Was there any significance to the fact that, not long before the much-anticipated announcement of a 2017 Comme des Garçons show at the Costume Institute of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the words Rei Kawakubo used to describe her collection were “invisible clothes”? She is the second living designer ever to be honoured with her own retrospective at the gallery, testimony, if any were needed, to the scale of her influence. Kawakubo, who has done so much to shape the modern wardrobe, is also passionately anarchic, however; throughout her career she has refused to kowtow to fashion industry systems, preferring instead to follow her own path, and by so doing she has created a fashion empire that is the envy of many. That too is hugely inspiring. Her company supports and nurtures young designers, giving them the time, space and backing to develop, while it is more common elsewhere for fledgling talent to be forced into the spotlight too soon: Junya Watanabe and now Kei Ninomiya have both grown to be brilliant in their own right under her watchful eye. Dover Street Market, which has revolutionised the retail environment, houses many more emerging names who are not part of the Comme des Garçons stable, selling their fledgling collections alongside giants, including Comme des Garçons itself, and any number of international big brands as if it were the most natural thing in the world. That too is, in fact, far from the norm.

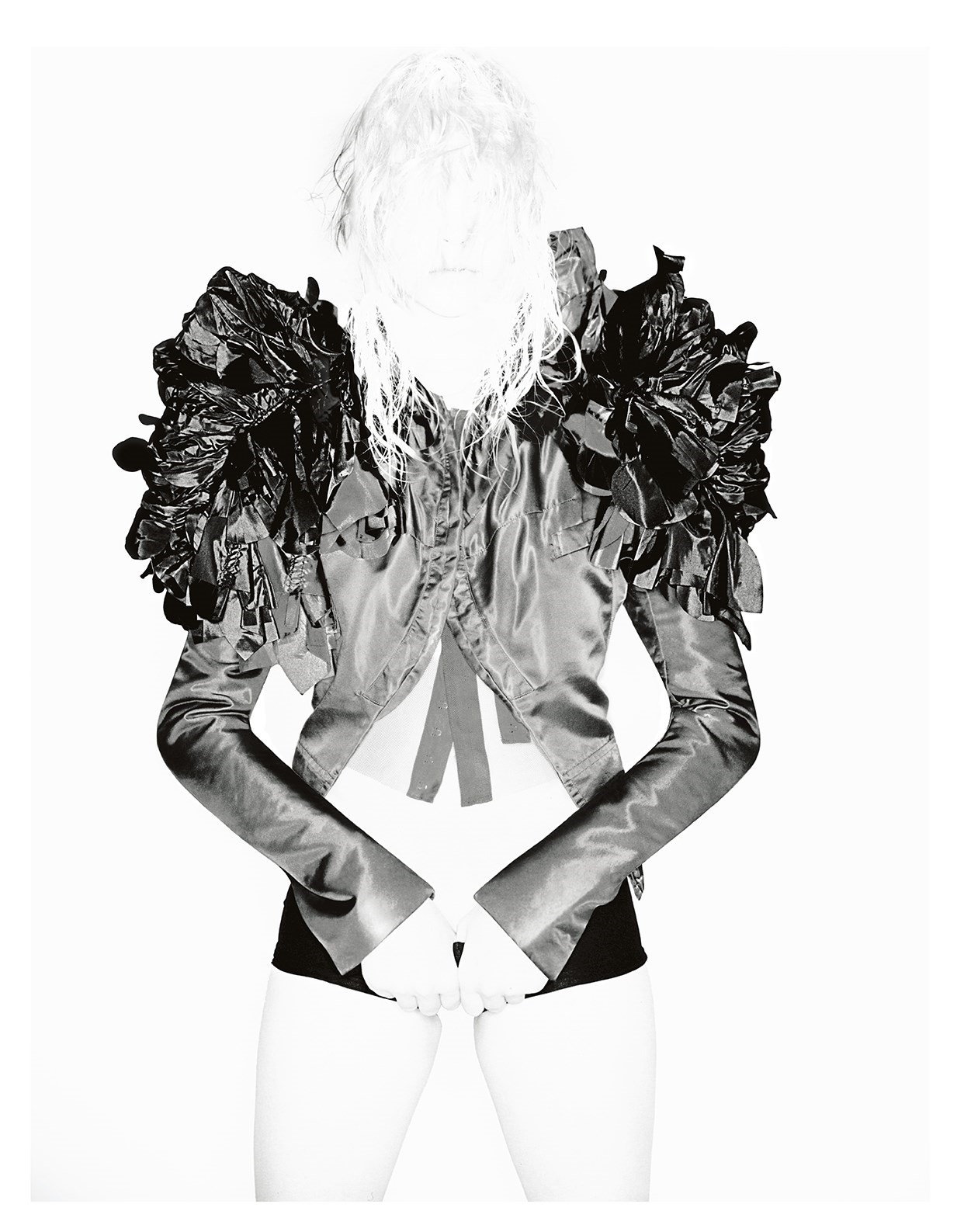

Kawakubo’s clothes are – of course – more powerfully subversive still. Will New York’s great and good step onto the red carpet at the gala ball that traditionally opens this exhibition in any of the monumental structures the designer showed on an elevated circular catwalk in Paris on Saturday evening? It’s hard – but rather wonderful - to imagine that happening. The designs in question were, as they always are, extraordinary: enormous, flattened shapes with the ghost of a body shape traced into them, more that revealed protuberant vinyl bellies or were padded around the breasts. At times, models’ faces were covered entirely: one piece in particular had a hood that opened and closed: pulsating, reminiscent perhaps of a beating heart.

For Comme des Garçons devotees – and there are many, many of these – the familiar signatures that have long fascinated this designer were all in place: the oversized frills and bows, the Peter Pan collars, the hearts, the tartan, the black and the red. “Red is black,” Kawakubo announced way back when, believing that black (thanks to her, incidentally) had become ubiquitous to the point where it had lost its strength as a statement. She reinvented it as the shade for women – and indeed men – to wear in the early 1980s, when she was first