The image I hold in my head, always, of Azzedine Alaïa, is that of an inventor rather than a couturier. When you talk to Alaïa about the fashion he admires, he cites names like Cristóbal Balenciaga, Madeleine Vionnet, Madame Grès, Charles James. All eschewed the limelight; all invented. All, also, worked on their own clothes with their own hands – in every Balenciaga collection, there was a black dress created entirely by Cristóbal himself. It was the one to watch because it rang in the season’s changes, however infinitesimal they may be.

The hallmarks of that aforementioned pantheon of greats have slipstreamed into the general fashion consciousness: the bias-cut was Vionnet’s, but it now belongs to fashion as a whole. The same is true today, of Azzedine Alaïa. Alaïa created his first collection in leather, ergonomically seamed and erotically charged, defining the lines of the 80s before they had even begun. He was the first couturier to stud garments with metal for decorative effect, while his experiments with the technical possibilities of knitted fabrics helped reinvent the very notion of fabric in fashion. Alaïa crafted clothes that negated underwear – although that was indicative of virtuoso dressmaking rather than sexual technique.

"Who can really say who invents something first in fashion?" Alaïa himself asked, in an interview back in the early 90s. If Alaïa’s clothes defined the 80s, I’d argue that they invented the 90s. His experimentation delineated the decade’s all-important stretched-out surfaces, brief silhouettes, and clinging garments that were easy to wear, but difficult for your body to live up to: leggings, bandage-wrap dresses, catsuits and bustiers, with a revival of the padded underwire brassiere that would go on to spawn a multi—million pound empire under a brand name crushing together “Wonder” and “Bra,” like Eva Herzigova’s cleavage in their 1994 “Hello, Boys” advertisement. That portmanteau proved inescapable by the end of the decade – but Azzedine Alaïa got there first.

