On the anniversary of the legendary poet's death, we chart her singular life and career – from her fiery conversation to her friendship with Marilyn Monroe

Edith Sitwell emerged as the ultimate eccentric in an age which produced an above-average number of them. This might be attributed to her descension from a notoriously outlandish family – one which included a mother who was sent to Holloway prison for fraud, and a father who wrote A Short History of the Fork, The History of the Cold and invented a pistol for shooting wasps. It might even be attributed to the fact that Edith was something of an authority on the subject of idiosyncrasies, having penned the history book English Eccentrics. Sitwell, however, stands out as an original not by virtue of association, but by sheer innovation. She went far beyond the image of the outlandish but anodyne country squire. Once described by Raymond Mortimer as “a dangerous Bolshevik, terror of the colonels, horror of the golf clubs and causing panic amongst dog lovers everywhere,” genteel England was ultimately anathema to her.

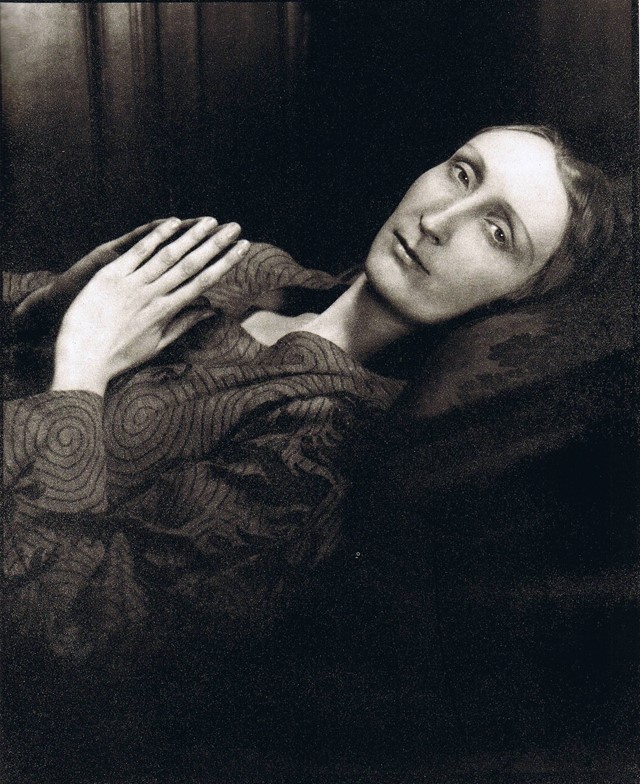

First and foremost Sitwell was a poet. She was a pillar of artistic life in London, and embodied what is now a generally underrepresented side of Modernism. “Good taste is the worst vice ever invented,” she said, ever at odds with dominant taste models whether they belonged to the establishment or the avant-garde.

Defining Features

Edith was both painfully shy and a brilliant conversationalist who could produce fierce, barbed witticisms when provoked (and sometimes when not). Perhaps this was because she was so often forced to defend herself. As a child she was subject to cold and often cruel parents. Her physical appearance was considered extremely odd, to the point of her father forcing her to wear a nose-truss to try and straighten it. And if her physical attributes caused concern, her intellectual interests were altogether loathed. Her love of poetry and music and her frequent flashes of precocity were deemed inappropriate by both parents, whose opinions on what was appropriate can be easily gleaned from a book her father gave her: How to be Pleasing, Though Plain.

This deeply unpleasant relationship with her parents made for an especially strong bond with her two brothers, Osbert and Sacheverell. The Sitwell trio became leading figures of London literary life. They were known – alongside being Modernist pioneers – for their wonderful conversation and ever-delicious gossip, boasting a social circle that reached from Virginia Woolf to Marilyn Monroe and cultivating a London-based artistic scene that was viewed as rivaling the Bloomsbury Group.

All three siblings wrote, but it was Edith who was to command the most attention. Her poetry garnered success and disdain in perhaps equal measures. As a young artist there could be no better ally: the poet was to champion various writers including Aldous Huxley and Wilfred Owen. Neither was she afraid of making enemies or conducting media skirmishes with them, the most prominent among these being an ongoing feud with Noel Coward.

Sitwell dedicated her life to both the study and the writing of poetry. Her challenging formalist experiments and obscure style were often written off as attention-seeking, despite evidence to the contrary. Most famous was Façade, her spoken word collaboration with the composer William Walton. These readings would involve Edith sounding her poems out through a megaphone while sitting behind a curtain as the music played.

Seminal Moments

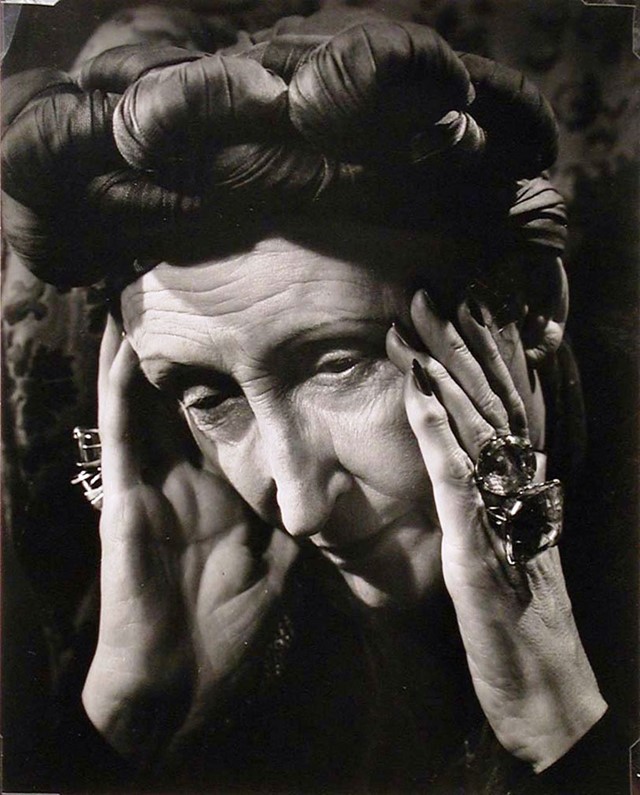

“I am not eccentric. It's just that I am more alive than most people. I am an unpopular electric eel set in a pond of goldfish.” Edith explained in Life magazine in 1963, a year before her death. Rather than attempting to assimilate the conventional, Sitwell instead charged with full speed in the opposite direction, wearing Plantagenet-style gowns, feather headdresses, brocade, antique jewellery and her famous rings. “She was considered an improbable and anachronistic fashion icon frequently photographed bristling with gigantic aquamarine rings – at least two to a finger, and plastered with vast brooches of semi-precious stones,” writes art historian Patricia Corbett. It is no surprise Sitwell came to be painted by Roger Fry, Pavel Tchelitchew and Wyndam Lewis, photographed by Cecil Beaton, sculpted by Maurice Lambert and fictionalised by D.H. Lawrence, to name but a few examples of her impact.

In 1953, headlines exploded with news that a peculiar English aristocrat had befriended a young film star. Edith had met Marilyn Monroe whilst visiting Hollywood where she was planning a film script. It was a relationship that many found surprising but Sitwell saw through the media’s misportrayal of Monroe, who was an avid reader and shared the poet’s love of modernism.

She is an AnOther Woman Because...

Following her death, Sitwell fell into ill repute. Her poetry stopped being read, which accounts for its continuing marginal status. Nonetheless, Edith Sitwell left an indelible mark on both the landscape of English Modernism and fashion's proclivity for accessorisation – and it is one that is only coming to be fully appreciated with time.