Rebecca May Johnson reports on Ukraine’s biannual fashion event – a burgeoning initiative that puts emerging Eastern European talents on a global stage

A critical-creative culture that encourages aesthetic risk-taking alongside a rigorous design process is essential to developing a robust fashion week schedule. Even commercial, wearable collections must say something new each season. At Daria Shapovalova’s Mercedes-Benz Kiev Fashion Days, a rival event to the Ukrainian Fashion Week held in October, the moments of brilliance arrived through innovative reworking of Vyshyvankas, traditional Ukrainian costume hand-embroidered with cross-stitch – a symptom of a reinvigorated national identity in the wake of the Euromaidan revolutions of 2013-2014 – environmental politics, and distinctive silhouettes and fabric development. On the flipside, the over-literal influence of fêted eastern European peers Demna Gvasalia’s Vêtements and Gosha Rubchinskiy, as well as Hedi Slimane’s Saint Laurent, J. W. Anderson and Marques'Almeida’s disheveled denim, was a recurring issue, as were poor fits, fabrics, and underdeveloped ideas. This, however, made those with a unique creative outlook view all the more prominent...

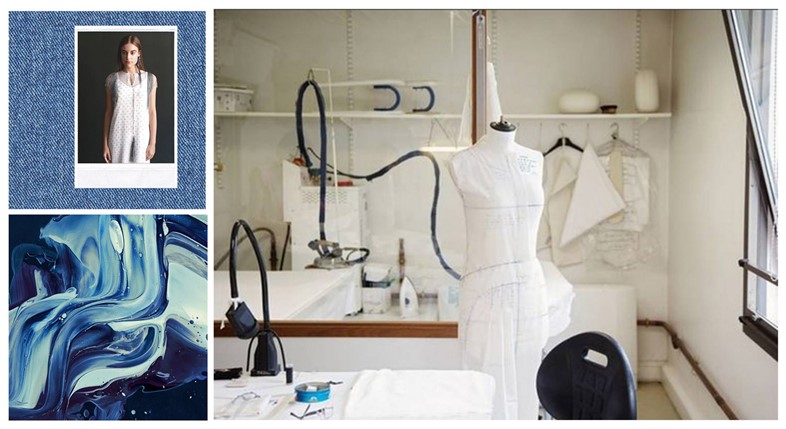

Rcr Khomenko by Yasia Khomenko

Some of the other designers at Kiev Fashion Days could learn a thing or two from the way that Yasia Khomenko put together her show. After the somewhat bland sheen of the main venue, a vast, controversial building constructed so that escaped former president Viktor Yanukovych, now hiding in Russia, would have a helipad in the town centre, Khomenko’s venue, a disused Soviet shopping mall, was a breath of fresh air. The designer, who visited London in February as part of Ukrainian Fashion Week’s ‘Fashion School Rebels’ showcase, worked with long-time collaborators Forma, a group of architects and urban planners, to produce the show. Upcycling has been a focus of Khomenko’s collections since the beginning, and she is a passionate advocate of using only thrifted and recycled fabrics, dreaming of “a mass market of second hand”. Here, Khomenko took her commitment to an ecologically sound future one step further, founding a fictitious cult dubbed the ‘Church of Upcycling’.

Walking past white coated ‘cult members’ who were guarding the door, we made our way through the mall, where the only sign of the site’s former life is a single security guard watching over one remaining shop of glitzy, 1990s style clothing. Just as Khomenko gives old fabric a new context through her clothes, Forma’s show production suggested that the sense of proportion and use of sturdy, beautiful materials of such architectural Soviet relics, have a future yet. Multi-coloured light streamed through patterned glass panes on the stairwell onto beautiful polished stone walls, while in the main space, soft pink marble or sculpturally ridged surfaces soared up and up, lit by sunlight through floor-to-ceiling windows.

For a performance before the runway show, Khomenko ‘upcycled’ old friends into performer-models who stood in the shape of a church structure, and every few seconds, one broke away, orbiting the group and then re-joining it. The runway – well, a lap around the shopping mall – featured Vogue Ukraine’s first editor-in-chief Masha Ysukanova, who opened and closed the show. Shirt-dresses were the main order of the day, with different fabrics, mostly office-worker stripes of different colours cut across each other to form contrasting silhouettes – shift dresses, button-downs, bralettes, shirtsleeves tied round as belts, rather like those seen at New York-based brand Monse. But Khomenko’s cult had its own symbolic language too, which riffed off the classic recycling iconography of arrows, printed onto clothes and pointing in all directions, suggesting many directions of travel.

The final look, made from an African wax-print fabric featuring the Virgin Mary, was printed a gold explosion overlaid with an infinity recycling loop where Mary’s head would be, displacing the Christian icon for an ecological version – an interesting development of Khomenko’s theme. She has had success producing fun, wearable collections with original, playful prints for several seasons now, and it would be exciting to see her work the fabrics harder to see what else she can find.

Litkovskaya

Lilia Litkovskaya, who also showed off-site in a Brutalist-style multi-storey carpark, set herself the challenge of synthesising two diametrically opposed aesthetic influences this season – the abstract work of mid-twentieth century Italian artist and sculptor Lucio Fontana, and the notoriously decadent 18th-century queen of France, Marie Antoinette. In particular, Litkovskaya worked with imagery from Fontana’s Tagli (cuts) series, where canvases are punctured and slit in straight lines to blur the distinction between two and three dimensionality. However, Litkovskaya found a convincing link: cuts into Fontana’s canvas, often said to refer to pain, wounds and female genitalia became part of a narrative that referred to Antoinette’s execution at the guillotine, with flashes of blood red in wet-look leather sharply puncturing a palette that otherwise stuck to white, gold, black and brown. Antoinette’s decadence and era showed themselves in an 18th-century style bomber jacket with concertina shoulder joins in rich, gold silk and modernist readings of ruff-necked white shirts and men’s frock coats in pinstriped wool. Lucio Fontana’s work translated well through the colour palette, and the productive disruption of silhouettes through cuts and slashes – only occasionally going too far, as in the case of a few pairs of trousers with only one leg. The complexity of Litkovskaya’s work and the quality of the fabrics that she uses are, so far, the best I have seen in Kiev during my two visits.

Ksenia Schnaider

Ksenia Schnaider’s distinctive denim silhouette – one that she’s been developing through several seasons – is baggy at the thigh, slashed at the knee and tight on the calf, rather like grungy chambray knickerbockers, and worked well with fun printed pieces that employed Ukrainian imagery such as cherries, red flowers and the balloon sleeves, necklines and fabrics derived from Vyshyvanka national costume. The husband and wife-team’s creative chemistry, with Ksenia overseeing the whole collection and Anton doing prints, produced confident and convincing work, though still only a few years old, and certainly set the foundations of a strong denim brand.

Bekh

While a number of Masha Bekh’s pieces were more than a little reminiscent of Marques'Almeida’s denim, she had greater success with designs that played on the traditional cross-stitching of Ukrainian Vyshyvankas: “I want to rework Ukrainian tradition in my collections,” she commented. Bekh, who trained at Instituto Marangoni in Milan, London and Paris, used ‘sketch’ embroidery that left trails of loose threads from fabric like tassels in her modern rendering of traditional craft, with the semi-finished appearance of the embroidery revealing the trace of the artisan. This was particularly well articulated in a pair of sheer trousers embroidered with Ukrainian cross-stitch, in oversized houndstooth, laid over a net-curtain flower print, as part of a suit that had raw hems.