Photographer Chris Steele-Perkins presents his extended study of the Teds, the working class style subculture who Brylcreemed gender norms into stunned submission

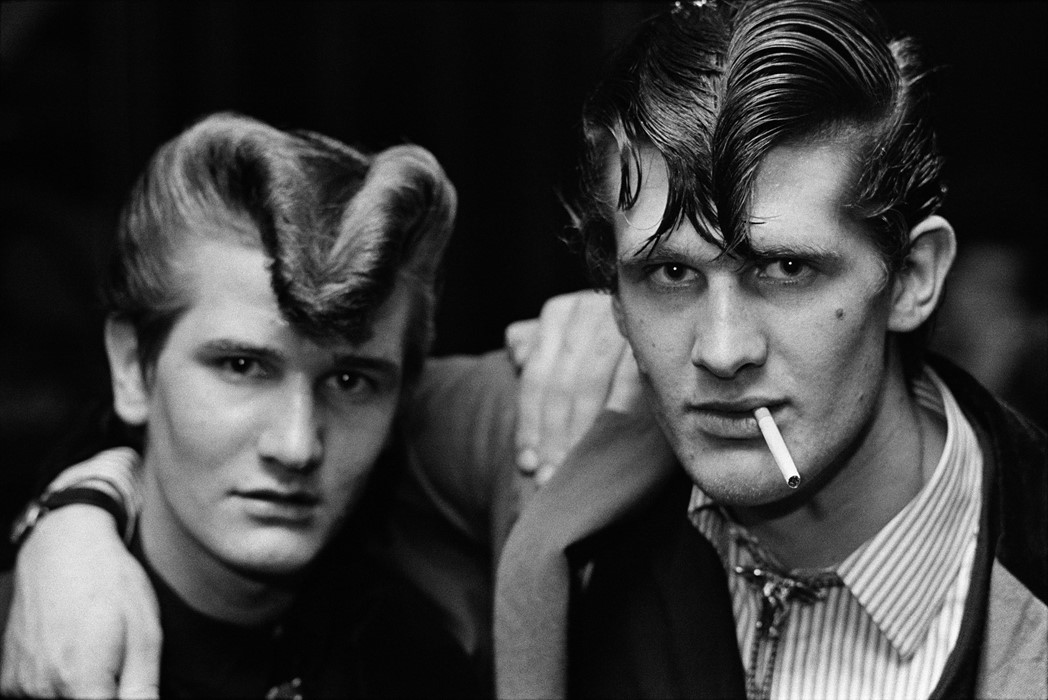

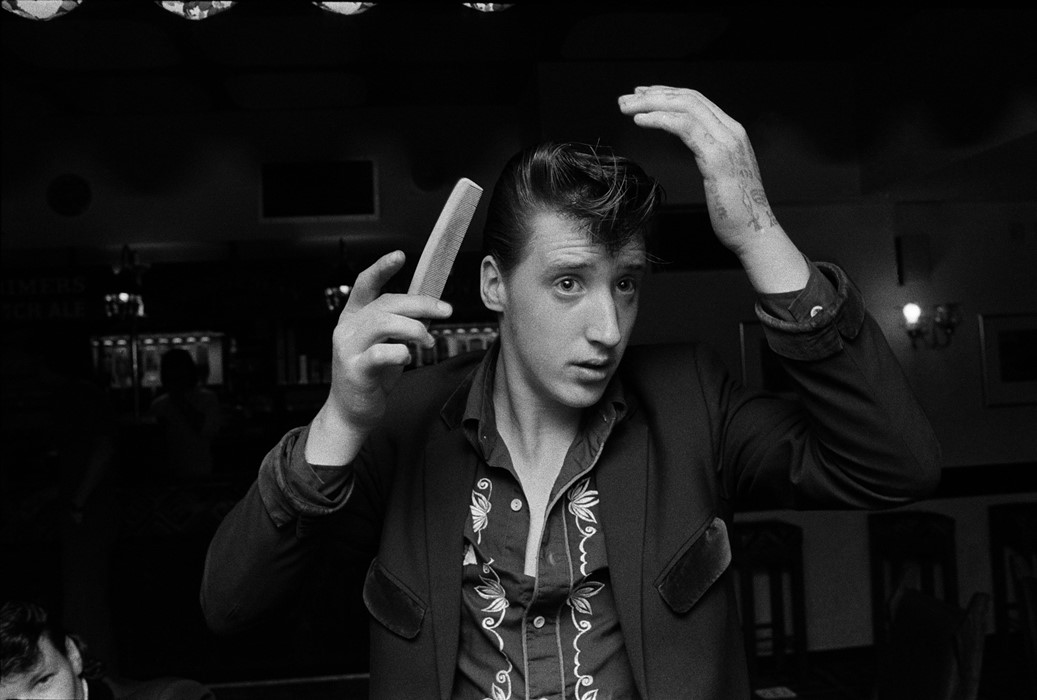

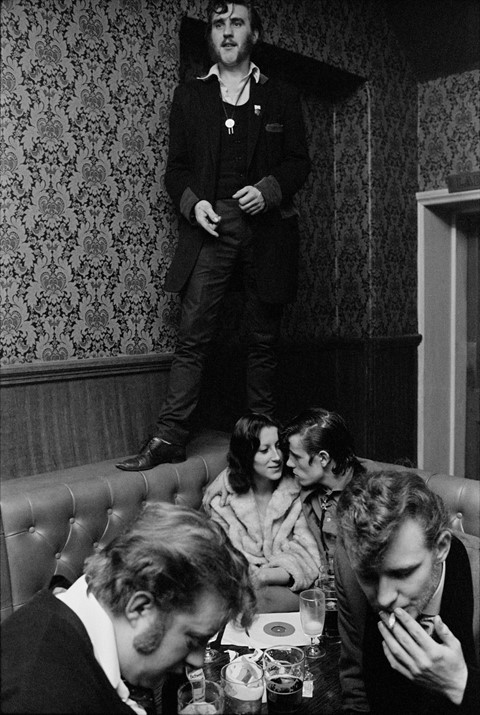

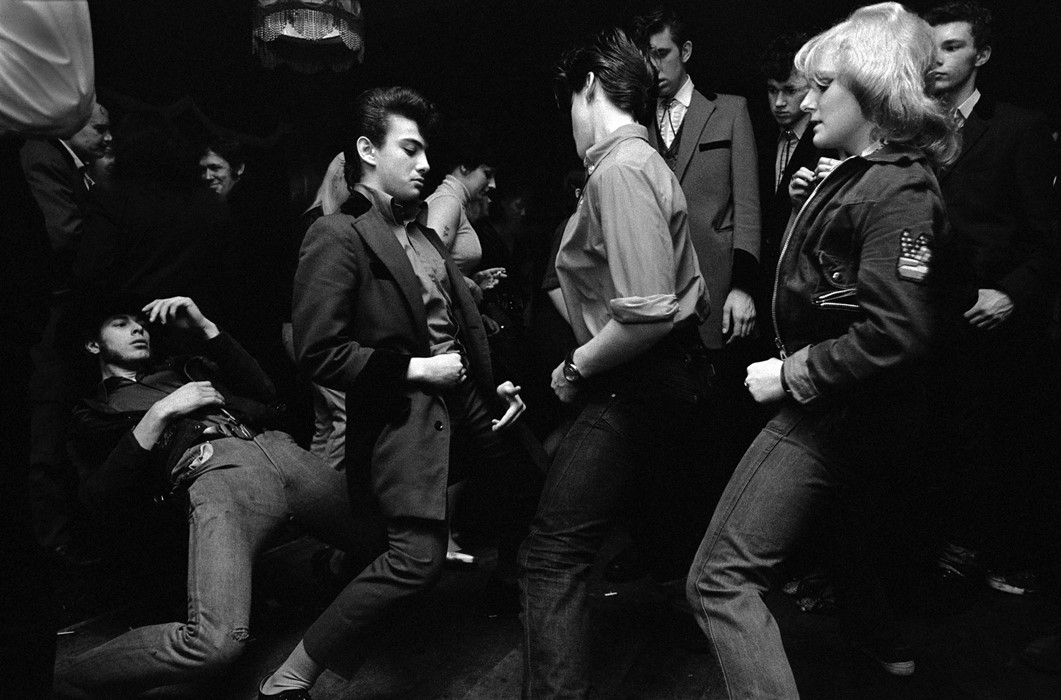

With the post-war economic prosperity which swept Britain in the 1950s came a slew of unprecedentedly flamboyant fashions – not least among them the Teddy Boys. Characterised by a ‘Drape’ – a long, velvet-lapelled and -cuffed overcoat – and an extravagantly ruffed collar fastened with a shoelace tie, these were working class men with a disposable income, however small, who were fixed on establishing themselves as part of a style tribe. They were tough, elaborately coiffed and impeccably turned out, presenting an as-yet-unseen new configuration of masculinity. (Teddy Girls, though in the minority, embraced similar codes.) They commanded confrontation, and they weren’t afraid to receive it.

Magnum photographer Chris Steele-Perkins’ first encounter with the Teds came about when he was a ten-year-old boy living in the suburban town of Burnham-on-Sea in Somerset, looking up warily at mean-faced teenagers in pseudo-Edwardian dress on street corners. “My father used to threaten to turn me over to them if I didn’t behave,” he laughs. It wasn’t until he was working as a freelance photographer some 20 years later in the 1970s, when the Teds revival was already in full-force, that the potential for an extended photographic project documenting the style subculture really came into fruition.