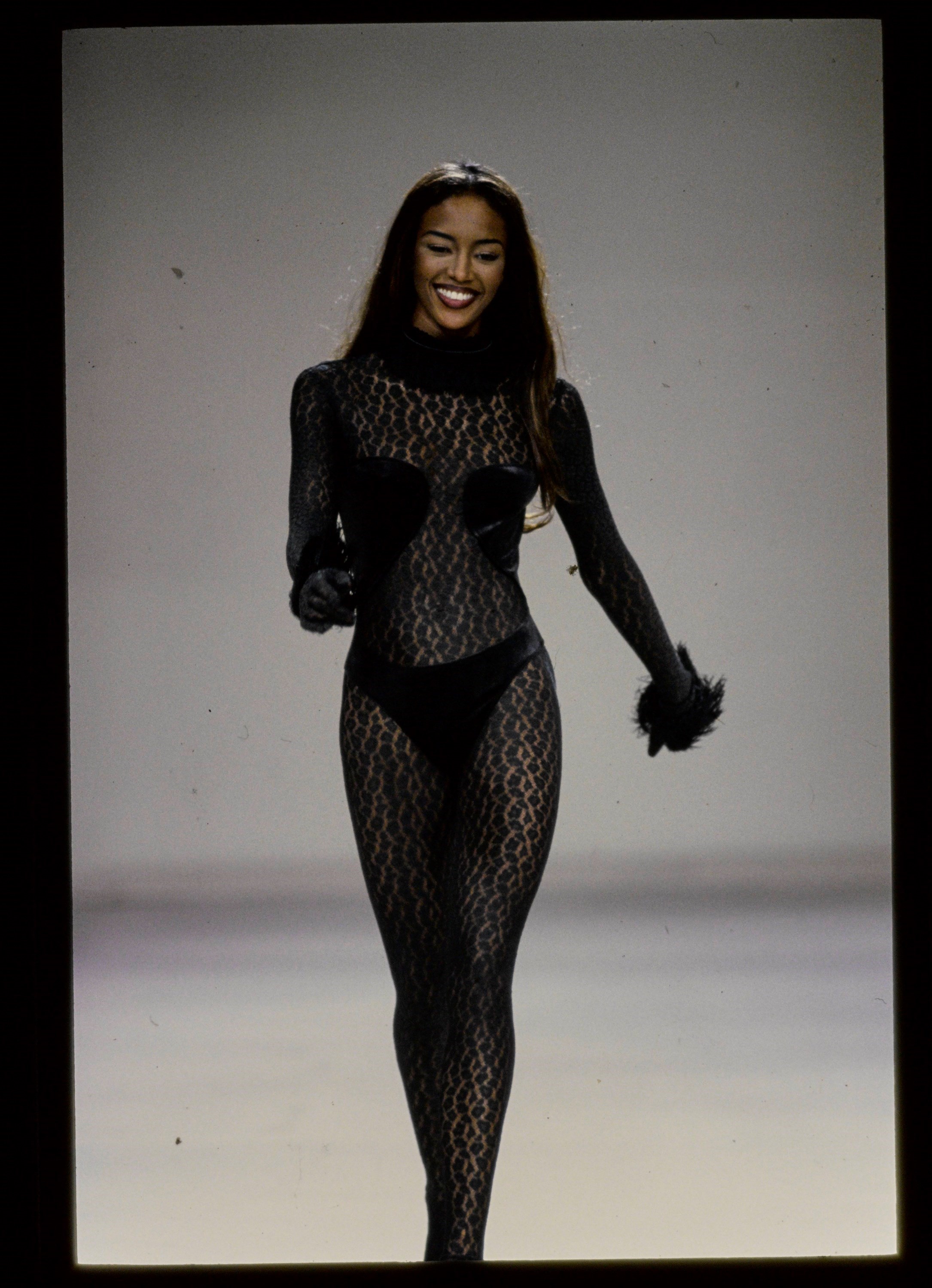

He also invented the Supermodels, giving models like Stephanie Seymour and Naomi Campbell (then aged just 16) a home away from home in Paris; in return, they would break other bookings to model in Alaïa’s clothes, their appearances covered not by the astronomical fees charged to other labels, but by armfuls of clothes that made even these most beautiful women in the world look more beautiful than any other garments. As advertisements go, that was even more potent than Eva’s poitrine.

Today, Alaïa is still inventing, and reinventing, in his studio on the Rue du Moussy, where he has been based since 1990. At the dinner Alaïa threw in that studio, celebrating AnOther Magazine’s Autumn/Winter 2016 issue during October Paris fashion week, the designer told me that if he had two new ideas a year, it was “genius”. Alaïa’s clothes have an eternal quality that bear that assertion: he doesn’t need novelty. Rather, he refines and reinvents, spinning out his signatures into fresh iterations and experimentations, using something old and making it new.

Hence, when looking at Alaïa’s spring/summer 2017 collection (shown on a classic Alaïa timescale – namely, almost three weeks after every other designer in the world), it’s easy to reference back to pieces past. But this isn’t about revival, nor even a remix: what Alaïa does, each season, is to invent these ideas anew, to approach them with a different spirit and eye. Alaïa classics never become staid.

“Eternal” is the word thrown about by people a great deal when discussing Alaïa's clothes – including me. What we are trying to articulate is the improbable fact that a dress you bought in 1991 would look just as good today, the same way that Vionnet and Grès draping still looks modern. Come to think of it, so does an Ancient Greek chiton, if draped right. Perhaps Alaïa’s reinventions are a way to keep us coming back for more of his timeless clothes – the other major factor in Alaïa is that it’s all made so beautifully that it will survive a lifetime. As if to prove both of those points, there’s a ferocious trade in second-hand Alaïa on eBay, all still looking great, stylistically and physically. Perhaps it’s best to describe Alaïa not as an inventor, but an alchemist: his work is to spin the base materials of clothes – leather, viscose, cashmere – into something akin to fashion gold. Here are a clutch of key Alaïa spring/summer 2017 design motifs, mapped back through his own archive of design signatures. At Alaïa, everything is always and never the same.

