Unapologetically arrogant and endlessly eccentric, we recall the brilliance and certitude of a great American artist who carved her own path within the male-dominated New York art scene

“I never for one minute questioned what I had to do,” said Louise Nevelson when asked about her long struggle for artistic recognition. “I did not think for one minute that I didn’t have what I had… if you know what you have, then you know that there’s nobody on earth that can affect you.”

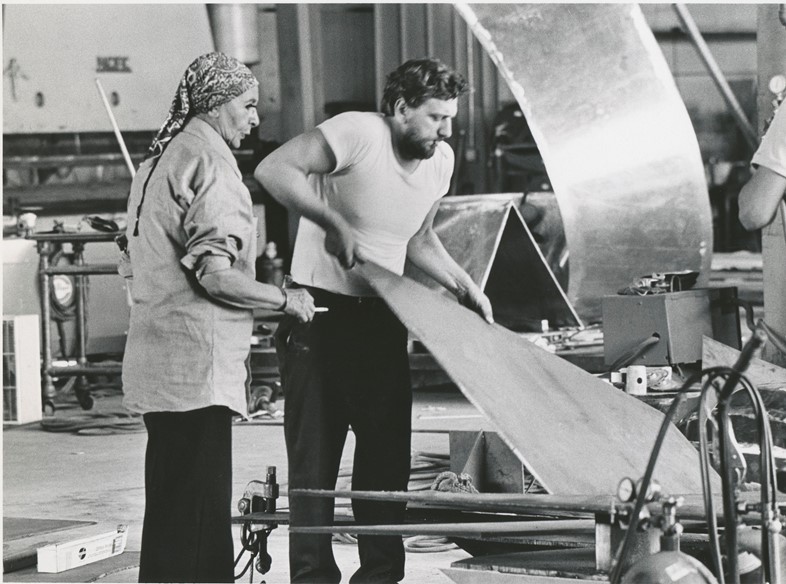

Nevelson is now considered one of America’s most important artists, an ‘architect of shadows’ who brought about the birth of environmental sculpture with her enormous wall assemblages compiled from found objects and scrap wood, their delicate balance of dark and light building mystic narratives. However, her road to recognition was not an easy one. As a young, divorced woman in the 1930s the art world elite shunned her, even when she gained the support of influential dealer Karl Nierendorf. While many criticised her sculpture, far more condemned her unapologetic arrogance, eccentric sartorial choices and voracious sexual appetite. She was a woman before her time, and it would take decades for her talent to finally be recognised.

Defining Features

Nevelson’s distinctive style was as notorious as her work. From a young age she was keenly aware of her astonishing beauty, and was well versed in the art of putting on a show, learned from her mother’s stubborn dedication to preserving traditional forms of Ukranian dress, even in rural Maine. Nevelson’s obsession with elaborate headgear earned her the nickname ‘the hat’, although as she grew older (and more celebrated) she was even better known for her enormous mink eyelashes, outlandish sculptural jewellery and gigantic fur coats. When asked about her outfits, she stated “every time I put on clothes, I’m creating a picture.” For Nevelson, every aspect of her life was art.

Seminal Moments

Nevelson was born just outside Kiev, but her family soon fled in order to escape intensified Jewish persecution. Once in the US, she was acutely aware of her position as an outsider and married young in order to escape to New York City – a decision she later regretted: “marriage is like a chain… I think to go to bed with a man, every night, like a husband, must be a nuisance.”

Although she had a young son and a reasonably comfortable life, Nevelson abandoned her family and lived in paucity, borrowing money from her parents and siblings in order to pursue her art. She soon ran in all the right circles, counting the greatest artists of the day such as Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko, Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo among her friends. Many of her exhibitions were reviewed favourably, but she rarely sold any work and struggled to be taken seriously. With little money and few prospects, she continued to work tirelessly, filling her home to bursting with countless ‘shadow boxes’ that she often pulled apart and reassembled to create new walls of sculpture.

Towards the end of the 1950s, Nevelson reached a breakthrough with her wholly immersive exhibitions, often set in low light to intensify the shadows. Her obsession with black paint created a new cohesion that redefined her work and amazed critics. As her star ascended, she experimented with variations in white and gold, but it was the addition of mirrors that allowed Nevelson to finally capture her deeply desired ‘fourth dimension’.

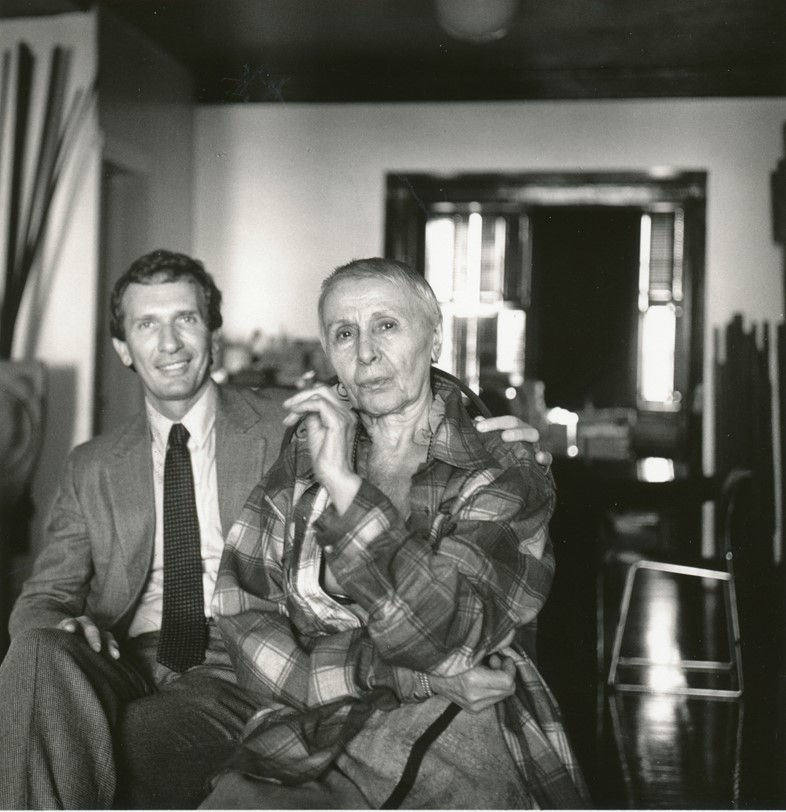

Finally, Nevelson was gaining the acknowledgment she knew she deserved, with the aid of the hungry young gallerist Arne Glimcher, founder of Pace. Not only was she critically applauded, but she was selling as fast as she could work, and was invited to show by the most prestigious museums and galleries in the world. In 1959 she was selected alongside Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly and Robert Rauschenberg for MoMA’s prestigious Sixteen Americans exhibition; she represented the US at the 31st Venice Biennale and in 1964 Vogue produced a 13-page feature on her work, presented alongside supermodel Verushcka.

Nevelson had arrived, and never looked back. She continued to work assiduously for decades, showing all over the world to international acclaim. Her final recognition came in 1985 – two years before her death – when she was awarded National Medal of Arts by president Reagan, along with the equally formidable Georgia O’Keeffe.

She’s AnOther Woman Because…

Nevelson never doubted her genius. Despite years of criticism and several false starts she was absolutely determined to play by her own rules and change the face of the art world, which she achieved not only through her groundbreaking sculpture but also her dazzling egotism and startling appearance. Her unfaltering conviction and late-won success redefined the perception of female artists in a ferociously male-dominated sphere.

Louise Nevelson: Art is Life by Laurie Wilson is out now, published by Thames & Hudson.