invited to show in Paris, investing it with a kudos not seen since it was adopted by the grandees of the Spanish court in the 17th century. Not that there was anything obviously status-driven about her work then as now. Instead, her early distressed designs over-turned any preconceptions surrounding that too. Her love affair with the non-colour has never really gone away, though, and it was especially prevalent this time around.

The idea, then, according to the powers that be at Comme des Garçons, was to break down the space between a garment and the person wearing it so the two became one. That relationship is similarly something that has preoccupied Kawakubo for decades. Her Spring/Summer 1997 ‘Body Meets Dress, Dress Meets Body’ collection was an exploration of that territory. More generally, the tendency to envelop the body over and above exposing it that was once so revolutionary, and has now been embraced not only by other designers but also by women who would rather not play arm candy the world over, may have its roots in Japanese culture, but it was established as an integral part of contemporary fashion here.

This collection was, as the characteristically brief and elliptical notes stated the following morning, “the most pure and extreme expression of Comme des Garçons imaginable”. It was all the more moving for that. The sight of young women engulfed in quite so much cloth spoke of protection, but also of a life devoted to fashion that has not always been easy. The fight to renew and continue to challenge her audience each and every season, as anyone who has ever met Rei Kawakubo will know, has been a difficult and at times even painful one. In recent years, she has addressed it by showing collections that look more like living sculptures than anything resembling clothes. They sell to museums, collectors and the odd person brave enough to actually wear them, while the more obviously wardrobe-friendly pieces are available to be seen by buyers and press in the Comme des Garçons Place Vendôme showroom.

With Andrew Bolton, head of the Costume Institute, and US Vogue’s Anna Wintour front row this was perhaps the most potent example of the establishment meeting the anti-establishment that anyone observing fashion and its impact on culture more broadly could wish for. There is nothing more establishment than the Metropolitan Museum of Art, after all, and nothing more anti-establishment in this industry than Comme des Garçons. That Rei Kawakubo’s archive will soon be shown in a space that will be visited by hundreds of thousands of visitors, many of whom will see it for the first time, is uplifting, as is the fact that the courage, strength and endless creativity that has gone into its making will be celebrated in so auspicious a manner.