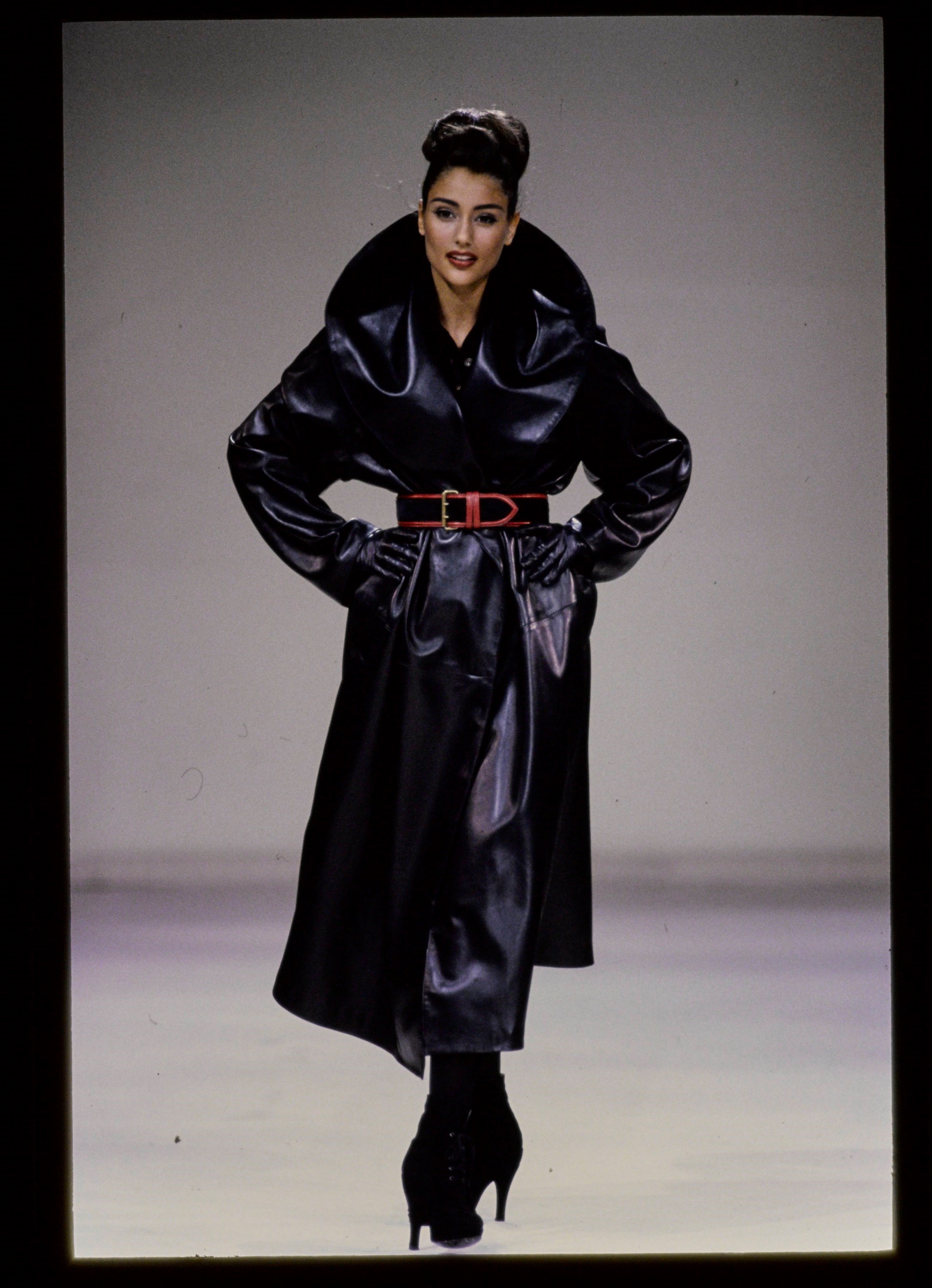

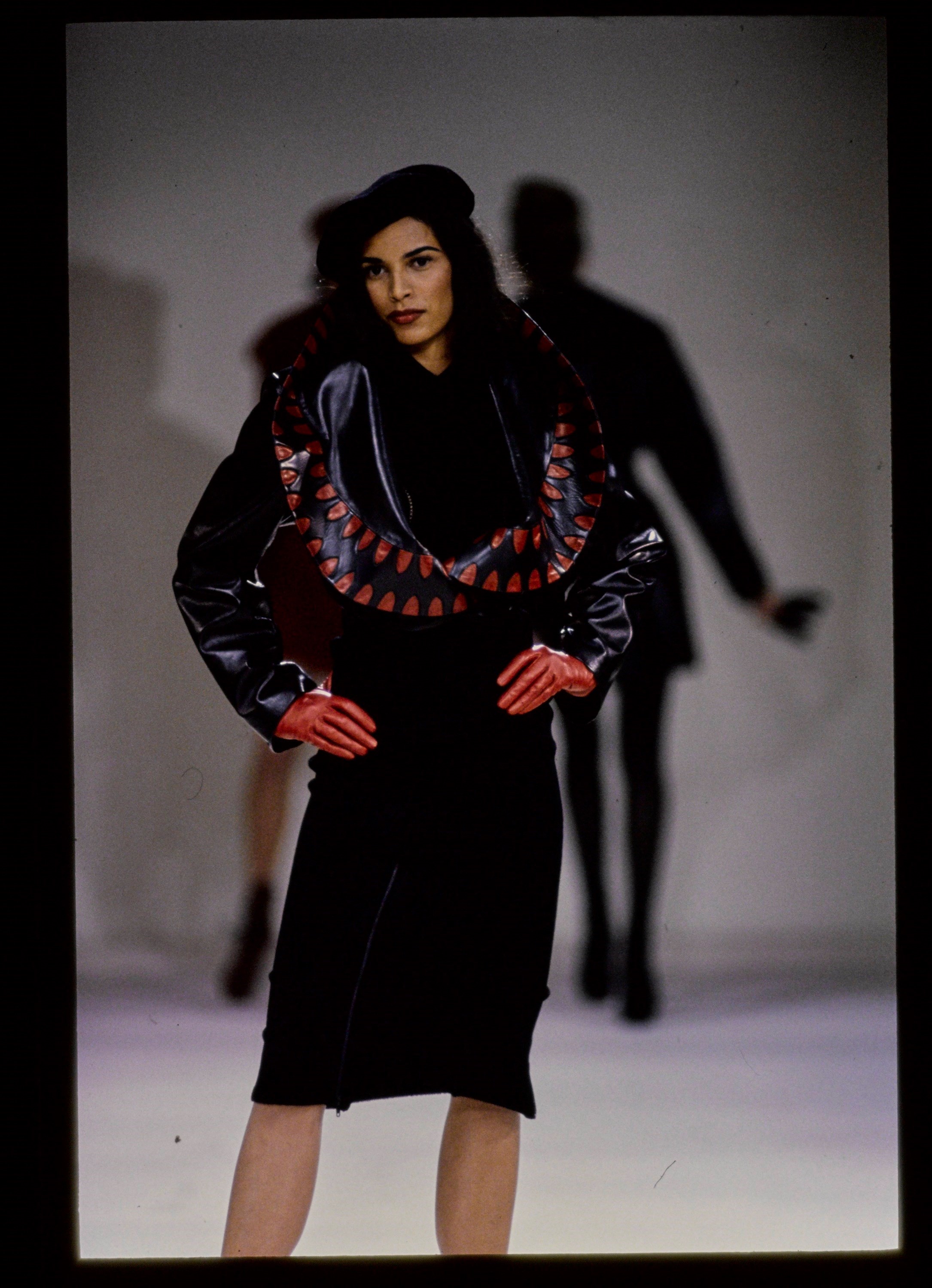

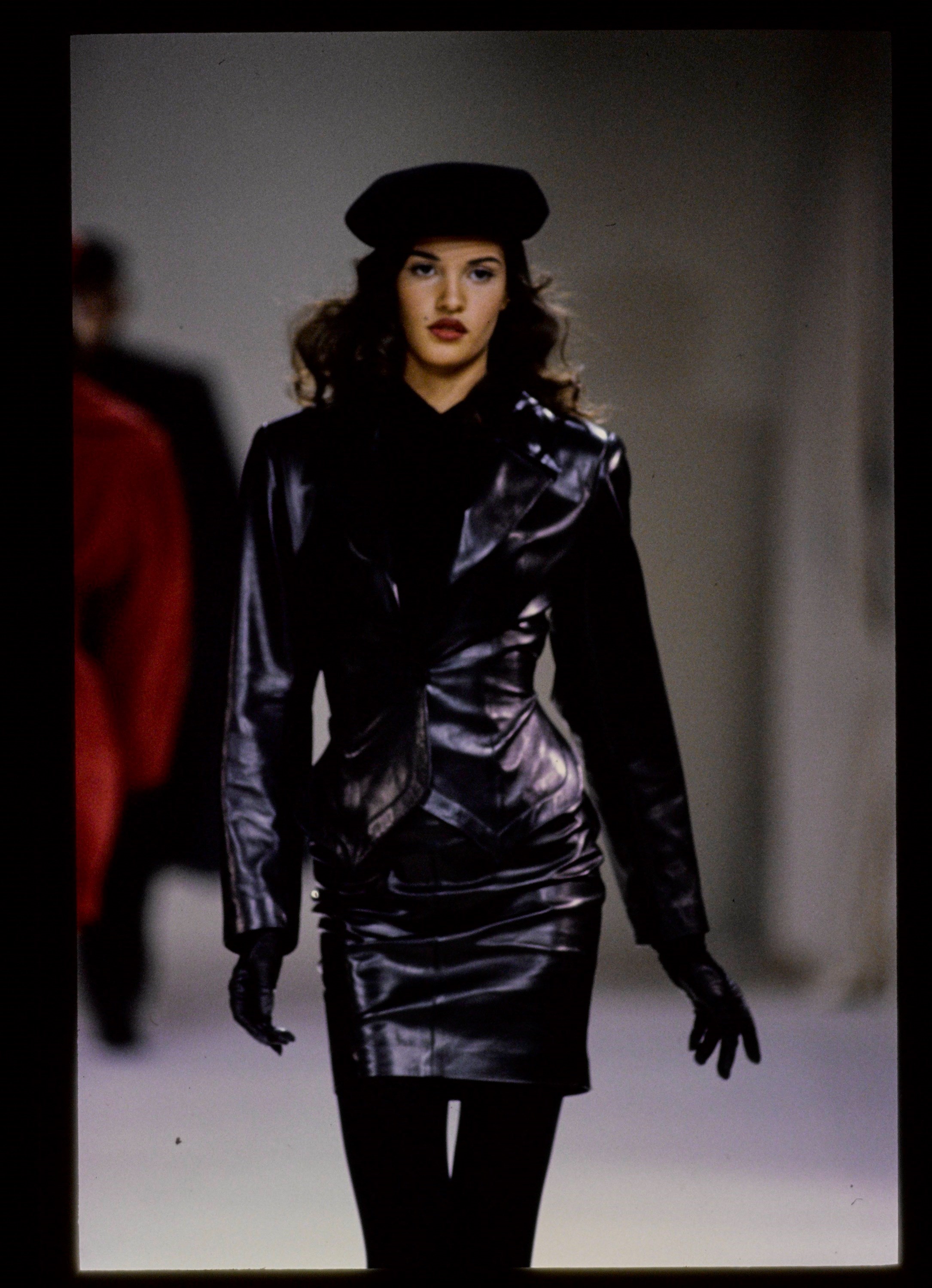

Leather

Azzedine Alaïa made his breakthrough onto the fashion scene with a collection of leather garments, originally designed for Charles Jourdan in 1979. Jourdan thought it was all too tough, according to Monsieur Alaïa (via a 2012 profile in Vanity Fair) – evidently they didn’t recognise the shifting fashion mood of late-70s and early-80s Paris. The collection wound up on the cover of French Elle, whose staff wore Alaïa to the Paris collections in 1980: slinky knits, grommet-studded chiffons and, of course, curvy leather. The fabric became an Alaïa staple. The toughness of leather, however, was softened for Alaïa’s latest collection: indeed, the leitmotif of this outing was a gentleness and airiness, most striking when achieved through uncompromisingly hard fabrics: here, via his superlative technique, Alaïa injects leather with the suppleness of silk.

