50 years after the foundation of the African American revolutionary party, we take stock of the heavily politicised sartorial codes which played so key a role in it

The Black Panther Party has long been subject to heavy misrepresentation. As their white contemporaries became the poster children for counterculture, it was black activists who suffered the brunt not only of a figurative media backlash, but also of a literal, physical one. Understanding the party’s name is key to dispelling one of many myths surrounding it – a media depiction of mindless thugs looking to incite violence whenever possible; the panther was chosen as a symbol specifically because it does not strike first.

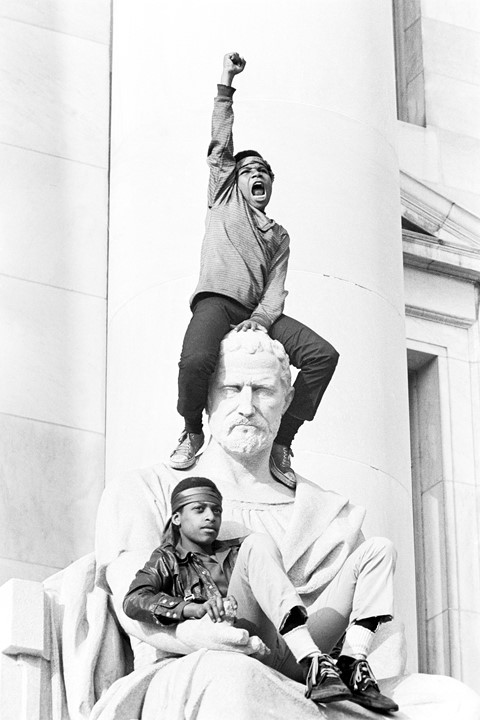

Of course, it is inherently problematic to consider a counterculture in terms of style, and even more so when that group is marginalised. Nonetheless, one cannot completely understand the Black Panthers without comprehending their style – of dress, of speech, and of activism. It was important to the group when so much was at stake, and what emerged was some of the most iconic and visionary art, fashion and culture of the era, which has not ceased to inform us today.

Formation

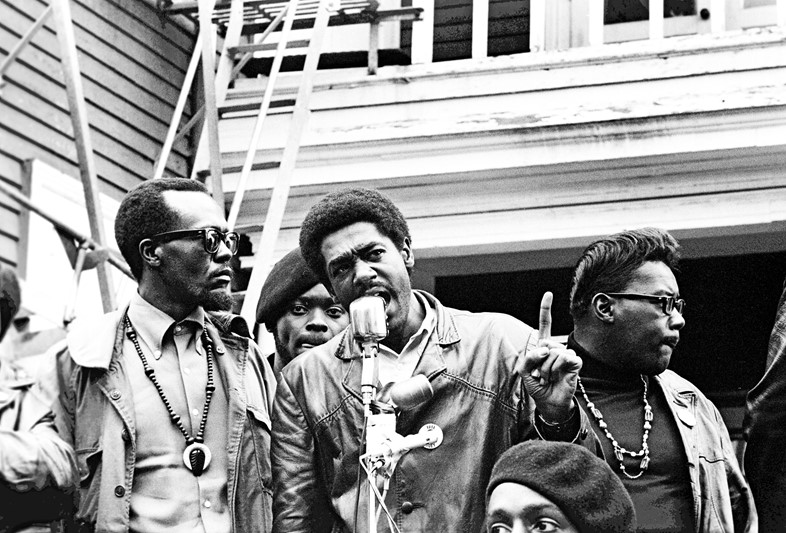

The Black Panther Party was formed on October 22, 1966 by two young activists – Bobby Seale and Huey Newton – and emerged from the wake of the Civil Rights Movement. The era, which had ended legal segregation, had also left a climate of empowered but disenfranchised black youth. Black Americans still suffered from the economic and physical brutalities imposed upon them. White supremacy still dominated the societal landscape. Violence against black communities was relentless. It is to this end that the party was originally formed– to patrol and provide necessary protection from racist police attacks. As the book states, “the Black Panther patrols galvanised the community and gained nationwide attention by ‘policing the police’.”

