A confession. My knowledge of industrial noise music is zero. And yet when I met Yang Li and designer Federico Capalbo in Li’s studio (which is hidden behind an all-black Dickensian shopfront in the shadows of the Royal London Hospital), it became clear that they don’t so much know about it as live for it. They spoke with the fervour of love-struck teenagers, the unflinching, fierce dedication of disciples and, at times, in the foreign lexicon of the expert nerd. But here’s the kicker: it’s impossible not to be captivated.

Fashion might be his chosen medium but it’s the language of music Li slips into when describing his own oeuvre, likening the dichotomy between the done and the undone that’s central to his designs with the difference between live and recorded music. “When you go to a live gig it’s about the smell, the crowd, the heat; all those nuances flirt with your senses. The singer isn’t singing how you heard it on the record. It might be worse or better but that in whole immersive experience there’s lots of beautiful accidents. Injecting that spontaneous energy into designing clothes is my everyday mission,” he says. This is achieved by disrupting the design process – messing with something once it’s finished. He holds one of S/S17’s meticulously tailored jackets, that’s been cut and resewn at the back, aloft by way of example. “We really account for that happy mistake. If you’re rigid in sticking to a drawing, you are rigid”.

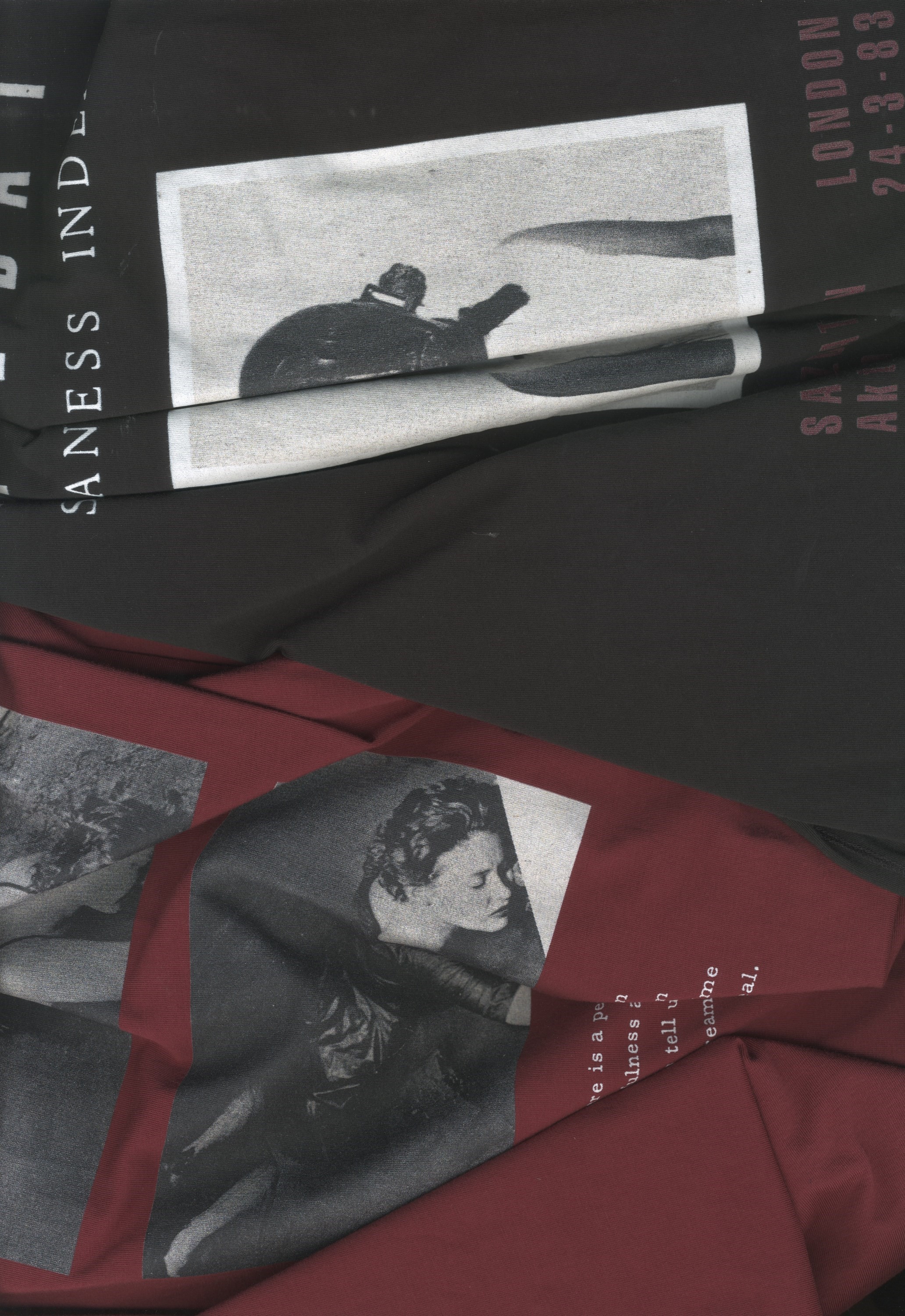

Li’s fluidity and his obsessive fanboy nature have come together in perfect harmony in his new project, Samizdat. A capsule collection of merchandise inspired by a fictional band, it’s heavily influenced by early 80s industrial acts like Ramleh, Maurizio Bianchi and Controlled Bleeding. The collection takes its name from the Russian word for “self-publish”, and its aesthetic has a bootleg-style rawness and comprises all the merch you’d find at any underground gig; think patches, lighters and tour tees.

What those band T-shirts represent is the perfect intersection between fashion and music, and the power of identifying with a certain tribe. Li likens wearing one to having a tattoo, holding a flag or wearing a football jersey. It’s declaring allegiance. “There’s a whole system of semiotics and behaviours in music, much more than other arts,” he observes.

Li describes being immersed in a “scene” as a bonding experience, adding that someone’s record collection is an avatar for themselves. It’s how he met and forged a collaborative relationship with Capalbo, with whom he’s working on the project. “It’s very small, very nerdy, very tight,” says Caplabo of the community. “When we go to gigs I feel safe somehow, there’s no bullshit, you are there because you really like the music – and this kind of music you really have to search for,” Li echoes. “People like us find a lot of strength from being different and being together.”

