As British summer crescendoes into a heatwave, we reflect on the 60s designer whose ethereal, form-hugging creations were the perfect fit for the season

“What’s wrong with the way women dress is that they don’t know anything about their bodies,” Ossie Clark boldly stated in 1971, referring to the 60s’ prevailing plastic-coated, thigh-grazing look that favoured whippet-thin boyish physiques. In his own words, Clark designed clothes for women who wanted to look like whores – because “whores know everything about their bodies, and that’s why they look so good.” Such was the confident charisma of Ossie Clark, the designer who became known as the ‘King of Kings Road’ for his supremely cut yoked, bib-fronted 30s-and-40s-flavoured dresses that dipped at the back and peaked at the shoulders, all the while revealing the décolleté and flowing with sensual movement and sometime-transparency. Clark defined the spirit of London during the period between Mary Quant’s go-go mini-skirt and Malcolm Maclaren and Vivienne Westwood’s subversive punk movement, from 1965 to 1974.

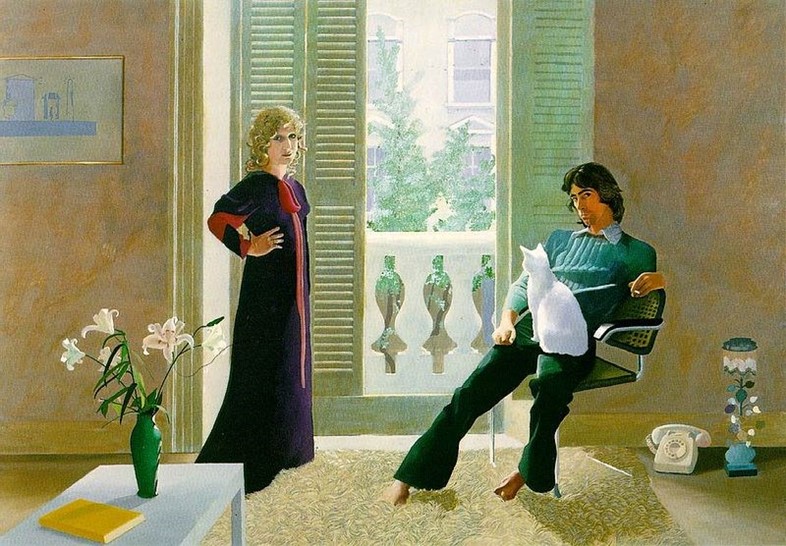

Clark, and his wife Celia Birtwell (or Mr and Mrs Clark as per the David Hockney portrait hanging in Tate Britain), came to define the bohemian quarter of west London that was home to a generation of bright young things, presided over by Candida Lycett Green (née Betjeman), who famously said, “In a Bill Gibb, I feel like an Odeon cinema, but in Ossie Clark, the reaction from men was just unbelievable”. Celia designed the prints for the wispy crepes, silks and chiffons and Ossie would magic them into beautiful clothing with a slight Blitz sensibility. Having both grown up in the north of England and met at college in Manchester, they were demonstrative of a new dawn of social meritocracy and modern London-centric lifestyles. When Hockney painted the couple in their Notting Hill home, the result was a snapshot of modern, barefoot living set against neutrally plain walls – the plastic telephone casually placed on the uncarpeted floor, the single tubular chair and tablecloth-less sharp-edged coffee table reminders of modernity in a townhouse that would have once been heavily decorated. This is the world that Clark and Birtwell occupied and represented, and Clark's designs epitomised this brave new way of living.

