AnOther traces the history of male icons who have challenged modern tropes of masculinity, from Louis XIV to Andreas Kronthaler

It's important to note that it's only within the past few of centuries of western fashion that menswear has become synonymous with the tropes of masculine dress we might think of today. Even this relatively recent history of gender-regulated, pared-down, ostentation-eschewing style has been punctured with numerous anomalies that challenge the norms of said masculine taste standards. Heels, cosmetics, and other accoutrements that often constitute the cultural symbols of femininity have, at various periods, been equally associated with men and masculine ideals. As critics today return to embracing these often-neglected facets of men’s style, and designers from Andreas Kronthaler for Vivienne Westwood to Grace Wales Bonner turn away from contemporary conventions of masculinity, we explore the appearance of the decorated male throughout history.

Power Heels, Powder and Patriarchy

As is so often the case, one cannot speak about western fashion without mentioning examples outside the Occident. Makeup for men is known to have been prominent throughout the ancient world, with nail varnish being worn by those throughout all ranks of society at least as early as 3000 BCE in Japan and China. Perhaps the best-known example of ancient male cosmetics would be the wearing of eye makeup by the ancient Egyptians, while heels are a comparatively younger affair, worn by men throughout the medieval near east where they had the functional purpose of allowing horse riders to stand up in their stirrups and fire arrows. When these same Persian heels arrived in the court of Louis XIV, their purpose was altogether more decorative. Himself an admirer of this elevated footwear, they came to be known as the “Louis Heel”. The image of the 17th aristocrat is possibly one of the most prominent historical images of the decorated man; alongside heels, they opted for wigs, face powders and other makeup such as artificial beauty spots.

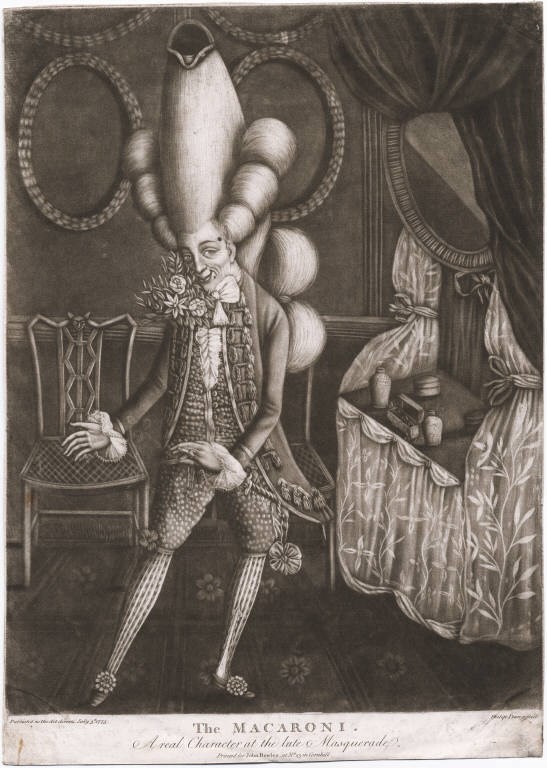

So many of these items were simply not yet strict symbols of femininity. Indeed, far removed from today’s concepts of masculine dress, many of these were as much to do with power and patriarchy as individual expressions of style. It is often cited that the diminutive King Louis took to heels and towering wigs to impart a more “monarchic” height, while it has been observed that it was only due to trends of women imitating men’s fashion that the heel became common amongst both genders. In 18th-century Europe, particularly in England, decoration reached new heights with the “Macaroni”. Macaroni referred to groups of cultured young men whose interest in fashion was seen as excessive. Their hairstyles and powdered wigs, jewellery, attire, makeup and generally “effete” appearance were cause for concern amongst many who felt they were rather too unmanly. It is worth noting, however, that whilst frowned upon and associated with effeminacy, there was not quite the same negative weight to such styles (or indeed to effeminacy) as there later was in Victorian society. Class, however, was heavily at play and while it might be considered acceptable or even suitable for a man of certain social status to sport highly stylised attire, a man of lower rank would not be received as warmly.

Eccentrics and Exiles

There was a notable shift come the Victorian era, one that was particularly visible in Britain. Following some high-profile scandals in the press, attitudes towards gender became markedly less tolerant. In many ways, the late 1800s in particular can be thought of as a cut-off point for the social rules that shaped men’s style – whatever was considered masculine around this period remained so in a manner that had not quite been so rigid previously. This rigidity did not mean that there weren’t several who defied or ignored convention. If fortunate they were classified as eccentrics, as was the case with Henry Cyril Paget, whose elaborate headdresses and bejewelled costumes (which often contained Louis heels), amazed and also horrified many.

Paget, however, had the protections of wealth and status and that often worked to convert perceived queerness into tolerated eccentricity. Others were not so lucky. Even the likes of photographer Cecil Beaton, who was by no means lacking in money and social standing, suffered from the rampant homophobia that suffused the post-Victorian air. At a friend's ball, he was famously dunked in a fountain by a group of “hearties”, because of his wearing makeup. Similarly, Quentin Crisp’s love of makeup and feminine attire resulted in his being chased through the streets, kicked and beaten. What was certainly apparent by the 1930s was that, in the public consciousness, the image of the decorated man had become consolidated with a vision of femininity and queerness that was violently received.

The Opening and Breaking of Menswear

This consolidation was to have a lasting effect. Vogue ball culture, which emerged from American black drag scenes of the 1930s, is particularly pivotal, in that it shows how queer cultures and groups utilised the negative connotations of the decorative to challenge and undermine the dominant status of masculinity. Elsewhere, counterculture made constant recourse to what had become strictly feminine symbols. With the disco movement, we see men in heels once again, this time in the form of platforms, while the flamboyant impulse was once more loose in the embracing of all the glitter and ornament that have now come to be thought of as “camp”. Similarly, the New Romantic movement which came about almost a decade later is defined by its disregard of the doggedly concrete rules about what men could and couldn’t wear, elevating instead the “excesses” of costume.

Current conversation regarding menswear and cosmetics is becoming increasingly preoccupied with noting the breaking down and opening up of menswear. For many, the mere loosening of men’s fashion is not enough – the very existence of menswear and womenswear as two separate strands, something which is central to the mechanisms of the fashion industry, continues to keep harmful gender norms alive (in spite of the move of some designers, like Andreas Kronthaler for Vivienne Westwood, to do away with such divisions). While designers like Claire Barrow emphasise the essential non-binary nature of their clothes, when it comes to more commercial bodies, such as Selfridges, who recently made the decision to promote gender-neutral clothing with a retail concept space titled 'Agender', it can be hard not to suspect the cold machinations of trends and advertising at work. For some, defying dominant gender standards is a choice, but for others, it is a necessity and not something to be left to the mercy of consumerism.