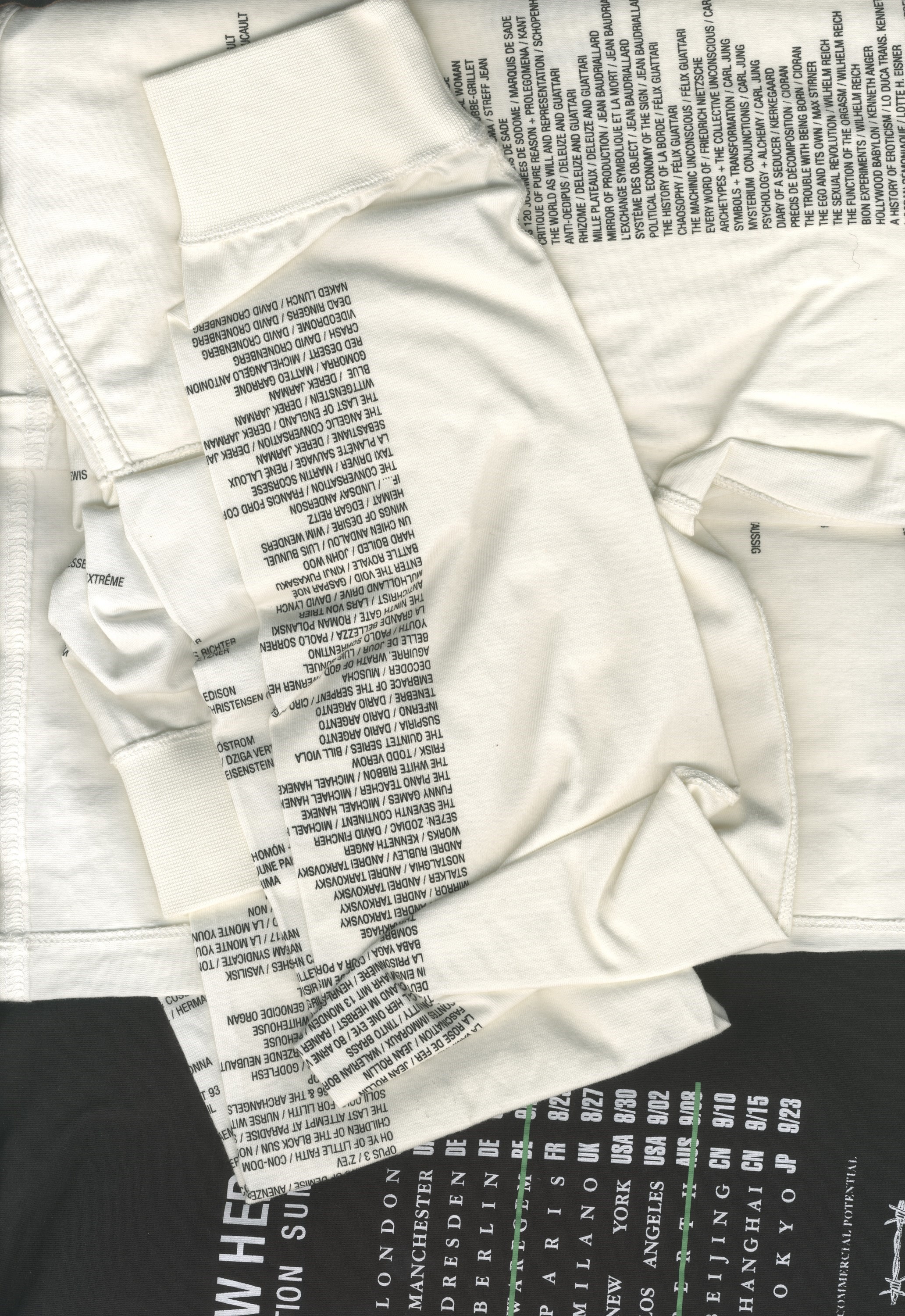

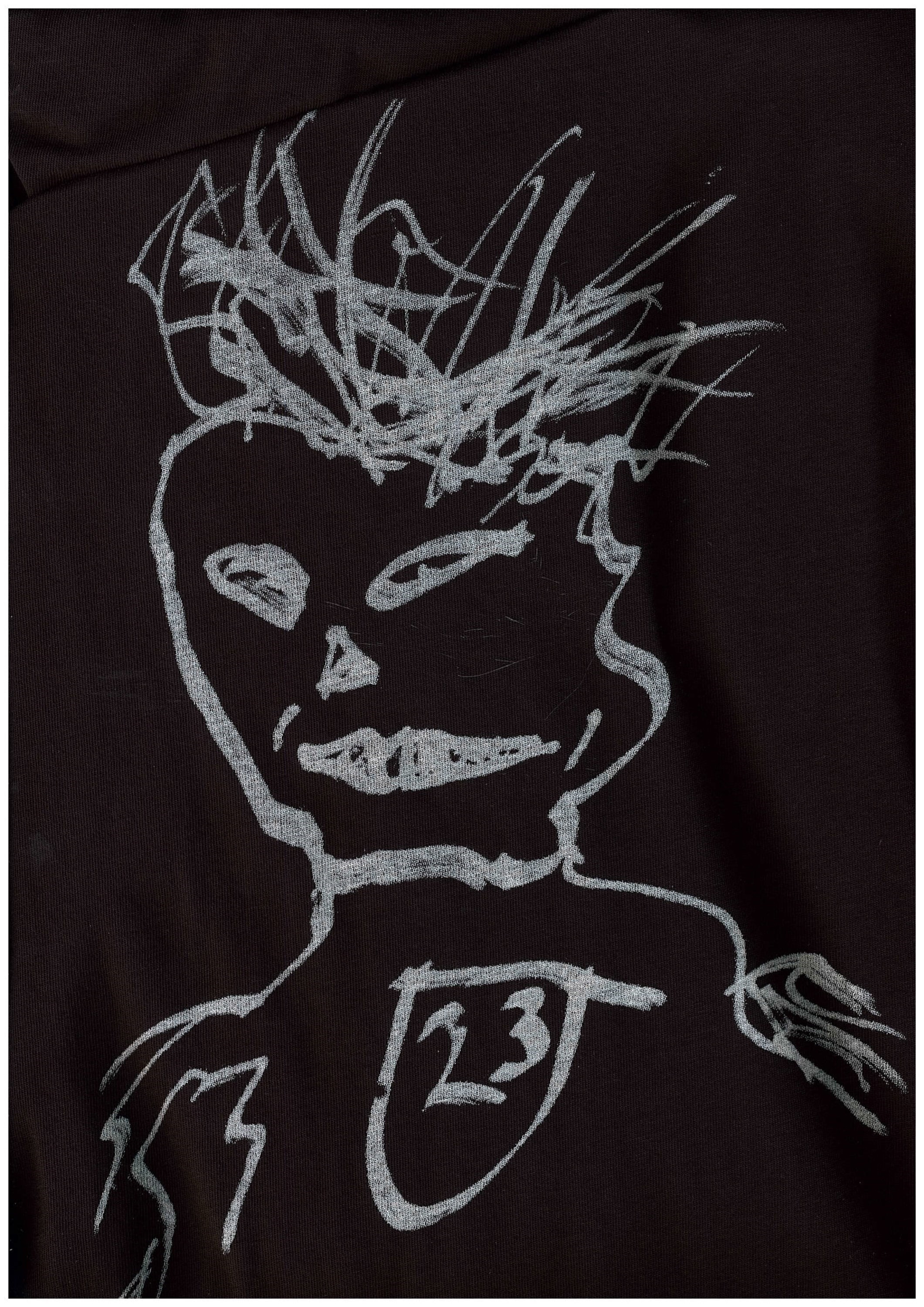

Samizdat as a band might be fictional, but the encyclopaedic references that go into the collection are very real. Indeed, it feels as much as a tribute to nerding out as it does to the particular genre of music. The meticulous attention to detail veers sharply into the obsessive, but it’s hard not to be charmed by the effusiveness and transparency with which Li and Capalbo decode and unpick the references. One T-shirt features a drawing of William Burroughs, “the godfather of counter culture”, another features a ‘fan’ drawing done on the rudimentary style computer programme that would have been used in the 80s. Nerdy in-jokes abound; logos are photocopied using the same (now hard to find) copier used to create the earliest zines and homemade logo T-shirts and – perhaps the nicest touch – even the T-shirt labels made to look like generic stock labels commonly used by bands. The attention to detail is impeccable.

