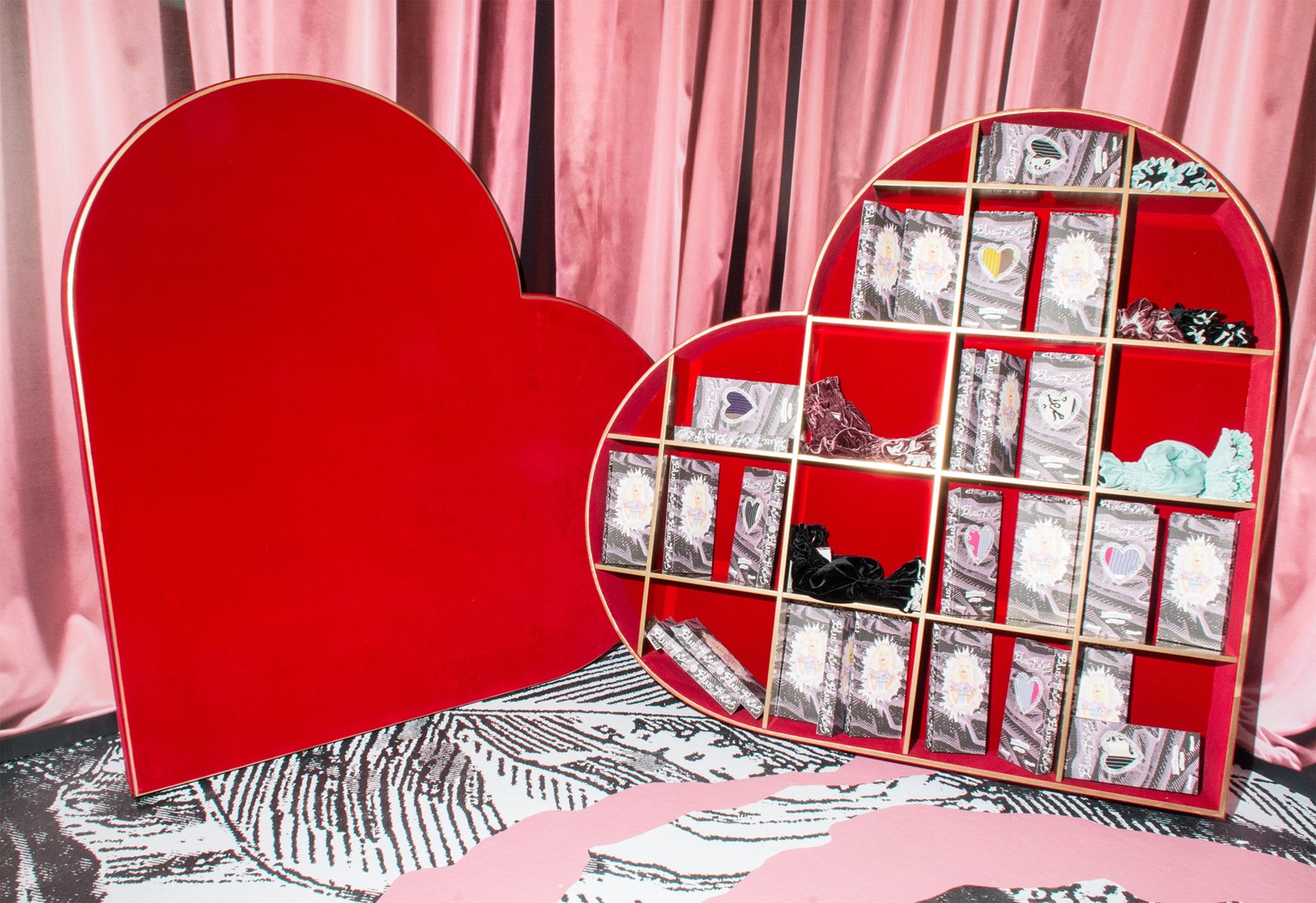

Tennessee Williams’ The Glass Menagerie is one of Edward Meadham’s favourite plays: the story of Laura Wingfield, a “sick, weird girl who collects glass figurines, who nobody spoke to at high school,” and whose nickname, Blue Roses, is a malapropism for her condition of pleurosis. “So, Blue Roses are sort of an analogy of not fitting into the world,” he explains, a few days before his new project, entitled Blue Roses, launches at Dover Street Market. “It’s a motif that I’ve used forever and ever.” Of course, such a sentiment – of speaking to outsider culture through overwrought, artificial beauty – bears clear parity to that which inspired Meadham Kirchhoff, his former label created with Benjamin Kirchhoff. So, too, do the pieces that comprise Blue Roses: the sweatshirts and T-shirts and socks and frilly cuffs and collars that he has created to arrive just in time for Christmas are printed with the same sorts of collaged visuals and scrawled phrases that once illustrated his former brand. “He is a designer of enormous talent with such a singular voice,” says Adrian Joffe, CEO of Dover Street Market – and Blue Roses might be a new project, but as Meadham once explained, each one of those MK collections “was comprised of a detailed self-portrait of my insides: my entire brain and everything I was” – and so it would be nigh on impossible for this new creative outlet to appear as anything else. “I’m still me; I haven’t turned into a different person,” he says.