The Show

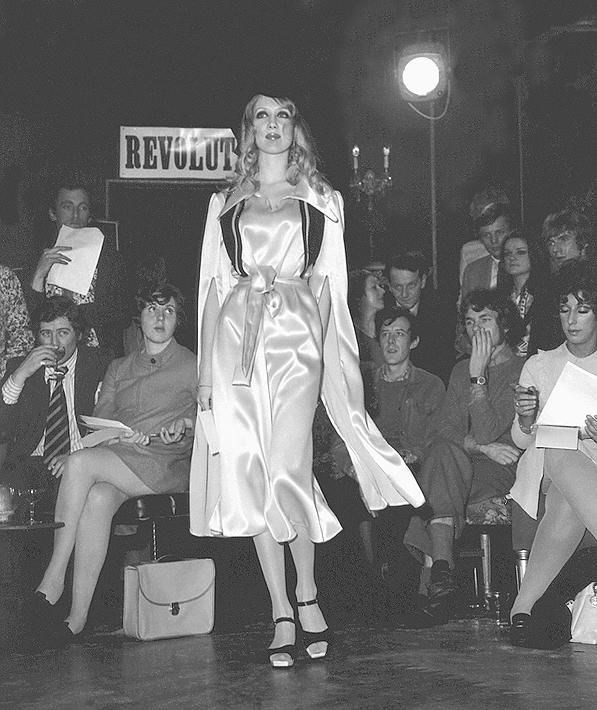

Ossie Clark’s fashion shows were legendary, often veering towards theatrical events in venues as grand as the Royal Albert Hall, Royal Court Theatre or the more offbeat Dingwalls in Camden Town. In 1970, he staged a show at Chelsea Town Hall that attracted hordes of people banging at the door. The room was filled with celebrities, with a distinct lack of fashion press or buyers (Clark severely lacked business acumen). The soundtracks were compiled by Pink Floyd’s David Gilmour and the audience included everyone from Cecil Beaton to Lady Diana Cooper and Christopher Gibbs, as well as members of the ‘Chelsea Set’: artists David Hockney and Patrick Procktor, the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, Brigitte Bardot, Marianne Faithfull, Liza Minnelli, Jeanne Moreau and Britt Ekland. It was, said Vogue, “more of a spring dance than a show.”