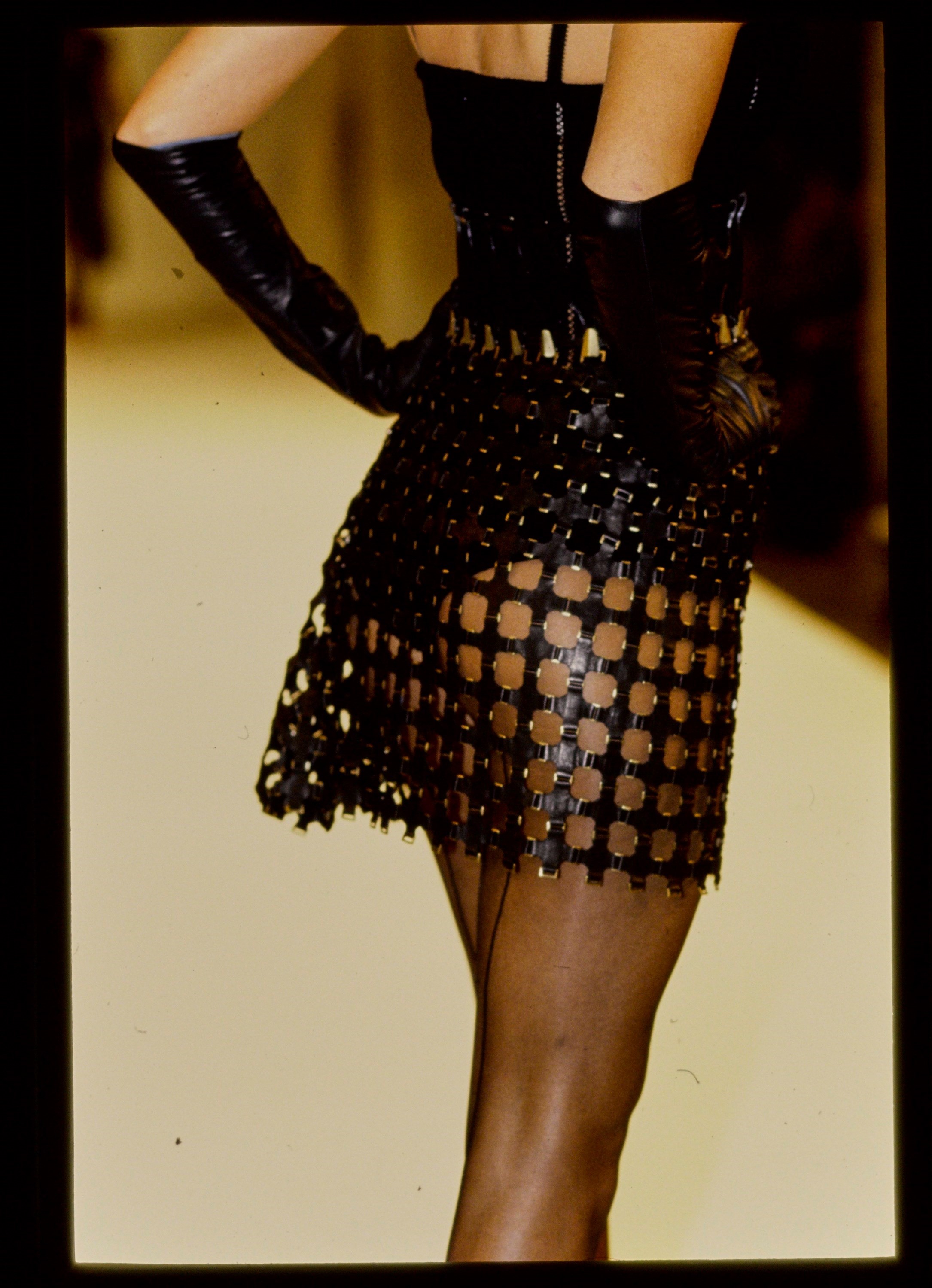

Studding

The coat on the cover of Elle was studded with grommets, an idea now commonplace because of Azzedine Alaïa. He was the first to punch metal through clothes for decorative rather than functional purposes: metal eyelets were more commonly used to fasten corsets; studs to strengthen seams. Alaïa used them in some of his earliest plays of peekaboo, adding a fluidity to heavy fabrics like calfskin or boiled wool, or giving a hard edge to fabrics like chiffon or georgette. Alaïa even studded a wedding dress with them for his autumn/winter 1986 collection; while, five years later, he used metal bindings to create “grillwork” dresses that formed leather cages around his models’ bodies. His studded dresses for spring/summer 2017 are soft knit – but the studs penetrate through the fabric, rather than being applied to the top. Keyed into the fibres, they add a weight and heft to the dresses; others feature grommets studded into dense knit to create a fabric that resembles a modern chainmail. All are applied individually by hand.