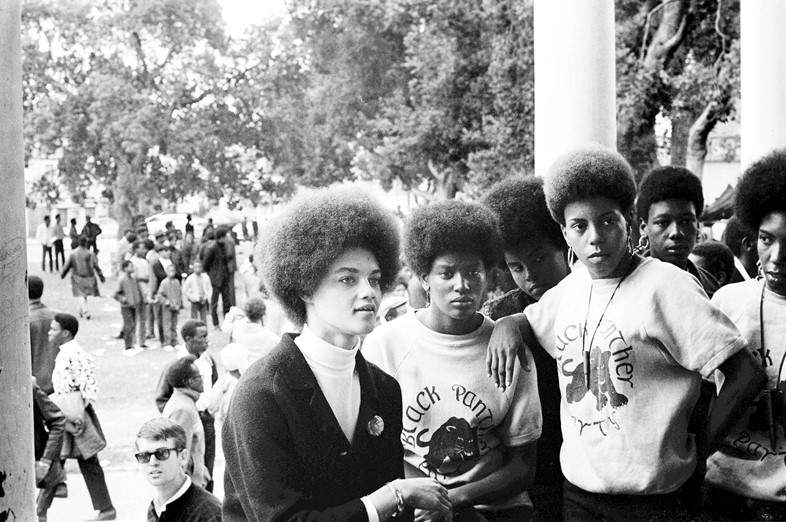

Informed and uniformed – they were known to carry law books – these patrols sent out a very powerful message. “Leather jacket and blue shirt. I made it the uniform when we founded the party,” writes Bobby Seale in his new book, Power to the People. He explains the origins of the Panther uniform in reference to the famous blues song (What did I do to be so) Black and Blue? originally written by Harry Brooks, Fats Waller, Andy Razaf. “I’m saying the American community is all beat-up black-and-blue from over 200 years of racist discrimination... Now, let’s make this the uniform.”

Likewise, the beret was to become an important signifier. Two weeks after devising the uniform, Bobby Seale, inspired by a film about the French underground resistance, decided black berets would make for a striking addition. “It’s a militant image, which appealed to people, and it also scared police,” he writes. The Party were conscious of the symbolic and militaristic connotations of the beret, and what they were presenting was a united whole – a solidarity which could no longer be bullied, divided and conquered.

Rise

“The Panthers electrified a generation of black youth,” states Power to the People. As the party grew from six members to over 10,000, it also developed from a self-defence group into a political revolutionary organisation, aimed at furthering civil human rights for everybody. They set up programmes providing free breakfasts for children and free healthcare, and gave away shoes, clothing and food on a nationwide scale. They also protested for the exemption of black people from military service – refusing to be used, as people of colour had been used for centuries, to fight wars they did not agree with.

A core of young visionaries, intellectuals and artists came to forge and re-forge the black Western identity. Key to this was the eschewal of Eurocentric beauty ideals, which had for so long enforced the notion of blackness as unattractive. Kathleen Cleaver (the first woman appointed to the Panther’s Central Committee) spoke out: “All of us were born with our hair like this and we just wear it like this because it’s natural, because the reason for it, you might say, is like a new awareness among black people that their own natural appearance, physical appearance, is beautiful.” Natural hair became political; a symbol of defiance, but also of self-acceptance.

Fundamental to the Panthers’ popularity amongst the left was the fact that they sought to form coalitions with various marginalised groups, including the queer and feminist movements – something that could not be said of other radical and left-wing groups, which were fraught with the misogyny and homophobia of the era. While the Panthers had their issues, women were its driving force, making up over half of its number and occupying prominent positions.

The Panthers’ immediate influence was discernible amongst other revolutionary groups and intellectuals, many of whom admired both what the party were doing, and the style with which they were doing it. Fashions were adopted alongside ideas. The polo-neck is a particularly interesting example of this – its association with the Panthers popularised it, and while it was thought of as Beatnik attire before they adopted it, it was the black jazz and arts scenes of the 1930s in Europe and the US which gave rise to so much of the language, aesthetics and fashions which came to influence the likes of the Beats and European intellectuals.

Legacy

By the late 1970s, the group’s membership had significantly declined. As was to be the case for so many countercultures, various aspects of it were to be adopted and diluted for popular culture after its radical centre was ‘extinguished’. The party’s open door policy had been taken advantage of: informants were sent in by the F.B.I. with the sole aim of neutralising the group. The most prominent members of the party were victim to ruthless government tactics and constant harassment, whilst others were ultimately killed by police.

The legacy of the party is a living one, having introduced forms of cross-sectional politics which came to define the future of activism, as well as models of community action which continue to be utilised today. Their cultivation of style and the arts was not only to disseminate into popular culture, but to redefine it, making it possible for the first time in a long time for blackness to be viewed not only as beautiful, but as cool, intellectual, and powerful.

Power to the People: The World of the Black Panthers is released October 18, 2016, published by Abrams & Chronicle.