Together with a writer friend, Richard Smith, he set about documenting gangs of Teds up and down the country. Starting out in the Adam and Eve pub in Hackney, the pair soon expanded their search countrywide, travelling to places like Nottingham, Newcastle and Bradford to conduct an extended investigation which was entirely self-funded. One bank holiday weekend in Southend-on-Sea, where Steele-Perkins had followed a gang of Teds with a view to capturing their peculiarly British tradition of spending long weekends at the seaside causing trouble and starting fights, the photographer had the idea of standing his subjects up against a wall, thereby transforming reportage photography into portraiture.

"These were working class kids who were going to be butchers and bakers and so on, and they wanted to be taken more seriously" – Chris Steele-Perkins

What results, all in all, is a grainy monochrome study of a style subculture – a tribe of boys on the cusp of becoming men who weren’t afraid to carve out their own space in the world – and, when he searched out former subjects to take follow-up photographs 30 years later, Steele-Perkins discovered that many of his subjects remained devoted to the codes of their cause. “It was fascinating to me that this had meant so much to them,” Steele-Perkins explains. “They had assumed an identity through it, which was, I guess, the purpose from the very beginning. These were working class kids who were going to be butchers and bakers and so on, and they wanted to be taken more seriously. They wanted people to pay attention to them – kids have always wanted that.”

What’s especially fascinating about the Teds, he continues, is that their styling came from such frugal foundations (as is the case with their neighbouring subcultures, like skinheads and mods). “It was very much a magpie thing,” he says. “It came from austerity, it came from charity shops. The skinheads, for example, their tight trousers, and the jeans that were halfway up their legs, that was all because they couldn’t afford a new pair of jeans, and so they were still stuffing themselves into an old pair. They would blend that with what they could find from America, what they could see in the newspapers and magazines.” In this, he concludes, the Teds were pioneers. “It’s what the Teds did first. They were sampled by later generations who were looking back to see what had come before.” And as Steele-Perkins' resulting book, The Teds, ensures, they will be able to for many years to come.

The Teds, by Chris Steele-Perkins with text by Richard Smith, is out now, published by Dewi Lewis Publishing. The series is also on display in an exhibition at Magnum Print Room until October 28, 2016.