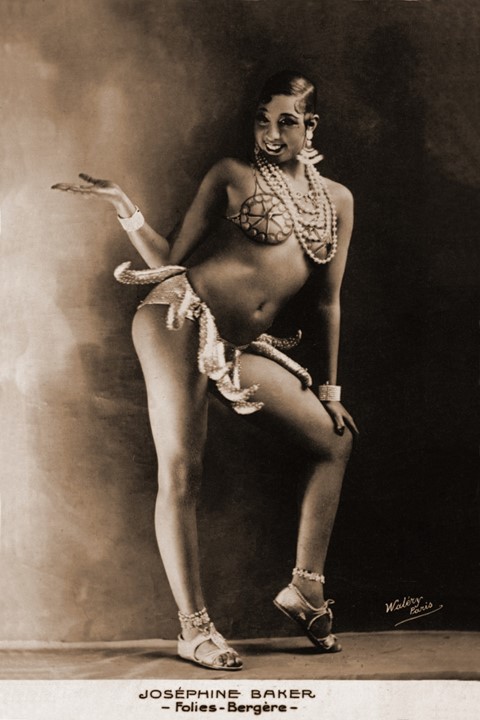

The magnetic Josephine Baker never ceased to rally against racial discrimination and gender inequality – albeit in her own, fabulous way

If you happened to find yourself gallivanting around Aquitaine in the south of France in the late 1940s, there is every possibility you might have stumbled across the Château des Milandes. A Renaissance manor, all turrets and gargoyles, it was architecturally and historically of note – not to mention its more modern additions: a swimming pool shaped like the letter J, an experimental farm, and waxwork figures depicting strange scenes from the 1920s. It belonged, of course, to none other than Josephine Baker, the St Louis-born expat turned dancer, singer and actress whose influence was to resonate throughout the 20th century. Her home, much like her life, was nothing less than extraordinary.

If you came after a certain hour, or indeed, early enough in the morning, you might be swept into the château’s private nightclub. The house’s innards were a worthy match for its exterior grandeur; it was the apotheosis of art deco design, with bathrooms in the style of Lanvin and Dior perfume bottles, a theatre and menagerie. It was a tribute to style that can’t help but recall the Marchesa Casati, who was, after all, a contemporary of the castle’s inhabitant. During the war, the residence took on the role of a safe house, hiding refugees, Jews and members of the resistance. In the 1960s Brigitte Bardot spearheaded a national television campaign to rescue the château – which was falling into disrepair, its owner into financial chaos – but it was sadly unsuccessful; the house was sold and its owner evicted. Today it still serves partly as a museum to Baker, whose own life was even more fantastical and turbulent than that of the building.

Defining Features

Few have captivated Paris as utterly as Josephine Baker. In 1975, tens of thousands of people crowded the streets to watch her funeral procession, in a vast display of public mourning. It’s often said that she was the highest-paid performer in Europe at one point, and it can be all too easy to miss just what a feat this was. Baker grew up in the St. Louis slums; she was born poor; she was a woman; and she was black. It is difficult to comprehend the vast difficulty that this particular combination meant in early 20th-century America.

All the same, in 1919, at the age of 13, Baker joined The Dixie Steppers, where she worked as a dresser. Her appearance, as a dark-skinned slender woman, was not deemed palatable for white audiences, and meant she was not permitted to dance as a chorus girl. Still, Baker learnt all the routines anyway and, when the company found themselves lacking a dancer she proved more than capable. Her charismatic and humorous performances quickly garnered attention. It wasn't until after Baker embarked for Paris, however, and the reputed Revue Nègre, that her success really began. Europe was enthralled, and her witty, decorative and sensual performances paved the way to widespread fame.

