy" were very specific; the solution was obvious. "Grace wanted a work that was for herself. So I began to create an envelope for the herbs and the rose." So Coppermann set to building the envelope using Globalide, a Symrise molecule that smells like clean skin warmed in the sun. ("I intentionally built it without shadows," she expands.) She then layered in Ambroxide, a molecule that gives warmth and is never dark, before weaving in complexity – Cashmeran, Galaxolide, Ambrettolide to be exact. But although these verbose ingredients sound deliciously seductive, the envelope, Coppermann clarifies sternly, is "not sexy – not at all. Sensual. I drowned the rose in this envelope."

On the last and sixth creative iteration – hundreds of mods of which she gave two or three to Astuguevieille – Coppermann went back to the very beginning again: the heart of the work. She decided to add a natural vetiver, a wild tropical grass from Madagascar – "we [Symrise] have fields and fields in Madagascar where farmers give us wonderful cinnamon, ginger, vanilla, vetiver" – and loved the effect. "This particular vetiver gives a very citrus/bitter/grapefruit-esque vetiver that is delicious, not earthy." She also tried adding a few molecular special effects – vetiveryl acetate and vetiverole – but in the end stuck to the natural vetiver for the final, Coddington-approved scent. "It gave the work so much more lift and complexity. This wonderful texture," she reflects smiling: "Slightly wild."