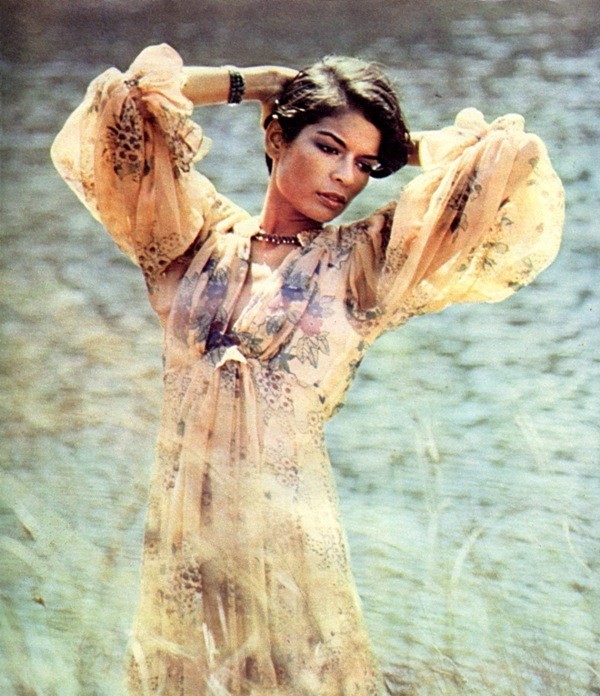

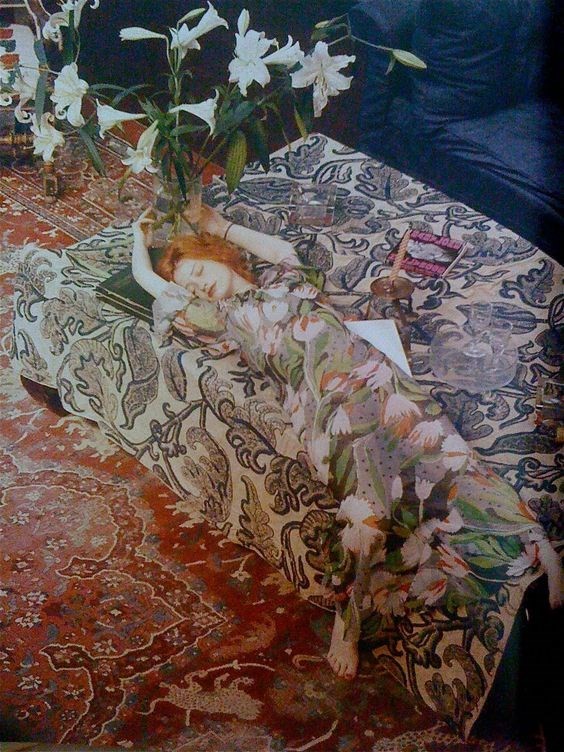

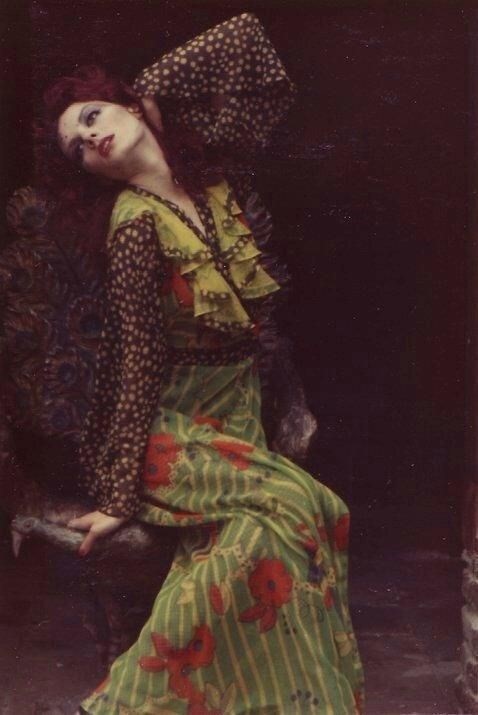

The models danced rather than walked, and most of them were as high as kites, flashing incendiary splits from side to side and waving their arms in typical spaced-out style. “Being backstage at one of Clark’s shows was like being at the best party in London with all the most beautiful people,” said Hockney in Jack Hazan’s 1974 documentary A Bigger Splash. Patti Boyd, Kellie, Carina Fitzalan-Howard, Amanda Lear, Gala Mitchell, Kari-Ann Moller, Veruschka and Bianca Jagger all modelled. These were women that were now entering their late 20s or 30s and, for some, having children and embracing their maturing bodies. They had just emerged from the ‘youthquake’ as Diana Vreeland called it, which characterised by teenage bright-eyed innocence and appropriations of doll-like Victorian childrenswear. Clarks’ dresses were sexy, womanly and exquisitely cut, thanks to his technical skills – he was known to be able to cut straight into fabric without even consulting a paper pattern. “They were very fitted, with little shoulder pads for a little lift,” recalls Willie Walters, who was a fashion student at St Martins at the time. “They were so slinky you weren’t supposed to wear underwear with them. No pants, so that you could just have sex on a car bonnet or something. That was the thought!” Each one had a secret pocket that would just about fit a key and a £5 note – Clark’s idea of all that a liberated woman needs.

The People

Anyone who was anyone had an ‘Ossie’ – even Marianne Faithfull and Anita Pallenberg had to share a single snakeskin suit between them, which Faithfull wore to her several court appearances. Clark produced two collections a season – a high-end one for Quorum, Alice Pollock’s King’s Road boutique, and a lower-priced one for a licensing deal with Radley. Ossie’s main and most important collaborator was his wife, Celia. Working independently, she would design the fabrics at home and drop them at his studio before disappearing. Without Birtwell’s prints, Clark’s designs would merely be plain crepe and silk and hardly have the same visual punch – Birtwell drew on Art Deco forms, Audubon botanical sketches and sometimes kitsch table-cloth equivalents in off-beat colours such as prune, dead-rose, saffron, myriad blues. Clark was obsessed with historical dress, citing Madeleine Vionnet, Lucien Lelong and Charles James as his favourites. He would often source vintage garments from nearby Portobello Market that he would then dissect to discover the secrets of their construction.