Seminal Moments

By the 1930s, Baker was a film star (she became the first black woman to star in a major motion picture in Zouzou in 1934) and a chanteuse, as well as a dancer whose performances entered into the mythical fabric of Parisian bohemia. She possessed a spectacular wardrobe, and more curious accoutrements included a pet leopard. She was famously proposed to on around 1,500 occasions. Her fandom was immense – often terrifyingly so. Whilst on tour in Croatia, one obsessive devotee pulled a knife out as she left a club – not to attack her, but to wound himself in a tributary act.

Baker being Baker was not sated by the prospect of being the heroine of any tawdry old rags-to-riches story, however. She was in many respects an activist at heart, and though she might have attained certain comforts that she had been hitherto denied, she remained deeply concerned by the depressing reality of race in America. She had made Paris her home, having found acceptance and a certain degree of liberty there, in spite of constant reminders that these were not widely available to women of colour. Even in Paris, it was not unknown for her to be heckled by American tourists, and a hotel manager once refused her a suite because he was scared of the reaction of American guests.

On returning to America in 1936, she was met by a racially hostile media. While she was largely idolised in France, she was now expected to use the servants’ entrance in hotels and found herself insulted by other guests. The performer saw that little had changed since leaving. The denigration of black people was only too manifest in the continuing poverty, segregation and bigotry.

As well as her occupations in singing, dancing, and acting, Baker was to also excel as a spy. During WWII she worked for the French Resistance, concealing messages written in invisible ink on sheet music, as well as reporting information she gathered from various unsuspecting officers, diplomats and other high-ranking officials. It was also at this point, as France became occupied by Germany, that she utilised Château des Milandes as a site of covert operations.

Following the war, her activism and engagement in the Civil Rights Movement back in America gathered momentum; she became involved in international public media battles, and due to her repudiation of segregated venues, became the first black performer to take to the stage in front of an integrated audience. On one occasion, backed by her friend Grace Kelly, then Princess of Monaco, Baker publicly boycotted the celebrated Stork Club. The media skirmish which ensued almost caused her to have her visa revoked by the State Department.

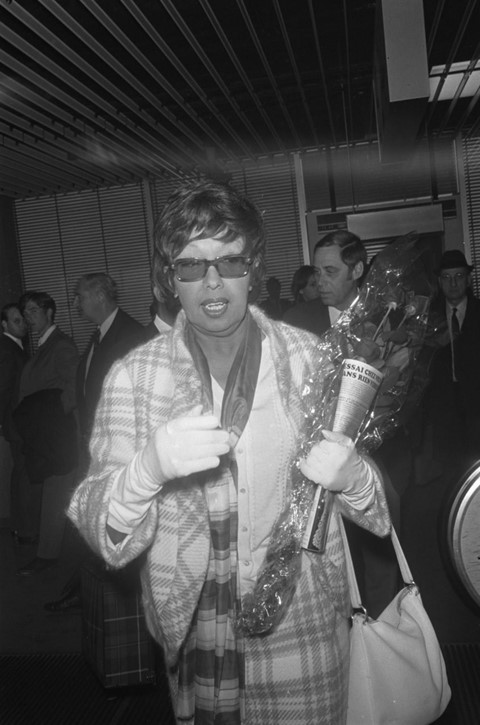

Back in France, Baker’s finances were in disarray, partly owing to her generosity, which was often abused. She lost her beloved Milandes, her “Sleeping Beauty castle”, and had to be physically removed from the estate. During the following period she fell into a poverty almost reminiscent of her youth, and was often seen wandering the streets. By the 1970s Baker was still performing and returned for the last time to America to give a final show which was received with a warmth she could never have anticipated after her experiences with racial prejudice there. In 1975 Josephine gave a final, exhausting, triumphant performance in Paris. She died a few days afterwards.

She's AnOther Woman Because...

Whilst both her activism and espionage have been recognised, it is only in recent years through feminist and cultural theory that her performances have been rightfully reappraised. These highly artful, self-conscious spectacles showed that Baker had a profound awareness of racial-sexual otherness, something she both continuously challenged and played upon.