That pernicious and subtle snobbery so often found in the world of the music is absent in the way the duo talks. You don’t need to ‘get’ all the references to appreciate it. For Li, there’s a joy in bringing this stuff to people who might not be industrial music aficionados. “Part of the pleasure of doing this is showing people something they may never see,” he explains, adding that his ‘reference’ T-shirt – which is a comprehensive bibliography of the books, films and bands inspiring him at the moment, from Michael Haneke films to Yukio Mishima’s Confessions of a Mask – is “the most valuable thing I made. It really is the heart and soul of the work”. That you might not know all the references doesn’t matter either. “Because today’s generation has an attention span of about five seconds, they might just look at it as a cool graphic but that’s fine, that’s part of the irony.”

The feeling of inclusivity continues into the collaborative nature of the project. Li is at pains to point out that although it falls under the mechanics of the Yang Li label, it’s not his project. Instead, he likens his role to one as the founder or editor of a magazine, drawing on contributors to create a rounded, fully formed thing. “It started with making clothes,” he says. “But the idea is we use it as a platform to work with others.” This means working with artists (cult illustrator Keiichi Ohta is on board for the second season, which imagines the band on tour in Japan) and expanding world of Samizdat to actually include music – a flipping of the script and rounding of the circle in one swipe. A Samizdat Soundcloud, with previously unreleased work by James Ginzburg of Emptyset, launches this week and the aim is, eventually, to put on a mini festival. It’s about breaking free of the established, formal channels of the creative industries in much the same way, say, producing a zine, writing fan fiction or uploading your own Tumblr is.

Maybe you’re not fluent in the language of industrial music either – Li and Capalbo are the first to acknowledge it’s niche – but there’s an unmissable charm in the enthusiasm they both exhibit. The tagline to Samizdat is “no commercial potential”. There’s a not-so hidden compliment in there. “We’ve been to gigs with ten people, three of them are the artist’s friends,” says Li. “And they’re still gunning it out as hard as someone earning £10 million a year because they do it for the love. We’re doing it for ourselves to make something exist which we like – and that’s it”.