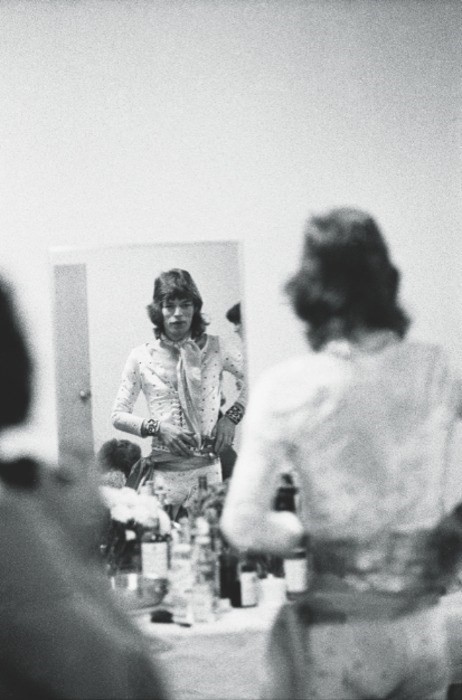

Ossie also designed stage costumes for Mick Jagger, crafted from lycra so that they could be put in the washing machine straight after the show. In 1969, he accompanied the Rolling Stones across America for their Sympathy for the Devil tour, by which point he had become known for his hedonistic lifestyle. “Ossie had the glamour and the sheen of the rock stars of the era,” remembers photographer Tim Street-Porter. “In terms of his talent, Ossie could easily have been as great as they were, but the thing that let him down was his personality,” says Judith Watt, the fashion historian who wrote the seminal book on Clark that accompanied the V&A’s 2003 retrospective on the designer. “Ossie was a live wire: volatile, endearing, acerbic, difficult, brilliance packed into a small frame dressed in his mother’s hand-knitted jumpers and a Celia print shirt or pistachio-green Tommy Nutter suit,” continues Watt. “He loved nature: trees, flowers, the moon, stars, colour, natural form; all excited him and his aim was to create beauty in his work, not to make enormous amounts of money, as is so often the yardstick by which a successful designer is measured today… He was a Gemini and a fragile soul and if you look at the people who really survived the 1960s – people such as Mick Jagger – they were tough as old boots. Ossie was not tough and the drugs and the drink got to him. And, later, he never had the kind of support or commercial infrastructure he needed for his career to succeed.”

The Impact

Despite his short-lived career, Ossie Clark is widely remembered as an innovator whose talent and vision transcended the microcosm of the King’s Road, and influenced countless designers, most notably Yves Saint Laurent and countless New York designers. Saint Laurent idolised Clark aficionados Loulou de la Falaise and Talitha Getty, and it was Getty who first introduced him to Clark at her and John Paul Getty Jnr’s ‘pleasure palace’ in Marrakesh. The influence of Clark upon Saint Laurent can be seen in the latter's scandalous 1971 fashion show, which would hardly have shocked across the channel by that point. Clark ushered in a new era of womanliness and grown-up sensuality, with an emphasis on the female body – Mae West was one of his pin-ups, and he religiously kept diaries inspired by her dictum, ‘Keep a diary and one day it will keep you’. Clark’s greatest skill, however, was his freehand scissorwork and ability to cut into fabric with masterful ease. It allowed him to create garments that had a unique structure that was inherently flattering, from his famous snakeskin motorcycle jackets to his slinky tailoring.

He made money in the 60s ("Like everyone else", he said later, "I blew it"). In the 80s, he went bankrupt and by 1992, although his clients had included the most fabulous, most beautiful, richest women of their day, he was living in a council flat in Notting Hill, signing on when commissions failed to materialise. As journalist Georgina Howell reported in 1987, he was living in squalor with a Buddhist shrine composed of Sobranie cigarette packets and roses stolen from nearby Holland Park. Ossie came to a tragic end when he was murdered by his young lover in 1996. His disregard for members of the fashion industry, instead preferring to court his friends and celebrities, meant that his legacy would be difficult to preserve and few examples of his work entered museum collections. Clark’s focus was on making beautiful clothes, not trying to ensure posterity and perhaps that’s what marks his significance. Such an artisanal, small-scale work of a technical genius is passed down through oral history and the treasured clothes held in private wardrobes – a sentiment that becomes especially pertinent as a countercurrent to the rise of gargantuan brands, with their slick operations and huge advertising budgets, which are celebrated as the leaders of fashion today.