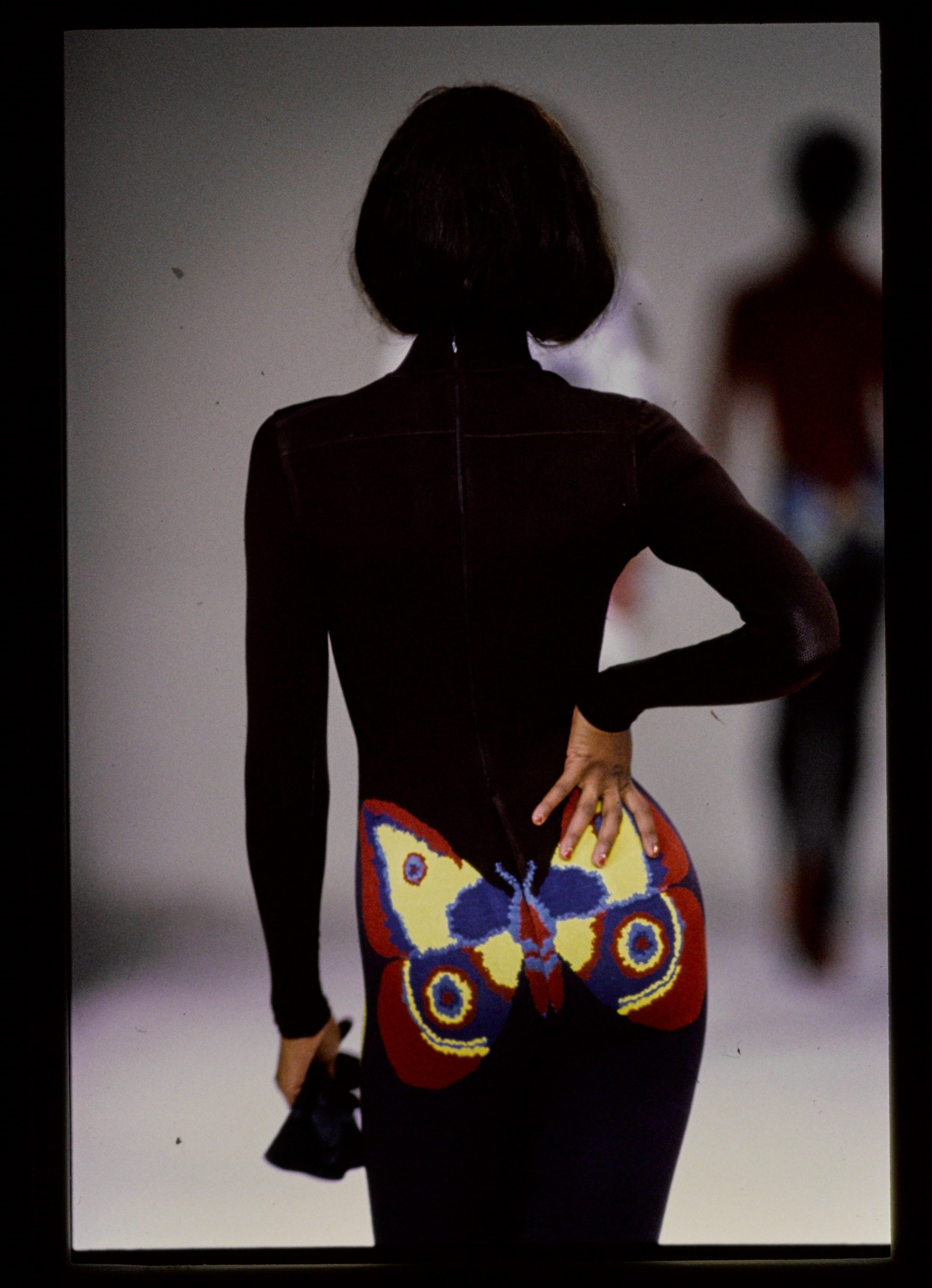

Jacquard Knits

Azzedine Alaïa’s expertise and ongoing experimentation with knitwear techniques is legendary. Silvia Bocchese, an Italian specialist, has worked with Alaïa for over 40 years and, in a 1991 interview for the International Herald Tribune, Alaïa recalled that he had used stretch materials to shape the inside of garments he made for private clients, including just about every fashion-conscious female member of French high society in the 60s and 70s, as well as the movie stars Arletty and Greta Garbo. “Then I just started using them on their own.” No small feat was the knitting of intricate jacquard designs into knits; a way of decorating the body, without affecting the technical hold and stretch of the knit they are keyed into. They wound up almost like tattooed clothing, designs built into the very pores of the dresses that hold the body as a proverbial second skin. Alaïa tends towards simple designs, or motifs taken from nature: in the past, butterflies and animal spots were key, as well as, perhaps, graphic stripes; for spring/summer 2017, the technical marvels knitted into these magical dresses (often with shape achieved, incredibly, without seams) were simple polka dots, and floral patterns, across dense knit dresses, skirts and fluid capes.

Transparency

The sensuality of Azzedine Alaïa’s work relies on the body, so opening windows onto it seems only natural. Peekaboo effects are something he’s toyed with throughout his career – such as the instantly identifiable 1986 design with a spiral zipper snaking across breast and flanks, or the intricately laced bandage dresses, with slithers of skin strategically displayed between every ribbon of material. For spring/summer 2017, rather than cutting open his dresses, Alaïa once more turned to knitwear, inserted semi-transparent stripes or panels into his dresses, revealing intricate layers beneath – perhaps popping with a pattern or colour, like the grillwork “cage” dresses of 1991. They looked great then; these look great today. They’ll all still look great in perpetuity. That’s what the word “eternal” is really all about.