However, visual parity aside, there are a few key differences between Meadham Kirchhoff and Blue Roses – first and foremost that there are no showtime theatrics, elaborate sets or heady clouds of Penhaligon's Tralala perfume surrounding these pieces: they are arriving straight onto the rails at Dover Street Market in a sort of see-now-buy-now fashion. Plus, it “is not a collection,” Meadham states, firmly. “The collections I used to do were based on these whole stories in my head; they had reasons, and meanings. This is not that.” Most importantly, though, is the fact that while MK pieces retailed for thousands upon thousands of pounds (those fantastical floating lace dresses went for similarly fantastical prices), a Blue Roses T-shirt goes for £48. As well as being a savvy economic decision – “nobody that I know has any money now” – it democratizes the brand in a way that just wasn’t possible before: while £48 might still be a lot for a T-shirt in ordinary spheres, within the realm of fashion it is certainly entry-point. “For all the world, I would love to have this full-scale atelier with all these people who can make these most amazing gorgeous things that we can all think are lovely, but for once it would be nice that someone can actually have it,” he says – and his fanaticism for Riot Grrrl culture, for handmade zines and Courtney Love and DIY activism, means that his is a brand for whom democracy is more important than most.

Meadham’s aesthetic, and all of the issues that it both references and champions, achieved peak renown during the period that DIY digital feminism really took hold of contemporary culture, establishing a sort of second wave of Riot Grrrl philosophies rooted in the global collectivity and grassroots empowerment made easier by the internet. In 2011, the same year that 15-year-old Tavi Gevinson founded teen girl online magazine Rookie, Meadham Kirchhoff presented a catwalk homage to 90s icon Courtney Love that not only drew its audience to tears, but was reblogged on Tumblr into digital ubiquity. Propagated by blogs and social media, there was a revolution emerging in how girlishness represented itself, weaponising and subverting prettiness in the same way that Kathleen Hanna once did – and Meadham Kirchhoff stood its fore, celebrating “fags” and “dykes” and “batty boys” and “freaks” with abundant glitter and sugary frills. Theirs was one of the first brands to embrace streetcasting, to present plus-size models on the runway, and they explicitly championed outsider culture rather than just courting industry elite (who, it must be said, were equally enamoured by their offerings). It was one of the greatest contemporary examples of fashion’s ability to be both pretty and powerfully political, and: “It was a sort of love letter to beautiful things, craft and subculture,” Meadham recently told AnOther. “It was for anyone who ever felt ugly and weird, or who didn’t fit into the expectations of the world that surrounded them. It was an invitation or encouragement for them to create their own world, their own ideas and their own voices.”

“I was 13 when I saw Huggy Bear on The Word, and it changed everything for me,” he explains now, of first happening across Riot Grrrl when isolated in West Sussex. “It’s the only thing that seemed really relevant – and it still does.” It is a coincidence, of course, that we are speaking in a post-Trump climate, but a particularly resonant one considering the current political situation. “Our world still really, really, really talks down to girls, and that’s partly what this is all about. There’s loads of stuff for boys, loads of stuff that’s affordable, loads of stuff that they can buy into. But there’s not really anything for girls.”

Of course, he’s right: politics aside, recent years have seen streetwear brands like Palace and Supreme and Gosha Rubchinskiy earn cult status by creating T-shirts and hoodies that offer markers of subcultural affiliation to their wearers, creating visible communities of like-minded individuals who queue for hours upon hours for their latest drops or form Facebook groups devoted to discussing their new purchases. Comparatively, womenswear has been surprisingly slow on the uptake – and, right now, it feels like wearing a badge of liberal, feminist positivity is more relevant than ever. But proclaiming your identity on your chest is scarcely a new phenomenon; not only have band T-shirts and politically-charged badges been the norm since the seventies, but “I was at Saint Martins when Raf [Simons] was putting things like Joy Division or the Manics on T-shirts and jumpers,” says Meadham. “It was so important for me to feel like there was fashion that actually related to me, and to other things. It made me think, well, this is possible.”

When I meet Ed to discuss Blue Roses, he’s wearing a Meadham Kirchhoff jumper from A/W11, one of the knitted insartia ones featuring a witch on a broomstick. It is a picture that was taken from the Hole promo flyer for Live Through This, and it looks like a Jill Murphy illustration: it’s that perfect blend of childhood twee and anarchic subversion that he is so particularly good at. There were always T-shirts, and jumpers, in those old Meadham Kirchoff collections – those punk ones scrawled with Batty Boy in S/S15, the collaged Riot Not Diet pastel ones in S/S12, the shimmering, glittery ones from S/S10 (those are actually reprised, long-sleeved, for Blue Roses). “Whoever made the T-shirt… well, how fucking clever,” he smiles. “Everybody wears T-shirts at some point or another. It’s the most democratic blank canvas possible.” Here, you get the sense that democracy is key; that, as much as the project is set to be a festive sell-out, it speaks to the roots of Meadham’s principles and embraces his core aesthetic. “At the end of the The Glass Menagerie, Jim comes to visit Laura and he knocks over her glass unicorn, breaking off its horn," he explains. "It’s kind of this analogy, of making her into a normal person by giving her his attention. My whole world is about not mending your horn, of not being like normal people. I don’t want to be the normal people. This is me.”

Blue Roses is available to buy now at Dover Street Market.